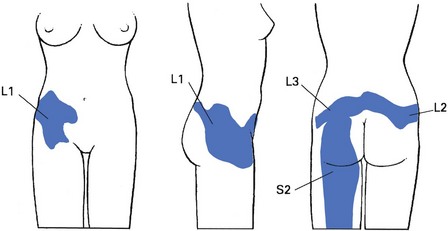

45 Pain felt in the hip and buttock does not necessarily originate from a lesion in these areas. Cyriax stated that most pain in the buttock derived from the lumbar spine (reference from L1 and S2), whereas pain in the thigh is referred from the lumbar spine and hip region as often as it has a local origin. When dealing with pain in this area, it is often not easy at first to determine if there is a problem in the lower back, the sacroiliac joint or the hip. Therefore, a detailed and chronologically ordered history is first taken, as described for the lumbar spine (see Ch. 36). Past and present symptoms are noted and the examiner is informed about the exact site and nature of the pain. Next, a preliminary examination must be performed that includes the whole lower quadrant: from the lumbar spine, over the sacroiliac and hip joints to the upper leg. Once it is clear that the symptoms do not arise from the lumbar spine or sacroiliac joint, the structures of the hip are examined more intensively. The first lumbar dermatome is represented by an area of skin at the outer and upper buttock which is partly overlapped by the second and third lumbar dermatomes (Fig. 45.1). The skin of the lower part of the buttock is derived from the first and second sacral segments. The fourth and fifth lumbar segments are not present in the buttock. In spite of this, fourth and fifth lumbar disc protrusions are the commonest cause of pain in the buttock,1 and are an expression of dural pain. The hip joint is formed largely from the third lumbar segment. Therefore pain referred from the joint may be felt in the upper and inner part of the buttock, and the inner aspect and front of the thigh and leg as far as the medial malleolus. Rarely, the joint has developed mainly from the fourth lumbar segment. In such cases, pain spreads along the outer side of the mid-thigh and leg, and may reach the big toe. Because referred pain does not always occupy the whole dermatome, it is possible for a hip lesion to refer pain to the knee only, perhaps also spreading along the front of the tibia.1,2 But pain felt only at the upper inner quadrant of the buttock strongly points to the low back or the sacroiliac joint. The sacroiliac joint normally gives rise to pain along the back of the thigh and calf. In rare instances, pain is felt in the groin as well (see p. 598). History taking is largely the same as in lumbar spine disorders (see Ch. 36) because it is not always clear from the onset if the patient has a lumbar, sacroiliac or hip problem. However, once it has become more or less apparent that the complaints are the outcome of a hip lesion, some particular questions should be asked. After the usual questions on the patient’s age, sex, occupation and hobbies, the examiner tries to find out what the actual problem is: pain, functional disability or instability? The problem should then be worked out systematically via a chronological approach: when and how did the problem start, what was its evolution and what are the current symptoms (Box 45.2)? • When did it start? Is it an acute, subacute or chronic problem? • What brought it on or how did it start? Was there an injury or did the pain appear without obvious reason? • How did it happen? In what position was the body and what forces were applied to the hip? • What were the immediate symptoms? Where was the pain? Was there any swelling? Was there any functional disablement? • What is the problem now? The examiner makes further enquiries about pain, pins and needles, instability or functional disability. • Where do you feel the pain (which dermatome)? As exact a description as possible must be obtained. • Do you have pain at rest or during the night? Nocturnal pain indicates a high degree of inflammation and may point to a serious disorder such as arthritis, haemarthrosis, tumour, metastasis or fracture. However, in an ordinary gluteal bursitis, lying on the affected side at night is also often painful. • What brings the pain on? Sitting, standing up, walking and running, climbing stairs, sitting or lying? If the pain starts after walking a certain distance, ask if it disappears after standing still for a while and reappears after walking the same distance: this suggests claudication in the buttock. • Does a particular movement provoke the pain? • Does the pain appear at the beginning, during or after some sort of exertion? • Do you have twinges, and when? This symptom is defined as a sudden, sharp and unexpected pain and is clearly indicative of momentary subluxation of a loose body. On walking, a severe twinge is felt shooting down the front of the thigh and the leg gives way at this point. • Is any movement accompanied by a click? Clicking may be indicative of loose bodies or acetabular labrum tears.3,4 • Does coughing hurt? This dural sign is highly suggestive of a lumbar intervertebral disc lesion but is also found in sacroiliac arthritis. • Do you have a feeling of instability?

Clinical examination of the hip and buttock

Introduction

Referred pain

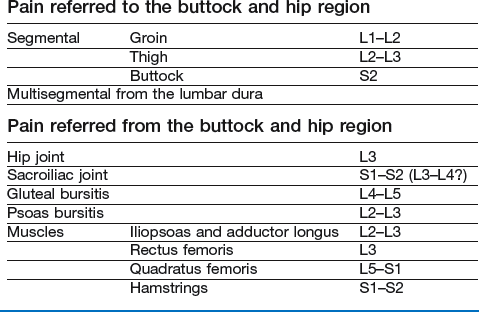

Pain referred to the buttock and hip region

Pain referred from the buttock and hip region

Hip joint

Sacroiliac joint

History

Onset

Current symptoms

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Clinical examination of the hip and buttock