Cervical Laminoplasty

Nikhil A. Thakur

John G. Heller

The concept of laminoplasty was introduced in 1972 by Oyama and Hattori. Their “expansive Z-laminoplasty” was developed to address the unsatisfactory outcomes of patients undergoing laminectomy for myelopathy due to multilevel cervical spondylosis. Hirabayashi then introduced the “open-door” laminoplasty technique in 1977, followed by the Kurokawa double-hinge, or “French door” technique in 1980. Subsequently described techniques for laminoplasty are modifications of these two principal concepts, with variations seen in how the laminoplasty is held open as well as the exposures used. More recently, efforts continue to refine the criteria for selecting the levels to be decompressed, appropriate sagittal configurations, and postoperative rehabilitation methods.

INDICATIONS

Laminoplasty rapidly gained popularity in Japan in the treatment of cervical myelopathy due to ossified posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) and multilevel cervical spondylosis. That these innovations might originate in Japan stands to reason, given the high rates of OPLL and congenital cervical stenosis in that population.

Today, indications for laminoplasty have expanded to some degree. Arguably, it remains the method of choice for treating cervical myelopathy due to OPLL and multilevel spondylosis involving three or more motion segments (Fig. 9-1). Other indications include spinal cord decompression to salvage a failed anterior cervical decompression and fusion (ACDF) procedure, recurrent myelopathy due to adjacent segment disease after ACDF, and as a primary treatment of myelopathy in hosts at increased risk for nonunions (i.e., smokers and patients with metabolic bone disease). Laminoplasty is particularly well indicated in patients with developmentally narrow spinal canals (midbody anterior posterior [AP] diameter less than 12 mm), since spinal canal expansion directly treats the underlying primary pathology. This use should be particularly appealing, as 50% of patients undergoing ACDF for cervical spondylotic myelopathy have relative (less than 13 mm) or absolute (less than 10 mm) developmental spinal canal stenosis.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Laminoplasty is relatively contraindicated in the following situations: (a) epidural fibrosis (i.e., following infection, previous posterior spinal surgery), (b) large “hill-shaped” lesions of OPLL (8) that occupy more than 50% to 60% of the AP canal diameter, (c) axial neck pain as the patient’s primary clinical complaint, and (d) fixed kyphosis greater than either 5 degrees or 13 degrees, depending on certain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) characteristics. Additional potential reasons to select an alternative procedure include morbid obesity and diabetes mellitus, which can result in a two- to eightfold increase in surgical site infections, particularly with a posterior cervical approach, let alone the technical challenges related to positioning these patients on the operating table and surgical exposure.

With regard to the overall alignment of the cervical spine, lordotic or straight spines have been reported to have statistically significantly higher functional recovery outcomes than kyphotic or sigmoid-shaped curves after laminoplasty (26). Suda et al. (26) recommended patients whose cervical spines range from lordotic to 13 degrees or less of kyphosis as ideal candidates for

laminoplasty if there is no cord signal change on the T2-weighted MRI. If there is cord signal hyperintensity on the T2-weighted MRI, then the upper limit of acceptable preoperative kyphosis is 5 degrees or less. Note that the presence of a lordotic alignment is not a prerequisite for performing a laminoplasty. This myth is born of misinterpretation of the literature, which seems to have taken on a life of its own as it is repeated in text after text without an objective review of the original studies.

laminoplasty if there is no cord signal change on the T2-weighted MRI. If there is cord signal hyperintensity on the T2-weighted MRI, then the upper limit of acceptable preoperative kyphosis is 5 degrees or less. Note that the presence of a lordotic alignment is not a prerequisite for performing a laminoplasty. This myth is born of misinterpretation of the literature, which seems to have taken on a life of its own as it is repeated in text after text without an objective review of the original studies.

