Clavicle Fractures

CASE PRESENTATION

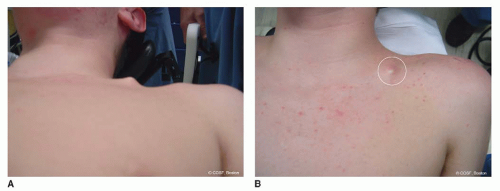

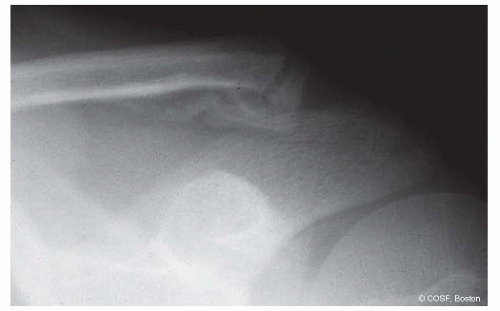

A 16-year-old female presents for management of an isolated right clavicle fracture 3 days after a collision with an opponent in a soccer game (Figure 25-1). She has been treated in a sling and swathe for immobilization since her initial evaluation in an emergency care setting. The fracture is closed, but there is mild tenting of the skin superior and anterior to the mid-diaphysis of the clavicle by a palpable fracture fragment. Capillary refill is intact over that fragment, and the skin is not blanched. The distal neurovascular status is intact to the ipsilateral arm and hand.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

What are the mechanisms of injury for neonatal, pediatric, and adolescent clavicle fractures?

What are the associated injuries with a clavicle fracture?

What is the expected outcome from nonoperative treatment of a clavicle fracture?

Is there a difference in outcome between sling and figure-of-eight immobilization treatment for clavicle fractures?

What are the indications for operative treatment of a clavicle fracture?

Is there a difference in results between nonoperative and operative methods?

Is there a difference in outcome and/or complication rates from internal fixation with K-wires, intramedullary elastic nails, intramedullary screws, or plate and screw fixation?

What are the complications from clavicle fractures and the various methods of treatment?

How are nonunions of the clavicle treated?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

Etiology and Epidemiology

The clavicle is an S-shaped bone that articulates medially with the sternum and laterally with the acromial extension of the scapula. The clavicle serves as the origin for the pectoralis major and deltoid muscles along with the insertion of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. The sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) and acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) ligaments insert proximally and distally on the clavicle, respectively. The motions of the clavicle include protraction and retraction, and rotation and elevation during shoulder abduction. The brachial plexus, subclavian vessels, and apex of the lung lie beneath the clavicle and are at risk for injury with a displaced clavicle fracture. The clavicle is predominately subcutaneous and susceptible to injury with a direct blow (less common) or lateral compression trauma (most frequent).

Clavicle fractures are common in children and adolescents. Birth fractures occur in 1% to 2% of all vaginal deliveries, most often with large-for-gestational-age infants and during extraction and difficult deliveries.1, 2 and 3 Childhood injuries resulting from a fall include those involving bicycles, playground equipment, and sports. Adolescent injuries usually involve contact sports. Motor vehicle accidents account for many of the clavicle fractures associated with polytrauma.4 Rare stress fractures of the clavicle have occurred in rowers, gymnasts, and other athletes involved in repetitive, high-intensity training sports.5

Clinical Evaluation

Clavicle fractures are almost always associated with pain. In the neonates, their discomfort can be mild, especially with stable fractures, and thus misinterpreted as hygiene

or hunger complaints. At times, this will result in a delay of proper diagnosis until there is palpable callus at 5 to 21 days. The most common associated diagnosis with a neonatal clavicle fracture is a brachial plexus injury. The flail limb in these children can be either a pseudoparalysis from an unstable fracture or a combination nerve and skeletal injury. If limited motion persists when the fracture heals or obvious signs of a severe nerve injury are seen immediately after birth (Horner syndrome, flail hand, elevated hemidiaphragm), appropriate care for a brachial plexus palsy is warranted (see Chapter 20).

or hunger complaints. At times, this will result in a delay of proper diagnosis until there is palpable callus at 5 to 21 days. The most common associated diagnosis with a neonatal clavicle fracture is a brachial plexus injury. The flail limb in these children can be either a pseudoparalysis from an unstable fracture or a combination nerve and skeletal injury. If limited motion persists when the fracture heals or obvious signs of a severe nerve injury are seen immediately after birth (Horner syndrome, flail hand, elevated hemidiaphragm), appropriate care for a brachial plexus palsy is warranted (see Chapter 20).

FIGURE 25-1 Preoperative radiograph of segmental right clavicle fracture with pending skin compromise (arrow). |

In an infant and young child, the differential diagnosis includes nontraumatic disorders such as infantile cortical hyperostosis, congenital pseudarthrosis (see Chapter 18), cleidocranial dysplasia, and short clavicle syndrome. In older children and adolescents, the differential includes neurofibromatosis and clavicular pseudarthrosis, Friedrich disease, hypertrophic osteitis, chronic multifocal periostitis and osteomyelitis, and SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis).6

Pediatric and adolescent fractures are classified by location and fracture pattern. Simply, the fractures are (1) medial fractures and SCJ dislocations (see Chapter 24), (2) diaphyseal, and (3) lateral (distal) fractures and ACJ joint dislocations. The most common injury is in the middle third (75% to 85%) (sternocleidomastoid muscle insertion to coracoclavicular ligament insertion) followed by distal third (10% to 20%). The fractures can be subclassified as two-part, segmental, or comminuted; open or closed; and nondisplaced or displaced. The more complex the fracture pattern, the more risk of associated injuries, nonunion or malunion, and need for operative intervention.

Lateral or distal clavicle fracture dislocations at the ACJ in children and adolescents were classified by Dameron and Rockwood as a modification of the adult ACJ separation classification system. Defining the injuries to the periosteum, acromioclavicular (AC), and coracoclavicular ligaments and assessing the direction of clavicular displacement determines the classification type. The coracoclavicular ligaments remain attached to the periosteum, and the clavicle bone remains intact but displaces out of the periosteal sleeve. Type I is nondisplaced; type II is a partial tear of the AC ligaments and lateral periosteum with some instability of the clavicle; in type III the clavicle is displaced superiorly (25% to 100% width of clavicle) with complete tear of AC ligaments and superolateral periosteum; with type IV the clavicle displaces posteriorly and gets entrapped in the trapezius muscle; type V is completely displaced (>100%) superiorly into the subcutaneous tissues; and type VI is displaced inferiorly beneath the coracoid. Distal clavicle fractures are further divided into nondisplaced or minimally displaced (type I); fractures medial to coracoclavicular ligament (type II); and intra-articular fractures (type III). Displaced intra-articular fractures are problematic.

More severe injuries can include a floating shoulder with damage to the clavicle and the scapula.7, 8 and 9 This situation involves disruption of the superior shoulder suspensory complex and potentially an unstable shoulder girdle. Operative treatment of both fractures, one fracture, or neither has been advocated. Stabilization of unstable, displaced fractures is appropriate. Floating shoulder injuries are rare in children but should not be missed due to concern about associated injuries to the chest and intrathoracic organs. Similarly, there are reports of associated C1-C2 rotatory displacement with clavicle fractures. Finally pathologic fractures, such as postirradiation treatment, can occur and require a different and often more aggressive treatment protocol for successful healing.10

Surgical Indications

They want some clarity. We just don’t have answers for them.

—Ted Ludwig

The mainstay for treatment of midshaft and lateral clavicle fractures is immobilization and biologic healing in situ. Nonoperative treatment is indicated in the majority of middle and distal clavicle fractures. However, like many other pediatric and adolescent fractures, clavicle fracture treatment in the young, especially the athletic adolescent, is influenced by operative techniques and internal fixation outcomes in the adult.11, 12, 13, 14 and 15

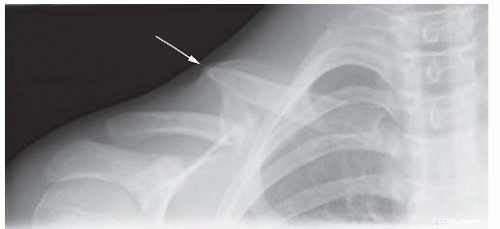

The indications for open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) of clavicle fractures in children are changing as we write. Clear indications for surgery include (1) open fractures, (2) displaced fractures with skin compromise (Figure 25-2) or neurovascular impairment, and (3), for most surgeons including us, type III, IV, and V lateral clavicle fracture dislocations. Evolving indications in many centers (including ours) for ORIF now include (1) displaced segmental and comminuted diaphyseal fractures in the adolescent (Figure 25-1), (2) polytrauma patients with displaced fractures, and (3) (less often) diaphyseal fractures with >2 cm of overlap in the older adolescent. The adult patients with the greatest initial fracture displacement had the most long-term complaints in terms of overhead strength and endurance.13,16,17 Polytrauma patients with displaced clavicle fractures had lower outcome scores.18 The risk of nonunion is higher when a lack of cortical contact and/or comminution exists between fracture fragments.19

All of the reasons noted above make ORIF of certain clavicular fractures in specific clinical situations and pediatric patients appropriate.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

• Nonoperative Treatment

Nonoperative treatment of a nondisplaced or minimally displaced (<1 to 2 cm) fracture is indicated and will result in a 95% to 98% union rate and positive outcome20,21

(Figure 25-3). Comparative results indicate that both a sling and a figure-of-eight dressing are equivalent. There is even some evidence that follow-up care is not necessary in these children, though we tend to follow them until full healing of bone and soft tissues is apparent.22

(Figure 25-3). Comparative results indicate that both a sling and a figure-of-eight dressing are equivalent. There is even some evidence that follow-up care is not necessary in these children, though we tend to follow them until full healing of bone and soft tissues is apparent.22

Radiographic healing occurs over the course of 4 to 12 weeks depending on the fracture pattern, age, and overall health of the patient. Palpable callus is present early (7 to 14 days) and coincides with decreased pain and self-protection. Restoration of motion and strength occurs readily in these stable fractures. Protection against refracture (∽2%) is important until there is full bony healing, motion, and strength.

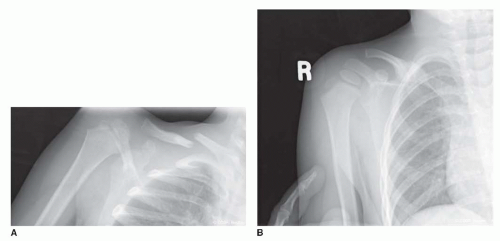

FIGURE 25-3 A: Moderately displaced fracture treated with sling immobilization. B: Healed fracture with radiographic evidence of palpable callus on clinical exam. |

Types I, II, and III lateral clavicle fractures can be treated closed. The torn periosteum will heal (Figure 25-4), and even the mild-to-moderate displaced fractures will remodel. There are times where a distal “double barrel” clavicle will appear before the old superior clavicle resorbs as the new inferior clavicle forms in the periosteal sleeve. This can even occur in type V clavicle fractures if the patient is young enough and the family and surgeon can wait long enough. As with diaphyseal fractures, short-term immobilization for up to 3 to 4 weeks is followed by restoration of motion and strength before return to full activities.

• Exostosis Excision

Of the displaced fractures treated nonoperatively, some will heal with a symptomatic malunion. There will be a palpable exostosis, and the patients will complain of pain with direct contact (backpacks, sporting equipment). There may be loss of endurance and strength with overhead activities. Surgical treatment is either by corrective osteotomy or by exostosis excision. For the patients in whom there is normal strength, motion, and endurance but pain with direct pressure, exostosis excision is indicated.23

A modified beach chair position is utilized with prepping and draping of the involved arm and entire shoulder girdle to the SCJ. An incision in the skin lines is made directly over the clavicular malunion. Dissection is carried down to the exostosis while identifying and protecting the cutaneous nerves as they cross the clavicle from superior to inferior. The nerves descend deep into the platysma layer and often course with more easily identified veins. Cutting these nerves will cause a symptomatic neuroma. Subperiosteal dissection is performed, and the exostosis is isolated. With a rongeur and osteotomes, the exostosis is excised and the bone contoured to smooth surfaces. Rasping of the bone may be necessary. Bone wax is applied, and the wound is closed in layers, including periosteum, platysma, subcutaneous, and skin layers. Since we are trading a symptomatic bump for a scar, the aesthetics of the closure matter. Sling protection and restriction of activities are utilized until the risk of refracture is minimal.

▪ ORIF Displaced Diaphyseal Clavicle Fractures

Plate and Screw Fixation

The will to win is important, but the will to prepare is vital.

—Joe Paterno

An ORIF approach to segmental, comminuted, open and markedly displaced fractures is more commonplace now than an orthopaedic generation ago. Fixation methods of diaphyseal fractures include plate and screws (locked and nonlocked, standard and precontoured),24, 25 and 26 elastic nails,27, 28 and 29 intramedullary screws,30

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree