Fig. 17.1

Lesser metatarsal transfer lesions are common following partial ray resection or metatarsal head resection. Biomechanically, the metatarsal parabola is disrupted, leading to excessive peak plantar pressure below the adjacent metatarsal heads, leading to soft tissue breakdown, poor healing potential, and high likelihood of eventual infection. This is illustrated with a case exhibiting a (a) pre-ulcerative tranfer lesion and (b) a patient with full-thickness ulceration of the second ray following prior first ray amputation

Prevention of Central Metatarsal Osteomyelitis in Patients with Neuropathic Ulceration

When assessing the patient with a neuropathic ulceration below a central metatarsal head, recognizing the structural etiology is of the utmost importance so that any biomechanical abnormalities can be appropriately addressed. In patients with pre-ulcerative hyperkeratotic lesions or uncomplicated superficial ulceration, conservative offloading measures can be employed. Such strategies for offloading the middle column include accommodative orthoses, shoe modifications, total contact casting, traditional casting, various ankle-foot orthoses, Charcot restraint orthotic walkers (CROW), integrated prosthetic and orthotic system (IPOS) shoes, and surgical offloading measures. The total contact cast has traditionally been described as the gold standard for offloading low- to mid-grade forefoot and midfoot diabetic neuropathic ulcerations, as a 75–84 % reduction in peak plantar pressures during weight bearing has been demonstrated [1]. Oftentimes, temporary offloading strategies are beneficial in allowing an uncomplicated open wound to heal prior to undergoing preemptive surgical correction of the causative deformity in the patient without surgical contraindications. If the etiology of the ulcer is not effectively addressed with either permanent conservative or surgical methods, recurrence or persistence of the ulcer is probable. Many nonhealing neuropathic ulcers eventually become complicated, developing deep infection with abscess and osteomyelitis. Consideration should be given to pursuing early surgical intervention in an attempt to alter the course of a perpetual wound and avoid limb loss.

Surgical Modalities for Prophylactic Correction of Structural Deformity

Central metatarsal neuropathic ulcers can be treated surgically either in a prophylactic manner prior to the development of an acute infection or in an urgent manner once infection necessitates intervention. If a contributing structural deformity is identified and relative contraindications to surgery are low, there is often value in correcting this deformity prior to the development of worsening ulcer condition and infection. For instance, ankle equinus is a common cause of plantar metatarsal head ulceration, making tendo-Achilles lengthening (TAL) or gastrocnemius recession an effective adjunct to local wound management. It is important to identify whether the gastrocnemius or gastrosoleal complex is contributory to the equinus. We tend to perform TAL for the diabetic with low activity level but profound contracture or those with recurrent sores despite prior forefoot amputation. Gastrocnemius recession is often reserved for the more active diabetic with less profound deformity to minimize the potential for developing a calcaneus gait. TAL or gastrocnemius recession can be performed in an open manner in an attempt to better control the amount of lengthening achieved provided soft tissues are amenable. Case 1 demonstrates open equinus correction to trent forefoot ulceration (Figs. 17.2, 17.3, and 17.4). The patient with profound lower extremity edema or poor skin quality with concerns for healing may be a better candidate for percutaneous lengthening. While not an absolute contraindication, the surgeon should take precautions to isolate the clean procedure site from any contaminated areas when performing tendon surgery concomitantly with open wounds or wound surgery. Staged surgery in acute infection cases is an effective means to achieve this separation. Mueller demonstrated the effectiveness of TAL on healing plantar forefoot wounds with a randomized clinical trial of patients treated with either total contact cast alone or with TAL. Two-year follow-up revealed an 81 % ulcer recurrence rate in the total contact cast cohort but a 38 % recurrence in the cast and TAL group [2].

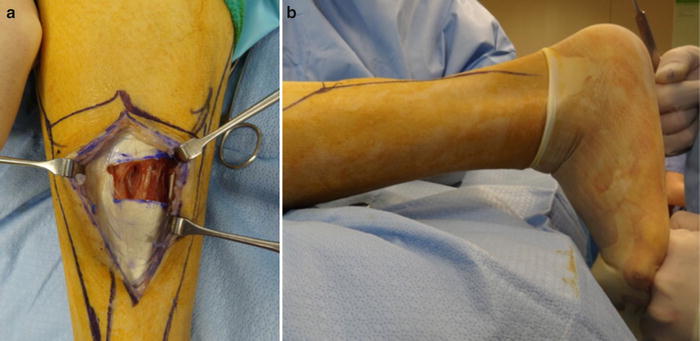

Fig. 17.2

Case 1: Nonhealing forefoot ulcers associated with ankle equinus. Limited ankle dorsiflexion is shown here with the knee in the extended position. Flexing the knee significantly improved ankle joint dorsiflexion indicating isolated gastrocnemius equinus. Ankle equinus increases peak plantar pressure to the forefoot contributing to recalcitrant neuropathic forefoot ulcers. Equinus deformity is difficult to manage conservatively and posterior lengthening is warranted

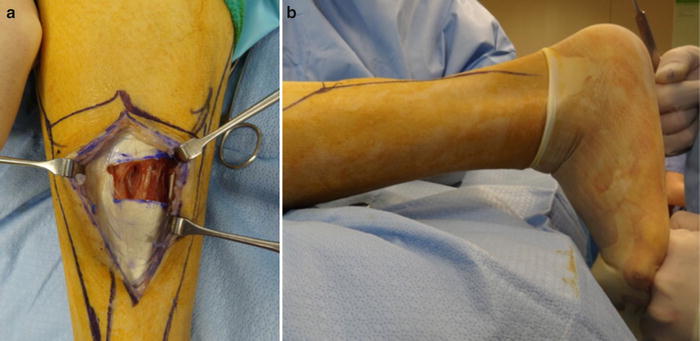

Fig. 17.3

Case 1 with open gastrocnemius recession. (a) We prefer gastrocnemius recession for the relatively more active diabetic patient with forefoot ulceration associated with less profound equinus deformity in an effort to minimize loss of strength and potential for development of calcaneus gait. We reserve Achilles tendon lengthening (TAL) for midfoot ulceration associated with prior midfoot amputation or Charcot arthropathy. Open gastrocnemius lengthening requires healthy soft tissues in the calf region, and uncontrolled edema is a relative contraindication since incision healing may be compromised. TAL can be performed percutaneously under these conditions. (b) Note that a sterile glove is placed over the prepped foot ulceration. Post lengthening ankle joint dorsiflexion is shown here with the knee extended and the foot dorsiflexed beyond 90° confirming successful release of equinus

Fig. 17.4

Preop and 2-week post-op clinical appearance in casel. Once the contributory equinus deforming force is corrected, external pressure on the ulceration site is decreased. The clinical appearance preoperatively (left) reveals a full-thickness ulceration that is nearly fully epithelialized by 2 weeks postoperatively (right)

There are many other structural deformities that may need to be addressed in a preventative manner. An elongated or plantarflexed metatarsal predisposing to plantar metatarsal head ulceration can be addressed with a metatarsal shortening osteotomy or dorsiflexory wedge osteotomy. Medial column insufficiency associated with hallux valgus deformity leading to lesser metatarsal head overloading is another common etiology. Correction of the medial column insufficiency with midfoot fusion may be necessary. Similarly, digital contracture can play a role in metatarsal head prominence, with retrograde forces from the digit causing plantar flexion of the metatarsal, which may necessitate repair of the digital deformity. The aforementioned reconstructive procedures intended for wound prophylaxis should be used with discretion as this patient population is at high risk for additional complications. Fleischli illustrated this with a reported 32 % incidence of acute Charcot neuroarthropathy following dorsiflexion metatarsal osteotomy [3]. Furthermore, elective reconstructive procedures are not typically employed if there is suspicion for infection. The wound would ideally be fully healed prior to reconstructive bone procedures requiring internal fixation, although this is not always feasible. The surgeon should use discretion when considering placing internal fixation in an area with previous ulceration and potential for subclinical osteomyelitis. Complete clinical, radiographic, and laboratory assessment to rule out low-grade infection is prudent in this situation. If concern persists in regard to performing reconstructive procedures requiring internal fixation, localized procedures such as metatarsal head resection are oftentimes effective at addressing the underlying biomechanical deformity. However, such endeavors should only be attempted when necessary as potential for transfer lesions or complicating heterotopic ossification (HO) can negatively affect the anticipated outcome.

Surgical Management of Central Metatarsal Infection

Surgical intervention for central metatarsal infection is common in the setting of infection spreading proximally from a digital wound or an infected neuropathic ulcer below the metatarsal head. Infection in these settings can manifest as acute soft tissue abscess, gas gangrene, acute or chronic osteomyelitis, unrelenting cellulitis with associated ulceration, or nonviable wet gangrene. Lack of viable soft tissue for primary closure of a lesser digital wound associated with proximal ulceration, necrosis, gangrene, or vascular insufficiency may necessitate surgical intervention at the metatarsal level as well. Central ray procedure options generally consist of single or multiple metatarsal head resection, partial or complete ray resection, or transmetatarsal amputation (TMA). Careful evaluation of the underlying pathomechanics, viability of surrounding soft tissues, size of the local wound defect, and extent of osteomyelitis is critical in selecting the optimal procedure.

Isolated Central Metatarsal Head Resection

Central metatarsal head resection can be an effective procedure in the setting of an isolated plantar metatarsal head ulceration. Full-thickness plantar metatarsal head ulcers with exposed bone most likely involve osteomyelitis with concomitant sepsis of the MTP joint. In the patient with a wound probing to bone and exhibiting underlying structural deformity but no acute soft tissue cellulitis or abscess, the surgeon may consider performing isolated metatarsal head resection in order to remove the infected bone and obtain bone biopsy while concomitantly addressing the underlying structural deformity. Early surgical intervention once the bone becomes exposed can limit the amount of resection required, as morbidity increases if the local soft tissues become acutely infected, raising the risk for systemic sepsis and more proximal foot amputation or limb loss.

When considering isolated metatarsal head resection, appropriate imaging modalities such as MRI are useful to evaluate for involvement of the adjacent proximal phalanx, determine the extent of proximal osteomyelitis extension in the metatarsal, and assess for associated deep abscess. Indications for isolated metatarsal head resection include osteomyelitis that appears to be contained to the metatarsal head with minimal adjacent soft tissue involvement. Metatarsal head resection can be performed under monitored anesthesia care with a local anesthetic block. If the plantar metatarsal head ulceration is full-thickness in nature, it is typically excised in full-thickness fashion and closed primarily (Fig. 17.5). Partial thickness ulcerations may be superficially debrided and allowed to heal secondarily. The metatarsal head can be accessed via a dorsal incision directly over the distal metatarsal as demonstrated in case 2 (Fig. 17.6 and 17.7). Alternately, if proximal extension of a plantar incision is necessary for debridement purposes, the metatarsal head could be resected through a single plantar incision. A saw is introduced into the dorsal incision and used to resect the metatarsal head immediately proximal to the metaphyseal flare. Care is taken to bevel the cut in a slightly dorsal-distal to plantar-proximal manner to avoid subsequent prominences on the weight bearing surface (Fig. 17.7). A grasping device is then used to remove the metatarsal head via a rolling motion, where the head is purchased on the medial and lateral aspects and twisted away from its periosteal attachments. The bone is inspected for clinical signs of osteomyelitis, including intraosseous purulence, medullary bone compromise, and cortical erosion. The specimen is sectioned into two pieces for microbiologic and pathologic analysis. The environment should be inspected for proximal tracking of soft tissue infection, particularly in the flexor and extensor tendon sheaths. The base of the proximal phalanx is also evaluated to assess for signs of infection and may require associated digital amputation if phalangeal involvement appears likely. If no purulence or cellulitis is present, primary closure is performed at the time of bone resection. When feasible, primary closure is desirable in order to promote prompt healing of the soft tissue often while the patient remains on antibiotic therapy. Continued bone exposure while attempting to heal the area by secondary intention is less desirable, particularly when the wound persists beyond the duration of antibiotic therapy.