Chronic Lateral Ankle Instability

Markus Walther

DEFINITION

Lateral ligament injuries of the ankle are treated conservatively with good results in most cases. However, several factors may lead to chronic ankle instability with recurring ankle sprains:

Inadequate primary treatment

Incomplete healing of the ligaments

Repetitive trauma with deteriorated tissue quality

Patients with chronic ankle instability can be divided into two groups:

Patients with sufficient tissue quality to perform a local repair

Patients with inadequate tissue quality for a local repair

A Brostrom procedure for lateral ankle reconstruction is possible as long as there is sufficient tissue.

In patients with insufficient local tissue, an augmentation is needed to rebuild or reinforce the lateral ligaments. There are different options of tendon grafts, each with certain advantages and disadvantages:

Tenodesis

Semitendinosus tendon or gracilis tendon

Plantaris longus tendon

Another surgical option is the augmentation of the ligaments with fibular periosteal flap.2

ANATOMY

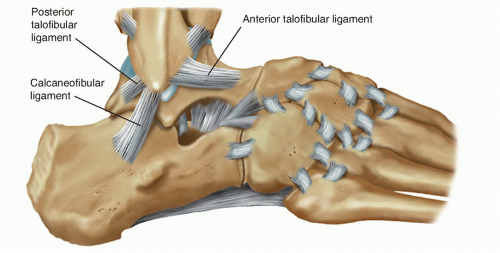

Laterally, the ankle is stabilized by the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL), and the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) (FIG 1).6

Additional stability is provided by the bony structures. Especially in dorsal extension, the talus is locked between the medial and lateral malleolus.

PATHOGENESIS

Torn lateral ligaments are the result of an ankle sprain. Depending on the severity of the sprain, one to three of the lateral ligaments are injured. A rupture of the ATFL is involved in most cases.

Anatomic classification

Grade I: ATFL sprain

Grade II: ATFL and CFL sprain

Grade III: ATFL, CFL, and PTFL sprain

American Medical Association (AMA) standard nomenclature system by severity

Grade I: ligament stretched

Grade II: ligament partially torn

Grade III: ligament completely torn

Grading by clinical presentation symptoms

Mild sprain: minimal functional loss, no limp, minimal or no swelling, point tenderness, pain with reproduction of mechanism of injury

Moderate sprain: moderate functional loss, unable to toe rise or hop on injured ankle, limp when walking, localized swelling, point tenderness

Severe sprain: diffuse tenderness and swelling, crutches preferred by patient for ambulation

With each ankle sprain, proprioception of the ankle joint is compromised.

The risk for another ankle sprain increases after each injury. In an uninjured person, an ankle sprain will occur in 1:1,000,000 steps. This risk increases to 1:1000 steps after a severe ankle sprain.13

Chronic ankle instability is the combination of insufficient active and ligament stabilization mechanisms.

There is some evidence that special anatomic variations increase the risk of developing chronic ankle instability after an injury.15

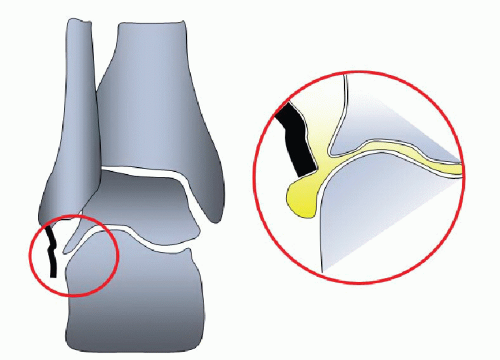

The healing of the ligaments can be compromised by synovial fluid between ligament and bone (FIG 2).

NATURAL HISTORY

Chronic instability is a risk factor for degenerative arthritis of the ankle joint. Valderrabano et al22 have shown an increased prevalence of arthritis in patients with chronic ankle instability.

Recurrent ankle sprains are likely in the future, but this is strongly dependent on lifestyle and sports activities.23

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The patient history includes sustained injuries, frequency of ankle sprains, and causes of pain as well as restrictions in daily living and sports.

The degree of disability experienced by the patient depends on the degree of instability and the physical demands.

Many tests for ankle instability are strongly dependent on patient cooperation. If positive, however, they can be highly specific.

The examiner should check the range of motion of the ankle joint with a stretched and a bent knee to rule out a shortening of the gastrocnemius or soleus muscle (or both). Restricted dorsiflexion with a stretched knee joint that is not found with a flexed knee is specific for a shortening of the gastrocnemius muscle (Silfverskiöld test).

The inversion test is used to assess for a ruptured CFL.

Medial ankle stability is checked in a plantarflexed position of the ankle to avoid a locking of the talus in the joint, which can mimic ligamentous stability. If positive, it is highly specific for a ruptured deltoid ligament.

Insufficiency of the fibulocalcaneus ligament often affects the stability of the subtalar joint. The stability is checked in dorsiflexion of the ankle to lock the talus in the upper ankle joint. If positive, it is highly specific for a ruptured CFL in combination with subtalar instability.16

Effusion can be palpated ventrally, but smaller amounts of fluid are difficult to detect.

The ankle drawer test strains the ATFL and is highly specific for rupture of this ligament.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs should be obtained to evaluate potential bony pathology.

Stress radiographs: The anteroposterior (AP) view shows the lateral opening of the joint. An anterior talar shift can be seen on the lateral stress view (FIG 3).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) gives valuable information on the lateral ligaments and other pathology. In chronic instability scarring, effusion and synovitis war often found. However, it is impossible to judge functional stability in an MRI. Frequent additional pathologies visible on MRI are tears of the peroneal tendons, osteochondral lesions, and bone edema.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Articular injury (chondral or osteochondral fractures)

Nerve injuries (sural, superficial peroneal, posterior tibial)

Tendon injury (peroneal tendon tear or dislocation, tibialis posterior)

Other ligamentous injuries (syndesmosis, subtalar, bifurcate, calcaneocuboid)

Impingement (anterior osteophyte, anteroinferior tibiofibular ligament, scars)

Unrelated pathology, masked by routine sprain (undetected rheumatoid condition, diabetic neuroarthropathy, tumor)

Lateral ankle instability with hindfoot varus deformity21

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

The goals of nonoperative treatment are improving proprioception and strength. This can be achieved by physiotherapy and exercises.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree