Fig. 20.1

Patient selection criteria for Chopart’s amputation. (a) Gangrene encompassing the entirety of the forefoot may be considered for Chopart’s amputation depending on the viability of the proximal tissue. (b) Gangrene and large decubitus ulceration of the weight bearing surface of the heel make leg amputation a better choice as opposed to Chopart’s amputation

Staged Surgical Approach

Midfoot amputation secondary to acute infection is often performed in a staged manner. The first stage is an incision and drainage procedure or partial foot amputation which is left open for initial management of the infection. Care is taken to completely excise the ulceration while draining any abscess collection, as well as copious irrigation of the wound. A bone biopsy is procured if osteomyelitis is suspected. The second stage is typically performed 3–5 days later allowing the remaining tissues to demarcate and vascular intervention if needed. During the stage 2 operation, Chopart’s amputation is performed and closed as outlined below.

Traditional Chopart’s Amputation Technique

Dorsal and plantar flaps are created using a fishmouth-type incision with care to ensure tension-free coverage of the amputation stump. The goal of the incision is to preserve as much dorsal and plantar tissue as needed for closure after disarticulation through the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints. The medial and lateral apices are near midline just proximal to the level of disarticulation, with the plantar flap being slightly longer to avoid sutures on the weight bearing surface (Fig. 20.2). Incisions are made full thickness down to bone at a 90° angle to the skin surface preserving adequate flap thickness. No attempt is made to preserve the dorsal, plantar, medial, or lateral tendon structures unless planning to transfer the tibialis anterior tendon to the dorsal neck of the talus. Tendons are left in place within the flaps and allowed to scar down where they lay. Patients commonly maintain active dorsiflexion despite loss of insertion of all dorsiflexory tendons (Fig. 20.3). The dorsal flap is raised at the bone level in an effort to preserve a viable and vascularized flap. The Chopart’s joint is visualized, and sharp dissection is used to disarticulate at the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints (Figs. 20.4 and 20.5). Remodeling of the weight bearing surface of the anterior calcaneus helps to avoid prominent edges that may predispose to future skin breakdown (Fig. 20.6). Interrupted skin sutures are used to close the wound, and deep sutures are not needed or desired (Fig. 20.7). A no-touch suture technique is used to allow minimal handling of the dorsal and plantar flaps. Hash marks are helpful to preplan flap approximation with the expectation that slight puckering will occur due to the plantar flap being longer and broader than the dorsal flap.

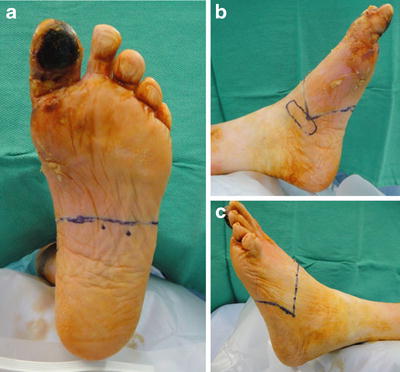

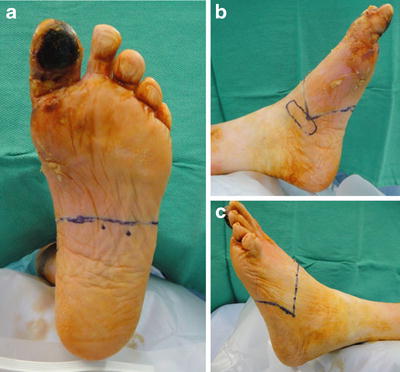

Fig. 20.2

Case 1: Traditional Chopart’s amputation technique with standard incision design. Chopart’s amputation incisions are drawn at the proximal demarcation of ischemic changes in the midfoot. (a) Note extensive gangrene on the plantar hallux with ischemic rubor extending along the medial forefoot despite recent vascular intervention. Localized digital gangrene would normally be treated with first ray amputation or perhaps TMA if not for vascular compromise in the plantar arch. (b, c)The medial and lateral incision apices are placed midline from dorsal to plantar, with an attempt to have matching dorsal and plantar flaps. The proximal extent of the medial and lateral apices is dictated by the anticipated level of bone resection but typically extend to the midtarsal joint. Note intact and viable tissue on the plantar weight bearing surface of the heel which makes this patient a candidate for Chopart’s amputation

Fig. 20.3

Active ankle dorsiflexion despite loss of the tibialis anterior tendon (TA) with Chopart’s amputation. Active dorsiflexion remains despite complete severing of the TA and extensor tendons with Chopart’s amputation. No attempt was made to transfer the TA yet active dorsiflexion is commonly seen which is thought to occur secondary to adhesion of the severed anterior tendons to surrounding soft tissues

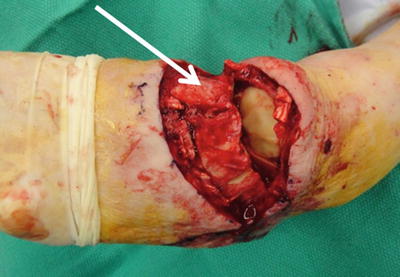

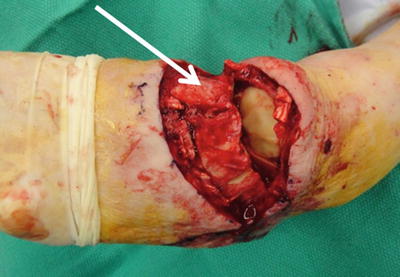

Fig. 20.4

Case 1: Full depth incision to preserve a viable dorsal flap. The dorsal flap was raised off the cuneiforms, cuboid and navicular to accomplish midtarsal joint disarticulation. Note how the exposed tarsal boness (arrow) are skeletonized after subperiosteal dissection in an effort to make the flap truly full thickness

Fig. 20.5

Case 1: Midtarsal joint disarticulation. The plantar flap was incised full depth directly to the tarsal bones. The plantar flap was much thicker than the dorsal flap and included muscle tissue as seen here. Note how the talus was stacked on top of the calcaneus which is the case for all but the most severely pronated foot types. This predisposes to excessive plantar lateral pressure beneath the anterior calcaneus which correlates with the most likely area of breakdown of the Chopart’s amputation stump. The cartilage may or may not be removed prior to closure depending on surgeon’s preference although we typically leave the cartilage intact

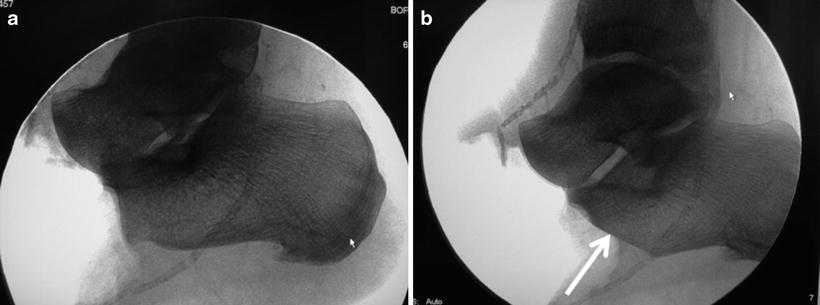

Fig. 20.6

Case 1: Remodeling of the anterior calcaneal weight bearing surface. (a) Intraoperative image demonstrated a natural plantar prominence of the anterior calcaneus after removal of the cuboid. The talus bears minimal weight with Chopart’s amputation and anterior calcaneal remodeling is helpful to avoid lateral tissue breakdown. The surgeon should assume that the foot will function with maximum plantarflexion of the talus within the ankle joint mortise, and complete loss of calcaneal inclination despite any attempt at tendon balancing. (b) The anterior aspect of the calcaneus was remodeled to create a natural plantar rocker bottom contour (arrow). The resected portion of the anterior calcaneus was procured for clean margin biopsy

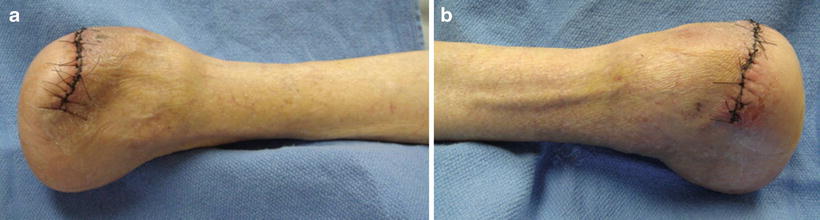

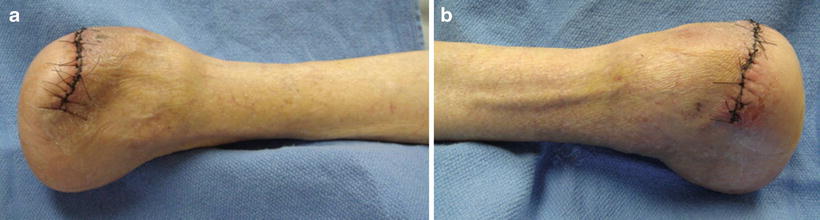

Fig. 20.7

Case 1: Chopart’s amputation stump at 2 weeks postoperative. Prompt healing was achieved due to the appropriately selected level of amputation based on local vascularity and tissue quality. The traditional dorsal and plantar flap technique preserved the weight bearing pad of the heel. The short nature of the Chopart’s amputation stump allowed bipedal weight bearing for transfer and limited walking with a prosthetic but greatly compromised foot function

Modified Chopart’s Amputation Technique (Naviculocuneiform Disarticulation)

Our preferred “Chopart’s” amputation technique involves preservation of the navicular provided that the soft tissue flaps can provide adequate coverage of the longer stump. This naviculocuneiform level of amputation is a unique approach that has advantages from a biomechanical standpoint. The traditional Chopart’s level of amputation results in complete loss of calcaneal inclination angle, maximum plantarflexion of the talus within the ankle joint mortise, and overload of the lateral column. The head of the talus bears minimal to no weight, and tendon balancing does not actually balance these deformities. Preserving the navicular allows weight transfer through the medial column by extending the reach of the talar head in an attempt to provide improved balance of the amputation stump due to equal length of bone anterior and posterior to the ankle joint. This approach also preserves the insertion of the posterior tibial tendon which could be released if there is concern for inversion deformity. The cartilage on the exposed navicular is left undisturbed although some dorsal remodeling may be necessary to round off the dorsal edge. Figure 20.8 discusses the intended functional benefit of preserving the navicular.

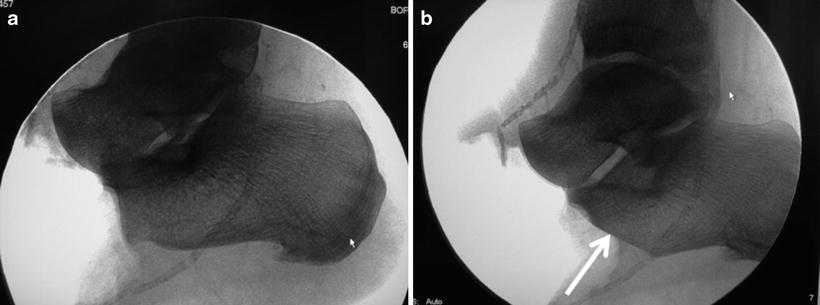

Fig. 20.8

Postoperative radiographs demonstrating traditional and modified Chopart’s amputation levels of bone resection. (a) The head of the talus does not bear weight after Chopart’s amputation, unless the arch was severely pronated prior to surgery. (b) Preservation of the navicular creates a rocker bottom forefoot with the intent to decrease lateral stress beneath the anterior calcaneus where tissue breakdown is common following this procedure. Note that the plantar aspect of the distal calcaneus has been remodeled to minimize pressure in this region. Navicular preservation also achieves a fairly similar foot length both in front of and behind the talar dome. This assists with balance of the amputation stump through the ankle and minimizes the expected plantarflexion of the talus which is demonstrated on this weight bearing X-ray

Angiosome-Based Plantar Flap Options

Significant compromise of the plantar soft tissue may suggest that BKA is the better level of amputation, especially when the plantar heel soft tissue is compromised from neuropathic ulceration, gangrene, or decubitus ulceration. Angiosome-based plantar flaps are available which take advantage of direct inflow from the medial or lateral plantar arteries as described in Chap. 19 [12]. Case 2 (Figs. 20.9, 20.10, 20.11, 20.12, 20.13, 20.14, and 20.15) demonstrates our preferred approach to lateral column midfoot ulceration complicated by osteomyelitis of the cuboid which involved a medial plantar artery angiosome (MPAA) rotational flap. The lateral plantar artery angiosome (LPAA) flap allows coverage of wound defects in the medial arch. Combined MPAA and LPAA flaps create a V to T planton flap which are used for central wound defects associated with plantar space infections as shown in Case 3 (Figs. 20.16, 20.17, 20.18, 20.19, and 20.20).