TYPES OF LAMINOPLASTY

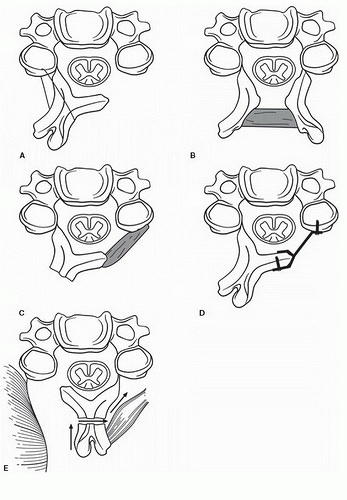

The two major schools of laminoplasty derive from the Hirabayashi “open-door” procedure and Kurokawa’s “French door” laminoplasty technique. Other subsequently described techniques are variations on these themes. These techniques are illustrated in Figure 9-2. Most differ either in how the surgeon secures the laminae in their new position or in how the exposure is made (Fig. 9-2E). Initially, hinges were either tethered open with suture or wire or propped open with bone grafts or other spacers, such as ceramic or polyethylene blocks. Use of laminoplasty plates has become more frequent, particularly in the United States, and is often the mainstay at many centers. These are used either in isolation or in conjunction with bone grafts. The latter are not necessary for success since permanently maintaining the “open” position rests on healing of the hinge.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

Preoperative Workup

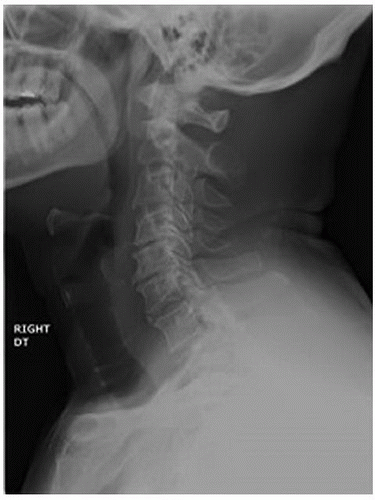

The preoperative diagnostic imaging workup should consist of plain radiographs of the cervical spine, including AP and neutral lateral radiographs (Fig. 9-3). Flexion-extension films have been shown in some studies to be useful in determining presence of segmental instability. Sakai et al. (23) showed that presence of a retrolisthesis resulted in significantly lower Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) recovery rates as compared to anterior spondylolisthesis or no spondylolisthesis (which had equivalent outcomes). Masaki et al. (16) further observed that hypermobility at the point of maximum spinal cord compression could further compromise neurologic recovery rates, which suggested that another surgical strategy might be wise, such as adding a fusion.

FIGURE 9-2 Various methods to perform a laminoplasty. (Reprinted from Rao RD, Gourab K, David KS. Operative treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88(7): 1619-1640, 2006, with permission.) |

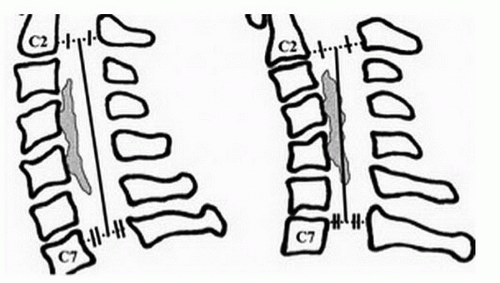

The “K-line” or “kyphosis line” concept was introduced by Fujiyoshi et al. (3) as a tool to determine if laminoplasty could be used successfully in patients with OPLL. This tool can also be extended to address large ventral lesions or fixed kyphoses, which are often contraindications to laminoplasty. On a lateral cervical radiograph, the K-line was defined (3) as the line connecting the midpoints of the spinal canal at C2 and C7 (Fig. 9-4). A (+) K-line did not have an OPLL lesion crossing it, whereas a (-) K-line was present when the pathology extended dorsally beyond the line (Fig. 9-4). In K-line positive group, the average neurologic recovery rate following laminoplasty was 66% compared to 19% in the K-line negative group.

An MRI study is useful in preoperative planning to determine which levels need to be included in the laminoplasty. Moreover, an MRI allows the surgeon to determine if a C2 dome laminectomy

should be included with the laminoplasty technique. Hypertrophied flavum, congenital stenosis, cervical spine lateral architecture, etc. can result in impingement of the cord at the C2 level after laminoplasty due to cord drift back and cause postoperative myelopathy.

should be included with the laminoplasty technique. Hypertrophied flavum, congenital stenosis, cervical spine lateral architecture, etc. can result in impingement of the cord at the C2 level after laminoplasty due to cord drift back and cause postoperative myelopathy.

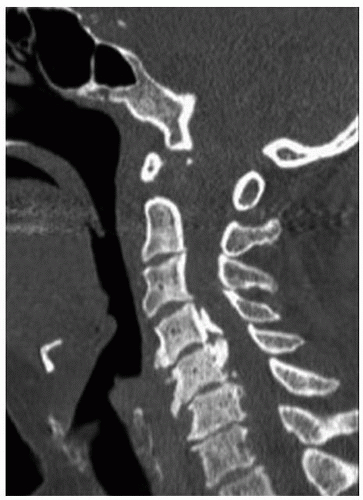

The use of a computed tomography (CT) study or a CT/myelogram study is surgeon and patient specific. A CT scan gives the surgeon a more precise appreciation of the bone anatomy including presence of OPLL (Fig. 9-5), ossified ligamentum flavum, and foraminal stenosis due to osteophyte formation. Foraminal stenosis detected on CT and correlated with physical examination can be addressed during the surgical procedure with a foraminotomy on the affected side. The use of myelography enhances structural detail including details of patterns of compression and thickness and shape of lamina. At times, it is indicated when the patient’s MRI leaves some doubt about the nature and extent of the pathology. A CT scan also helps determine the “occupation ratio” for a large ventral lesion (AP diameter of the lesion/AP diameter of the canal × 100). An occupation ratio of greater than or equal to 50% to 60% should temper any expectations about postoperative neurologic improvement. All of these additional anatomical details can be important tactical information to be used intraoperatively.

Room Setup/Patient Positioning

Laminoplasty is performed in the prone position. The authors recommend that the patient’s comfortable range of motion be assessed preoperatively, so that they can be positioned in some flexion (flexed-chin-tucked position) during surgery. The advantages to this include the following: (a) cervical extension may result in worsening of canal stenosis and cord compression, and (b) the procedure is technically easier as the overlap or “shingling” of the laminae is reduced (Fig. 9-6). This also helps with excessive skin folds in some patients.

A Mayfield three-pin head holder is used to immobilize the cervical spine, as well as to protect the face and eyes. Longitudinal bolsters are placed on the lateral border of the chest to take pressure off the central chest and abdomen. Knees and ankles are flexed to reduce lower extremity neural tension. Taping of the shoulders is not necessary. Tape may be used to shift the redundant soft tissues when needed in obese patients. A reverse Trendelenburg position is used to decrease venous pressure, thereby decreasing intraoperative blood loss.

Special Instruments/Equipment/Implants

Somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs) are generally recommended during laminoplasty procedures for myelopathy. In the authors’ opinion, the routine use of motor evoked potentials (MEPs) is open to discussion. Monitoring EMGs is an option when foraminotomies are added to the operative plan. Neuromonitoring may also serve to identify potentially significant episodes of hypotension or decreases in spinal cord perfusion. In both of these circumstances, early detection of a potential problem allows for rapid intervention and neurologic protection. More importantly, we prefer to use an arterial catheter for continuous monitoring of the mean arterial pressure, which is kept at a suitable level by whatever means necessary.

Roh et al. (22) reported the largest series of patients undergoing cervical spine procedures with SSEP monitoring. The authors found that degradation of SSEPs from baseline was seen in 17 of 809 (2.1%) patients, which prompted intervention and may well have prevented neurologic sequelae in 15 of these 17 patients (88%). The authors noted that monitoring may also help identify brachial plexopathies associated with positioning (e.g., taping down the shoulders), particularly in obese individuals (22). The use of MEPs has been shown to be beneficial in cervical spine surgery as an adjunct to SSEP. A recent article demonstrated that MEPs were more sensitive to changes associated with cervical myelopathy than SSEPs during intraoperative monitoring (4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree