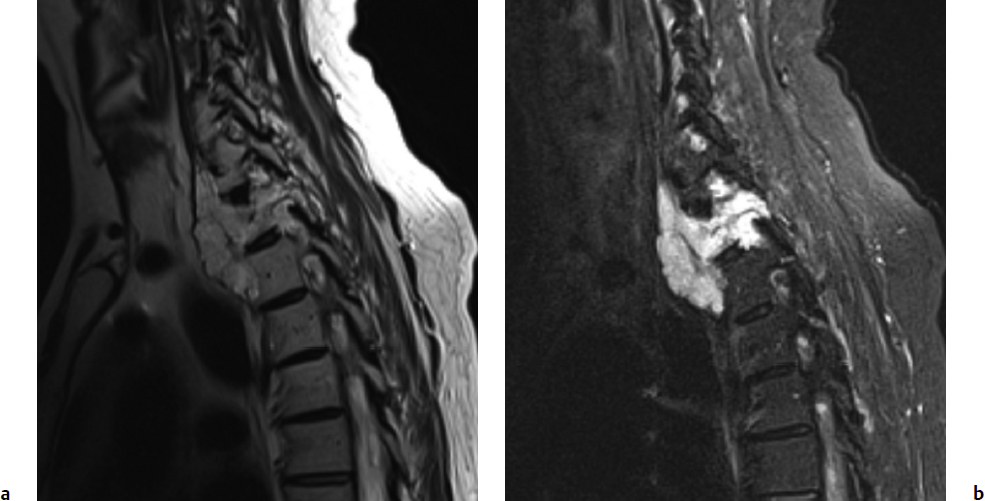

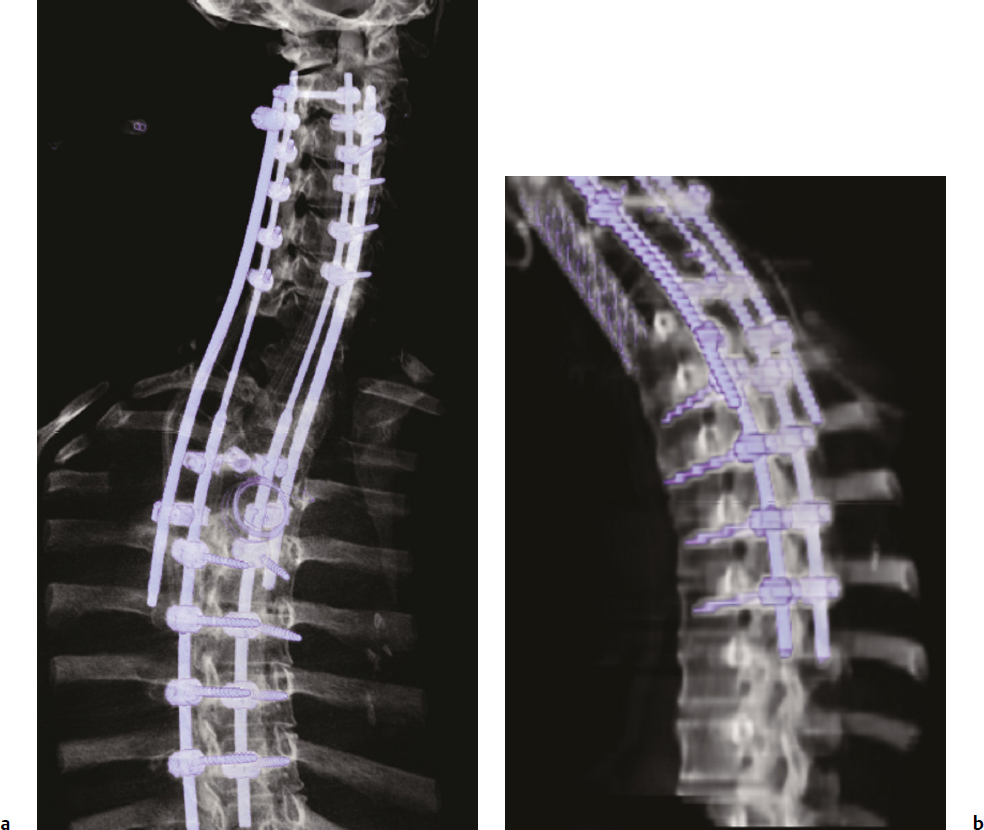

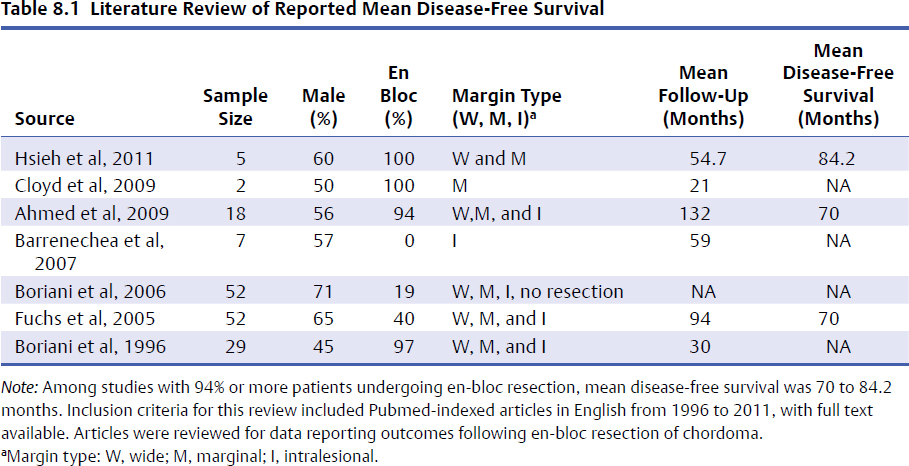

8 Chordomas are a rare, benign tumor arising from remnant notochordal cells. These lesions occur most commonly in the clivus and sacral spine, at the embryological end points of the notochord. Chordomas are most often locally invasive and aggressive; however, metastases to the lungs and other sites are not uncommon. Further, tumors in the sacral spine may grow to large sizes within the pelvis and abdomen, disrupting the bowel and bladder, and motor and sexual function. Although some drug therapies are under investigation, chordomas are classically resistant to chemotherapy and conventional radiation, and en-bloc surgical excision or gross total resection with subsequent radiotherapy offers the best outcomes for patients.1–4 Chordomas occur most frequently in middle-aged men. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, which reviewed the outcomes of 414 chordoma patients, the average patient age is 59.9 years, with a slight majority (62.8%) of patients being male.5 Chordomas are rare in the pediatric population. Classically, patients with local disease do well after surgery, with a median survival of 75 months reported in recent literature.5,6 Patients with metastatic disease have significantly decreased survival (median 24 months), compared to a prolonged median survival for primary spinal chordoma patients.7 Based on natural history data, 5- and 10-year survival rates for chordoma patients are 62 to 67% and 40 to 45%, respectively.5 However, for patients treated in modern case series with en-bloc resection and adjuvant radiotherapy, 5-year overall survival (OS) has been reported even higher for spinal chordomas.8–11 This chapter reviews the diagnosis and treatment of spinal chordoma, as well as the histological and genetic characteristics that facilitate diagnosis and are driving novel therapeutics. Current literature and classes of evidence supporting the use of en-bloc resection and adjuvant therapy are reviewed. Clinically, patients with chordoma most often present with pain. For patients with cervical spine chordoma, pain on neck flexion or rotation is most common. Myelopathy may be present if there is spinal cord compression. Thoracic and lumbar chordoma patients classically have local mechanical pain. Among all chordomas, sacral chordomas are the most common followed by lumbar chordomas. For patients with sacral chordoma, bowel or bladder dysfunction, saddle anesthesia, and foot drop or other gait abnormalities commonly occur, accompanied by local sacral pain. Neurologic compromise is less common for tumors in this region. Chordomas in the sacral spine grow slowly, gradually compressing the abdominal viscera, and patients may complain of chronic urinary retention, constipation, or pain that has progressively worsened over several months or years. For patients with large tumors, a mass may be palpable around the buttock. Further, sciatic type pain is not uncommon, radiating down the back of the leg to the bottom of the foot. In a middle-aged patient presenting with sacral pain and symptoms of cauda equina, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be performed to investigate the presence of a mass. On imaging, a chordoma may have a heterogeneously calcified appearance on plain radiographs. CT scans are more effective at capturing bony remodeling and destruction associated with chordoma growth, and evidence of widened foramina or thinning of cortical bone may be evident. Overall, MRI is the preferred imaging modality for exploring soft tissue extension associated with chordoma. Unlike other tumors of the spine, chordomas invade the disk spaces (Fig 8.1). On T1-weighted images, chordomas appear hypoto isointense to the vertebral bodies, and masses are likely to extend to adjacent levels and into the paraspinal musculature. Chordomas appear iso- to hyperintense to the bone on T2-weighted images (Fig. 8.1a) due to a high content of mucin or chondroid matrix, and these lesions may have moderate to robust contrast enhancement. Fat-suppressed MRI may be helpful to better delineate tumor margins (Fig. 8.1b). A 57-year-old man presented with a history of thoracic chordoma extending from the C7-T1 junction to the T3-4 disk space (Fig 8.1). He was initially informed that this was unresectable due to its location, and he was treated with traditional external beam radiation therapy and stereotactic radiosurgery; however, he continued to have progressive myelopathy. Fig 8.1a,b A heterogeneously hyperintense tumor was noted on T2-weighted (a) and fat-suppressed (b) imaging to extend from the C7-T1 junction to the T4 disk space with significant paraspinal extension. The lesion was proven to be a chordoma on biopsy. The patient was then offered staged surgery for en-bloc resection of the tumor. A posterior incision was made from C1 to T9 and subperiosteal dissection was completed from C2 to T8. Extensive dissection was made beneath the scapula bilaterally to visualize 7 cm from the midline. Cervical lateral mass screws were placed at C3-C6, with a rod inserted across the spinous process of C2 (Fig 8.2a). Thoracic pedicle screws were placed at T5-T8 and the ribs were dissected circumferentially and disarticulated at T2-T4 bilaterally. Care was taken to leave the tumor intact. Bilateral total laminectomy of C7-T4 was performed, as well as removal of the C7 lateral mass and the C7-T1 joint. The T1-T3 nerve roots were ligated and transected. Additional dissection of the esophagus and vessels was made and these structures were protected, and a Tomita saw was introduced at the T3-T4 disk space (Fig. 8.2a). Two contoured, tapered rods were placed bilaterally with connectors. Fig. 8.2a,b A computed tomography (CT) reconstruction of instrumentation following cervicothoracic chordoma resection. (a) Cervical lateral mass screws were placed at C3-C6, with a rod inserted across the spinous process of C2. Bilateral total laminectomies were performed at C7-T4. Thoracic pedicle screws were placed at T5-T8. A Tomita saw can be seen at the T3-T4 disk space. Two contoured, tapered rods were placed bilaterally with connectors. (b) Postoperative view of instrumentation with the cage visible anteriorly. The T3-T4 disk space was transected with the Tomita saw, and a C7-T1 discectomy facilitated en-bloc removal of the mass. A cage was packed with allograft bone from C7-T4. For the second stage of the procedure the following day, an anterior cervical incision was made and extended through the cervicothoracic junction. The C7-T1 disk space was exposed and the disk excised, disconnecting the cervical and thoracic spines. The patient was then placed in the left lateral decubitus position with his head in a Mayfield three-point fixator. The posterior midline incision was opened and the latissimus dorsi muscle and scapula were reflected to visualize the chest wall. Thoracic surgery assisted with the chest wall exposure, with a thoracotomy between the fourth and fifth ribs, to visualize the lung. The lung was retracted caudally and the parietal pleura was incised to access the wires of the Tomita saw. The T3-T4 disk space was then transected. The tumor was dissected from the surrounding structures without violating the tumor capsule, and the tumor was removed en bloc. Reconstruction with a titanium mesh cage packed with demineralized bone matrix from C7-T4 was performed (Fig. 8.2b). The posterior fusion was completed using decorticated laminar bone from T4-T8, and two chest tubes were placed. Plastic surgery assisted with the closure of the chest wall and musculature. The patient remained in intensive care for 4 days, and was discharged to inpatient rehabilitation 2 weeks after surgery. At 1 year after surgery, the patient had returned to full-time work. He had 5/5 strength in all extremities, with normal gait and fine motor skills in his hands. There was no evidence of residual tumor. He is alive 2½ years after surgery. Biopsy of the lesion should be conducted under CT guidance to avoid open biopsy and contamination of tumor margins. This consideration must be balanced with the pathologist’s need for tissue. At the time of biopsy, the skin incision should be carefully marked and excised en bloc in subsequent surgical procedures to prevent tumor seeding along the surgical tract. If a patient presents with a suspected chordoma, referral to a tertiary academic center is recommended for the biopsy to ensure the appropriate pathological diagnosis and treatment. Chordomas may present in a variety of histological subtypes, and due to the rarity of this lesion, pathologists may have trouble distinguishing chordoma from other tumor types. Conventional chordoma is characterized by cells with a lobulated architecture and abundant myxoid matrix. On histopathological examination, chordoma tissue is often arranged in a lobular arrangement known as physaliphorous with intracytoplasmic “bubbles.”1 Tumors are more aggressive if histological tumor necrosis or Ki-67–positive staining is found. Anaplastic features, including marked nuclear atypia or a sarcomatoid pattern and solid architecture, correlate with high proliferation, metastasis, and a poor prognosis. Tumors with increased amounts of chondroid matrix are known as chondroid chordoma. Cellular based lesions are atypical chordomas and those with high-grade spindle-cell differentiation are dedifferentiated chordoma, which is often highly aggressive and presents with increased risk of metastasis. With dedifferentiated chordoma, the lesion may transform to a high-grade lesion, typically fibrous histiocytoma, fibrosarcoma, or, less often, osteosarcoma or rhabdomyosarcoma. Outcome data for patients with dedifferentiated chordoma are limited to case reports and small cohort studies. A case study of four patients with dedifferentiated chordoma reported survival of 63 and 76 months for two patients following surgical resection, and two deaths at 7 and 9 months.12 The genetics of chordoma have been studied extensively in recent years. The transcription factor T (brachyury) is overexpressed in chordomas. In animal models, members of our group generated a novel chordoma cell line, JCH7, from a 61-year-old woman with sacral chordoma, and silenced the brachyury gene using shRNA (small or short hairpin RNA).13 This resulted in a 20 to 25% decrease in cell viability and cell size, as well as an arrest of cell growth and loss of the characteristic physaliferous cytoplasm. In a study using whole-exome and Sanger sequencing of brachyury in patients with chordomas and ancestry-matched controls, a common single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) was associated with chordoma risk.14 In a review of chordoma genetics and therapeutic targets, our group identified other chromosomal abnormalities, including deletions in 1p and 9p that are associated with uncontrolled cellular proliferation.15 These genes may serve as targets for novel therapies in the future. En-bloc resection refers to a surgical technique of removing a tumor in one piece without violating the tumor margins; however, it is the final margins reported by the pathologist that are of prognostic significance. The margins can be intralesional, marginal, or wide. Classically, a wide surgical margin involves en-bloc resection of the tumor without disruption of the tumor capsule and sacrifice of adjacent soft tissue. Although surrounding tissues may appear macroscopically uninvolved, locally invasive disease may be present at a cellular or microscopic level. Thus, wide margins provide the most thorough resection of the lesion. Other considerations, such as the proximity of the spinal cord and bowel, can limit the feasibility of wide marginal resection for spinal chordomas, unless functional impairment is accepted.16 Marginal resection involves the en-bloc removal of the tumor with dissection along the tumor capsule, which runs the risk of satellite tumor cells being left behind. In contrast, intralesional resection involves curettage and piecemeal resection of the tumor. Violation of the tumor capsule increases the risk of local tumor spillage and seeding along surgical margins, and almost always leaves residual tumor behind. En-bloc resection, with marginal or wide margins, unequivocally provides better long-term survival. The Spine Oncology Study Group (SOSG) issued a strong recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence and consensus expert opinion that en-bloc resection should be undertaken for surgical treatment of spinal chordoma.2 This was the result of a systematic review and ambispective multicenter cohort study by the SOSG.2 However, the language used in the chordoma literature is inconsistent. The terms gross total, radical, and en-bloc resection are often used interchangeably, with considerable variability based on the surgeon’s preferred terminology. In a literature review of peer-reviewed, PubMed-indexed, English-language articles from 1996 to 2011 with full text available, reporting data for en-bloc resection for chordoma, among studies with 94% or more patients undergoing en-bloc resection, the mean disease-free survival was 70 to 84.2 months (Table 8.1).

Chordoma

Introduction

Introduction

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Case Illustration

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

En-Bloc Resection

En-Bloc Resection

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree