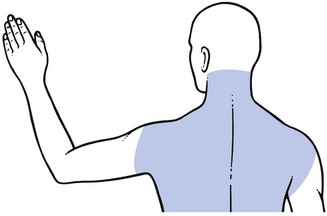

6 Next, the following questions are asked about the onset of the pain. The localization may change, either because the pain shifts to another place or because it spreads. Pain that spreads and gradually expands over a larger area is typical of an expanding lesion and should always arouse suspicion. On the other hand, pain that shifts from the scapular area to the upper limb is highly indicative of a shifting lesion (or disc lesion). The fragment of disc substance first displaces posterocentrally and compresses the dura mater, which results in central, bilateral or unilateral scapular pain; it then moves laterally and impinges on the dural investment of a nerve root. The scapular pain disappears and is replaced by a radicular pain down the upper limb. In order to interpret the distribution and evolution of the pain correctly, the mechanism of dural pain should be understood. Because the anterior aspect of the dura mater is innervated by a dense network of branches of sinuvertebral nerves originating at several levels, extrinsic compression and subsequent irritation of the dura may give rise to pain felt in several dermatomes. This phenomenon is called ‘multisegmental pain’ and is described in Chapter 1. Because the dural investment of the nerve root is only innervated from its own recurrent nerve, irritation here results in pain strictly felt in the corresponding dermatome, thus strict segmental pain. Also the duration of the pain is informative. Most benign cervical disorders are intermittent. If pain progressively worsens, then the presence of an irreversible lesion such as metastases must be borne in mind, particularly in the elderly. Root pain as the result of a disc protrusion lasts for a variable but limited period and then ceases as spontaneous remission takes place (see Ch. 8). Hence, root pain that lasts longer than 6 months should arouse suspicion of another, possibly progressive cause. Some types of headache can be recognized by paying attention to the history. Early morning headache in elderly patients is a typical example. The patient wakes every morning with headache and/or occipital pain. After some hours the symptoms ease and have completely disappeared by midday. Symptoms do not recur until the next morning. The sequence is repeated daily without fail and, as the years go by, pain tends to last longer into the day. This type of headache responds spectacularly to manipulative treatment (see p. 201). This is the most common pain reference for cervical lesions. The majority of pain in the trapezius or scapular area has a cervical origin, and must usually be considered as the multisegmental reference of a discodural conflict (Fig. 6.1). The pain may be unilateral, bilateral or interscapular. Depending on the patient’s age, it may be intermittent or constant; the older the patient, the more likely the pain will last over longer periods. Upper scapular pain or pain in the trapezius area may also have a C4 segmental origin. Other sources of trapezioscapular pain are a thoracic lesion, a local scapular lesion or a shoulder girdle problem. Paraesthesia is a very common symptom which may originate from any nerve fibre in the cervicoscapular area or in the arm (Table 6.1). Paraesthesia is often experienced as a ‘pins and needles’ sensation. In other instances, the patient may describe the feeling as ‘numbness’. The moment the patient mentions the presence of such symptoms, the examiner should carefully determine how proximal they are because, as has been explained in Chapter 2, the point of compression always lies proximal to that of the paraesthesia. The lesion may lie at any one of a number of different levels but the vaguer the distribution of the pins and needles, the more proximally the lesion needs to be sought. Table 6.1 Lesions of the brachial plexus at the thoracic outlet give rise to paraesthesia in one or both hands and affect all digits. When there is external pressure and because of the release phenomenon, pins and needles are only felt after the compression has ceased (see Ch. 2). They are often nocturnal, waking the patient after some hours’ sleep.

Clinical examination of the cervical spine

History

Pain

Onset

Pain of cervical origin very often starts at the cervical spine but frequently spreads or shifts to another region quite quickly, so that the cervical source may pass unnoticed.

Pain of cervical origin very often starts at the cervical spine but frequently spreads or shifts to another region quite quickly, so that the cervical source may pass unnoticed.

Interscapular onset of pain is typical of a lower cervical disc lesion that compresses the dura. In contrast, it is very unusual for pain to begin in the arm. Should this occur, the possibility of a neurofibroma, compressing a nerve root, has to be considered in young people. In the elderly, an osteophyte or even a malignant process is more probable.

Interscapular onset of pain is typical of a lower cervical disc lesion that compresses the dura. In contrast, it is very unusual for pain to begin in the arm. Should this occur, the possibility of a neurofibroma, compressing a nerve root, has to be considered in young people. In the elderly, an osteophyte or even a malignant process is more probable.

Pain of cervical origin may occur in discrete attacks, especially when a disc lesion is responsible. It is important to encourage the patient to recall the first episode and to ask for a chronological account. In discal root pain, a normal period of spontaneous relief should be recognizable.

Pain of cervical origin may occur in discrete attacks, especially when a disc lesion is responsible. It is important to encourage the patient to recall the first episode and to ask for a chronological account. In discal root pain, a normal period of spontaneous relief should be recognizable.

Evolution

Current pain

Localization

Headache

Pain in the trapezioscapular area

Paraesthesia

Level

Cause/site of cause

Symptoms

Cervical

Myelopathy:

No pain

Intrinsic

Multisegmental paraesthesia on neck flexion

Extrinsic

Lhermitte’s sign

Nerve root

Pain

Segmental paraesthesia

Compression phenomenon

Shoulder girdle

Brachial plexus

Vague paraesthesia

Release phenomenon

Arm

Nerve trunk

Defined area of paraesthesia

Specific tests

Nerve ending

Cutaneous analgesia

(Paraesthesia)

At the shoulder girdle

Clinical examination of the cervical spine