CHAPTER 4 Clinical Evaluation of Shoulder Problems

From our first days in medical school, we are taught that establishing a correct diagnosis depends on obtaining a meaningful and detailed medical history from the patient. This requires the physician to ask specific questions while at the same time actively listening to the responses from the patient. Often physicians formulate their next question without listening to and interpreting the answer to the previous inquiry. Obtaining a good patient history is, in itself, an art that requires experience and patience. I vividly recall one of my mentors stating that all patients come to your office and tell you exactly what is wrong with them when they answer but four or five questions. Our task is to decipher their answers to those few questions.

PATIENT HISTORY

Recall that many widely varying diagnoses manifest with similar symptoms and only after a complete history and examination can differentiation of diagnoses be made. For example, if a patient presents complaining of an inability to elevate or externally rotate the arm, the physician might immediately diagnose a frozen shoulder. Sending that patient, who really has advanced osteoarthritis, to physical therapy to increase the range of motion (ROM) ensures a therapeutic failure. A diagnosis is only established after each phase of the evaluation is complete. Anything else in the name of expedience and efficiency does a disservice to our patients.

Sex

Female patients also tend to present in far greater numbers than males with adhesive capsulitis1 This is in contrast to the idiopathic stiff and painful frozen shoulder, which is equally prevalent among male and female patients and describes restricted shoulder ROM associated with pain. A frozen shoulder can result from any number of pathologic processes such as post-traumatic stiffness, immobilization, and tendinitis. Adhesive capsulitis is a specific diagnosis most prevalent in women 40 to 60 years of age. It is associated with an idiopathic inflammatory process involving the glenohumeral joint capsule and synovium that results in capsular contraction and adhesion formation.

Presenting Complaint

When the physician inquires about a patient’s chief complaint during the initial visit, the response is most commonly one of pain. Subsequent questioning is directed toward better understanding the characteristics of that pain; a presumptive diagnosis will follow from this. Most presenting complaints related to the shoulder are defined by patients as pain, stiffness, loss of smooth motion, instability, neurologic symptoms, or combinations of these.

Pain

Onset of the Pain

Radicular pain of cervical origin likely has an insidious onset. Patients might acknowledge that turning the head provokes symptoms. Arm pain while driving is often a tip-off to pain of a cervical origin. Pain described as sharp and stabbing and occurring intermittently in the scapular muscles and around the top of the shoulder nearly always finds its source in the cervical spine.

Factors That Alleviate Pain

In the same way that analysis of aggravating factors provides insight into the etiology of the shoulder problem, so too does inquiry into those features and factors that alleviate or improve the symptoms. Many times the alleviating factor provides the best information in arriving at the correct diagnosis. Whereas there is much overlap in diagnoses with respect to aggravating factors, it would be unusual to find one factor that solves several different problems. For example, if a patient finds that an over-the-counter antiinflammatory truly improves the symptoms, it would logically follow that the patient has an inflammatory condition. Certainly an antiinflammatory does not solve the apprehension of a shoulder instability problem, nor would it likely manage the pain of an acute fracture. Patients with a frozen shoulder characteristically state that there is absolutely no improvement in their pain with nonsteroidal antiinflammatories.

Patients with rotator cuff tears and impingement often note that in placing the affected arm over their head, they find significant improvement in their pain. Often this arm position is the only way they can find meaningful sleep. This is called the Saha position (Fig. 4-1), named for the Indian orthopaedic surgeon who recognized this phenomenon. He postulated that with the arm resting overhead, there is a balance of tension of the cuff muscles in their least tense state. When the arm is passively elevated overhead in the supine patient, the supraspinatus is subject to its least tension, and pain diminishes in many patients.

The response to local anesthetic injections when placed in specific anatomic locations around the shoulder can be very instructive and diagnostic. In a patient with chronic subacromial impingement, 5 mL of 1% lidocaine placed in the subacromial space provides immediate and dramatic relief of pain (Fig. 4-2). This response becomes diagnostic of a subacromial process, and it becomes especially valuable when trying to discern whether the patient’s perceived pain is originating in the shoulder or whether it is referred pain from the neck. A similar local injection test is useful in evaluating the acromioclavicular joint as a source of the patient’s pain. Alleviation of pain with arm adduction following an injection directly into the acromioclavicular joint strongly suggests pathology at this joint. Intra-articular injections can provide similar supporting information regarding the source of a patient’s symptoms.

Response of Symptoms to Self-Prescribed Treatment

It is important to take time to explore what methods, medications, and modalities the patient might have tried before coming to the physician. Explore the realm of nutraceuticals and ask specifically about the common ones, including glucosamine, chondroitin, shark carti-lage, and methylsulfonylmethane (MSM), because many patients do not consider these to be medicines and do not include them in their medication lists. Patients consume seemingly countless vitamins and vitamin combinations in their effort to improve their physical well-being. With the exception of glucosamine and chondroitin, which themselves have not been subjected to the rigors of the scientific method to prove their efficacy, there is little published objective information to make recommendations to patients. Nevertheless, we have all seen patients who are certain that some combination of these herbs, vitamins, and supplements have affected their medical condition in some way or another. It is important to query and document these treatments in the overall evaluation of the patient with a shoulder problem.

Box 4-1 lists the facets of pain that need to be explored during a patient history.

BOX 4-1 Aspects of Pain to Be Evaluated

Character (dull, sharp, ache, lancinating)

Onset (acute, chronic, insidious, defining moment)

Location (e.g., superior, posterior, anterior)

Patterns of radiation (neck, arm, below elbow, deltoid insertion)

Aggravating factors (e.g., arm position, time of day)

Alleviating factors (e.g., arm position, medications)

Instability

Isolated symptomatic posterior shoulder instability is most often associated with a very specific event or process. Although falling on the outstretched arm is a common scenario, because the arm is most often placed in the scapular plane to brace the fall and protect the head, a posterior force is only placed on the hand. As the body continues to fall to the ground, the arm is extended at the shoulder, placing an anterior force on the shoulder. This results in the much more common anterior dislocation under such circumstances; posterior shoulder dislocations are rarely associated with traumatic events that include falls.

Box 4-2 lists the queries that should accompany a history that suggests instability.

Box 4-2 History Related to Instability

Nature of onset (traumatic or atraumatic)

Perceived direction (anterior, posterior, inferior, or combination)

Degree (subluxation or dislocation)

Method of reduction (spontaneous or manipulative)

Character of symptoms (apprehension, pain, paresthesias)

Frequency (daily or intermittently)

Volition (voluntary, involuntary, obligatory)

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Cervical Spine (Neck)

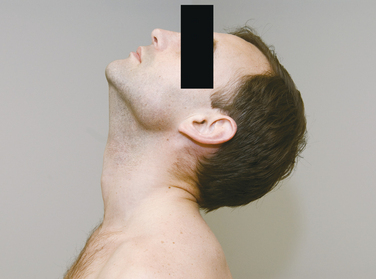

Neck extension (Fig. 4-3) is recorded by noting that the imaginary line from the occiput to the mentum of the chin extends beyond the horizontal. Flexion is recorded by noting how many fingerbreadths the chin is from the chest when the patient flexes the neck as much as possible (Fig. 4-4). The patient leans the head to the side while looking forward (Fig. 4-5), and the distance from the shoulder to the ear is recorded for lateral flexion. Lastly, the patient turns the head from side to side and the examiner notes the degree of rotation. These cervical spine motions are made actively (by the patient) rather than passively (by the examiner).

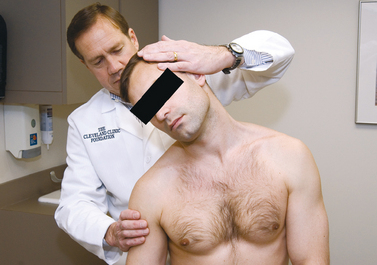

The Spurling test (Fig. 4-6) is performed by placing the cervical spine in extension and rotating the head toward the affected shoulder. An axial load is then placed on the spine. Reproduction of the patient’s shoulder or arm pain is considered a positive response.

Although a detailed neurologic examination is beyond the purview of most shoulder examinations, clinical judgment determines the degree of peripheral nerve assessment necessary to establish a correct and complete diagnosis. Examining the strength of the trapezius, deltoid, spinati, and biceps and triceps muscles suffices for most general shoulder examinations. However, in some situations a more thorough examination needs to be completed, which includes assessment of motor and sensory distributions of each peripheral nerve of the upper extremity or extremities.

Shoulder

Inspection

Inspection of both shoulders can reveal pathology that would otherwise go unnoticed if the examiner relied solely on the patient history or physical examination. Both shoulders need to be exposed (Fig. 4-7). First, observe the clavicles for deformity at both the sternoclavicular joint and acromioclavicular joint. A prominent sternoclavicular joint can be due to an anterior dislocation, inflammation of the synovium, osteoarthritis, infection, or condensing osteitis. A loss of sternoclavicular joint contour is consistent with a posterior dislocation of the medial clavicle, which is worked up urgently to confirm the diagnosis. The acromioclavicular joint is often prominent secondary to osteoarthritis and needs to be compared to the opposite side for symmetry.

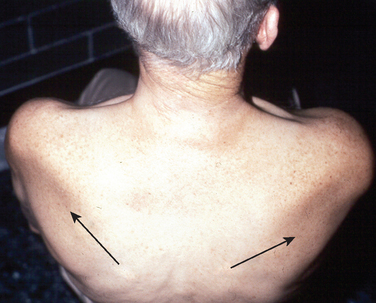

Muscle inspection begins with the three portions of the deltoid muscle. Marked atrophy is easy to identify, but deficiencies in the posterior or middle deltoid are more difficult to appreciate until active shoulder motion is initiated (Fig. 4-8). In patients with a large amount of subcutaneous tissue, palpation of the muscle belly may be the only way to distinguish a pathologic muscle contraction from the normal side. Inspection from the back reveals the muscle bulk of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles, as well as the trapezius muscle (Fig. 4-9).

Once the muscle bulk has been assessed, the static position of the scapulae must be noted. If the soft tissue obscures the view of the medial border or the scapular spine, palpation of these landmarks can help visualize the attitude of the scapula at rest. Excessive lateral rotation of the scapula or an increased distance between the medial border of the scapula and the spine could be caused by trapezius palsy. This can also be accompanied by a prominent inferior tip of the scapula. A laterally prominent inferior scapula tip can be caused by serratus anterior muscle weakness related to a long thoracic nerve injury, but this might only be recognized during active shoulder motion.

The most common skin manifestations of shoulder pathology are ecchymosis, which occurs after fractures, dislocations, or traumatic tendon ruptures, and erythema, which occurs with infection and systemic inflammatory conditions. Less commonly, the skin around the anterior shoulder is swollen and enlarged due to a subacromial effusion and a chronic rotator cuff tear (Fig. 4-10). The examiner notes the presence of scars and their location and character. A widened scar can indicate a collagenopathy often seen in association with shoulder instability.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree