Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate differences in total center of pressure (TCOP) paths during a Sit-to-Walk task in young and elderly subjects.

Method

Nine young and 19 elderly subjects were asked to repeat five Sit-to-Walk tasks. The COP paths were computed during the rising from vertical forces.

Results

For 4 young and 17 elderly subjects, the TCOP moved on the anterior-posterior axis during the 1st period (from the beginning of the rising to maximal force under the swing leg) and then joined the stance foot during the 2nd period (from maximal force to the toe off). For the two other paths observed in young subjects, the duration of the 2nd period was increased (33% of total duration vs. 18%, P = 0.02) or the area of TCOP displacement during the 1st period was decreased.

Conclusion

During the Sit-to-Walk task, different TCOP paths can be described in relation to age. These profiles are influenced by the level of postural stability required before initiating the first step. After further validation, the analysis of TCOP paths could be used to estimate the level of postural ability, especially in the elderly.

Résumé

Objectif

Examiner les différences des déplacements du centre de pression global (CdPG) pendant une tâche de transfert assis-marche chez des sujets jeunes et âgés.

Méthodes

Neuf sujets jeunes et 19 sujets âgés ont effectué cinq transferts assis-marche. Les déplacements du CdPG étaient calculés à partir des forces verticales.

Résultats

Chez 4 sujets jeunes et 17 sujets âgés, le déplacement du CdPG au cours de la 1 re période (du début du lever au pic de force verticale sous le pied oscillant [PV]) suivait l’axe antéropostérieur avant de rejoindre le pied d’appui au cours de la 2 e période (du PV au décollement du pied oscillant). Deux autres profils, observés chez les sujets jeunes, se distinguaient soit par une augmentation de la durée de la 2 e période (33 % de la durée totale vs 18 % ; p = 0,002) soit par une réduction de la surface de déplacement du CdPG au cours de la 1 re période.

Conclusion

Au cours du transfert assis-marche, plusieurs profils de déplacement du CdPG peuvent être décrits en fonction de l’âge. Ces profils sont influencés par le niveau de stabilité posturale requis avant la réalisation du premier pas. Après validation complémentaire, l’analyse de ces profils pourrait être utilisée pour estimer le niveau de compétence posturale, en particulier chez le sujet âgé.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Rising from a chair is an important task of daily life. With aging, the ability to stand up safely tends to decrease and the sit-to-stand is an essential part of the tests assessing balance in elderly . Numerous studies that focus on the Sit-to-Stand task (STS) examined biomechanical and neurophysiological parameters both in young and in elderly subjects . Because rising from a chair is commonly followed by a movement , Sit-to-Walk task (STW) which appeared to be a more functional task, was studied in young subjects , elderly subjects , stroke patients and patients with Parkinson’s disease . All authors agree that this task requires a more demanding control of balance than the STS task.

In healthy subjects, two strategies were identified for the STW task respectively related to postural stability and gait initiation . The total center of pressure (TCOP) initially located between the two feet reached the support foot laterally for the first strategy and obliquely towards the anterior part of the support foot for the second strategy . The authors concluded that the step could be initiated sooner in the second strategy .

People with Parkinson’s disease or elderly people with fear of falling may have difficulties in the STW dividing the task first by sit-to-stand then stand-to-walk . This strategy may be used to favor stability before gait initiation and therefore decrease the risk of fall during the task. In agreement, elderly seem to initiate gait later than young people to assure stability during STW and avoid falls .

TCOP displacement seems to be a good tool to identify some strategies during the STW but to date only one study describes TCOP displacement during STW in young healthy people . The aim of this study was to investigate TCOP displacement during STW in young and elderly subjects. Since elderly seem to initiate gait later than young people , we hypothesized that the difference should be visible on TCOP paths.

1.2

Methods

1.2.1

Subjects

Nine young healthy adults (5 males and 4 females, mean age: 24 years ± 3.4) and 19 healthy elders (6 males and 13 females, mean age: 74.2 years ± 5.9) participated to the experiment. In the elder group, the subjects presented no neurological or muscular disorders and no gait or balance trouble, lived at home and were independent in their daily life activities. None had any chronic deficiencies associated with a neurological, rheumatologic or orthopedic affection and none had any chronic or acute illness leading to an inflammatory syndrome. Finally, none of them had psychiatric disorders or dementia. All could stand up and walk unaided.

In the young group, all were devoid of any muscular, neurological or orthopedic pathology. None of the young subjects was sedentary and all practiced regular physical activity but not at a high level and not in competition.

All subjects gave their written informed consent and the procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards in the Declaration of Helsinki. Our local ethic committee specifically approved experiments performed in this study.

1.2.2

Instrumentation

For the young group, two force platforms on the floor (AMTI, Advanced Mechanical Technology, Inc., Watertown, USA) were used to record and digitize (1 KHz) the three components of the ground reaction forces (GRF). For the elder group, F-Scan soles (Tekscan, Inc., South Boston, USA) were used to acquire bipedal plantar pressure and vertical GRF. We followed the calibration procedures of the two systems used. As described in the litterature , the correlation between parameters recorded by both systems seems to be satisfactory and with a strict respect of use procedures, comparison of measurements is possible.

1.2.3

Test procedures

All subjects sited on an armless backless chair with their arms on the chest and each foot on a force plate. In order to minimize the influence of subjects’ height, we measured the shank height from the lateral condyle of femur to the floor and we adjusted the seat at 100% of shank height. The instruction was “after the « GO » signal, you will walk at a comfortable speed up to the marker 5 meters ahead”. In order to keep the nature of STW, the experimenters did not mention the need to stand up before walking. Each subject performed 5 trials.

1.2.4

Data analysis

For each foot, the center of pressure (COP) is the application point of the GRF. Both force platforms and pressure soles provided the coordinates of the COP. Using the position of the COP under each foot and the vertical component of the GRFs, we computed the total COP (TCOP), i.e. the barycenter of both COPs. TCOP paths in the horizontal plane (antero-posterior axis [AP] and medio-lateral axis [ML]) were analysed from the beginning of the rising to the toe-off of the swing leg. The beginning of the rising was the time when the vertical force exceeded the mean vertical force calculated during the first 200 ms of the recording + 2 standard deviations. The end of the rising was the time of the toe-off of the swing leg, when the force under swing foot was zero.

Averaged signals (force and paths) were calculated using the five trials.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 19 (IBM Corporation, USA). After verifying the normality of the distribution of the variables, a one-way Anova analysis with post-hoc Scheffe test was used to compare means. Results were considered statistically significant for P < 0.05.

1.3

Results

1.3.1

COP path of young subjects

At the beginning of the rising, the TCOP was most of the time located near the ankle line at mid-distance between the feet. A first period was defined between the beginning of the rising and the time when the vertical force under the swing foot reached its maximal value. Then, we observed a second period ended at the end of the rising. During this second period, TCOP moved towards the swing foot.

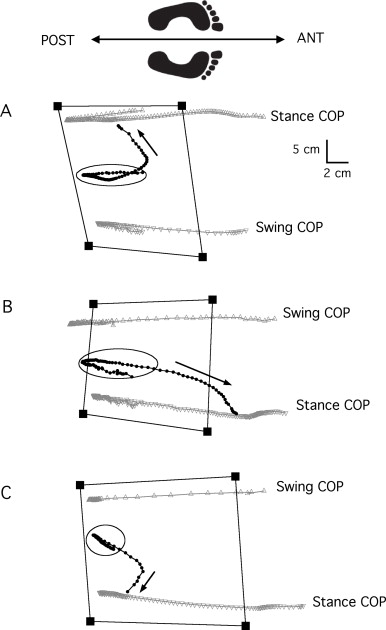

Different COP displacements were observed ( Fig. 1 ).

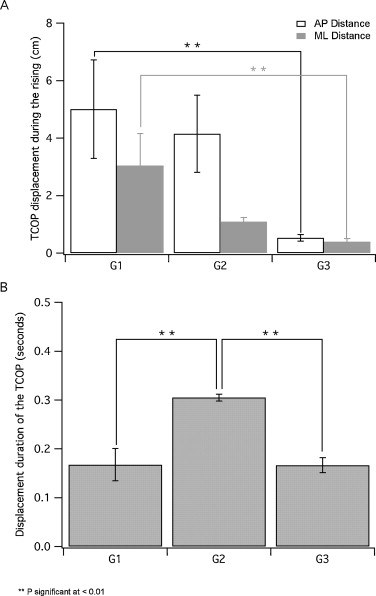

For the first group, (4 subjects, Fig. 1 A), during the rising, the TCOP stayed in an area (mean AP 5 ± 1.7 cm long, mean ML 3 ± 1.1 cm wide) centered at mid-distance between the feet and at the level of half feet. Then, it moved in parallel to the ML axis toward the mid part of the stance foot where it merged with the COP of the stance foot. The mean time of this second period was 0.17± 0.03 seconds (18% of total duration of the rising).

Two subjects ( Fig. 1 B) differed from the first group. At the beginning of the rising, the TCOP stayed in an area similar to the first group (mean AP 4.1 ± 1.3 cm long, mean ML 1.1 ± 0.1 cm wide). The TCOP moved forwards reaching the anterior part of the stance foot ahead of the metatarsial line. This second period lasted 0.3 ± 0.007 seconds (33% of total duration of the rising) and was longer than for the first group ( P = 0.002) ( Fig. 2 B ).

Finally, for three subjects ( Fig. 1 C), the TCOP stayed at mid-distance of the two feet, in an area smaller than that of the first group (mean AP 0.5 ± 0.1 cm long, P = 0.01; mean ML 0.4 ± 0.1 cm wide, P = 0.01; Fig. 2 A) and then moved obliquely and rapidly toward the mid-part of the stance foot where it merged with the COP of the stance foot. This second phase lasted 0.16 ± 0.01 seconds (22% of total duration of the rising). This duration was similar to that of the first group and shorter than for the second group ( P = 0.9 and P = 0.003 respectively) ( Fig. 2 B).

1.3.2

COP path of elderly subjects

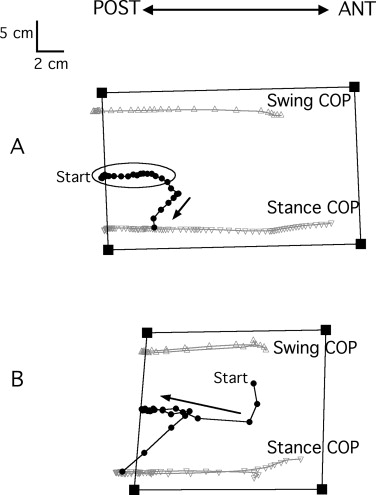

For 17 subjects TCOP paths were similar ( Fig. 3 A ). At the beginning of the rising, the TCOP was located back to the ankles line and close to the mid-distance between both feet. During the rising, it stayed in an area (AP length 3–7 cm, ML width 5 cm) lying at mid-distance between the two feet and ahead of the ankles line. At the end of the rising, it moved laterally and slightly backwards to reach the stance foot almost in front of the ankle where it merged with the COP of that foot.

Two subjects had a different path ( Fig. 3 B). At the start of rising, their TCOP was located almost at mid-distance of the ankles. During the rising, it moved backwards obliquely and reached the stance foot at the level of the ankle where it merged with the COP of that foot.

1.4

Discussion

The objective of this study was to describe and compare COP displacements between young people and elderly during a functional task of rising from a chair, the sit-to-walk.

The first paths described for the elderly and youth seem to be similar ( Figs. 1A and 3A ). Because the TCOP stayed in an area at mid-distance between each foot, it can be concluded that those subjects rose keeping an almost vertical postural orientation and that walking was initiated at the end of the rising. This behavior was identified as a strategy that favors a postural stability and it seems to be preferred by the elderly. Elderly with fear of falling divide the STW task into two phases indicating the need to stabilize before starting to walk: the sit-to-stand and the stand-to-walk . This division of the task could be observed on the TCOP path, when TCOP stays in a small area at mid-distance between each foot as observed in the first path.

For two young subjects ( Fig. 1 B), the TCOP moved toward the anterior part of the stance foot. These subjects started to rise and initiated their forward displacement on both feet. Progressively the stance leg became dominant to perform simultaneously rising and gait initiation. In a previous study, Magnan et al. defined this path as a strategy related to gait initiation . It can be assumed that the forward projection of the body was compensated by the gait initiation and the toe-off of the first step. It is likely that this strategy requires an efficient control of balance. Indeed, we observe that elderly did not use this strategy, probably because it is too demanding in balance control.

Nevertheless, in our study, a third observation was never described in the literature (youth Fig. 1 C). At the start of the rising, the TCOP shifted rapidly sideways toward the support leg. Rising and forward displacement were then performed with the single support leg and gait seems to be initiate very early, before the standing position. This behavior was also observed only in young subjects. An excellent balance control and an optimal muscle function, especially at the level of knee extensors, may explain that, in our study, elderly did not prefer this behavior. A detailed analysis of the ankle and knee moments and electromyography of leg muscles should be helpful to better understand this rapid shift towards the stance foot.

Finally, for two elderly subjects ( Fig. 3 B), the initial backward shift of the COP was probably related to difficulties in rising from the chair. We learned later that these patients have subsequently developed a backward postural disadaptation syndrom.

This study has several limitations that must be reported. First, the number of subjects is too small in the young group especially as we observed three different behaviors. For this reason, it is not correct to call our observations “strategies”. Further studies including full motion analysis (kinematics, dynamics and electromyography) will be necessary to clarify our observations. Moreover, even if we have noticed in the inclusion criteria the level of physical activity (moderate in young people and autonomy in daily life in elderly), we omitted the history in terms of physical activity. Indeed, it would not be surprising to find postural changes due to past high-level sport practice, a parameter that could be taken into account in future investigations.

In conclusion, the study of the COP during STW task seems to be useful to observe different ways of rising. It would be interesting to continue work in this direction to validate this tool to estimate postural behavior during the rising in elderly and to detect possible risk of fall. More work is required to improve our understanding of strategies during STW tasks, especially analyses of center of mass path, forces and moments at the joints.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sylvie Nadeau (REPAR) for helpful discussion about this project.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Se lever d’une chaise fait partie des tâches habituelles de la vie quotidienne. La capacité à se lever en toute sécurité tend à décliner avec l’âge, et le transfert assis-debout fait partie de différents tests cliniques permettant d’évaluer l’équilibre postural chez la personne âgée . Plusieurs études sur la tâche de transfert assis-debout ou « Sit-to-Stand » (STS) ont analysé les paramètres biomécaniques et physiologiques chez les sujets jeunes et les sujets âgés . Néanmoins, dans la vie courante se lever d’une chaise est communément suivi d’un déplacement . Ainsi, la tâche de transfert assis-marche ou « Sit-to-Walk » (STW) apparaît plus fonctionnelle. Elle a été étudiée chez le sujet jeune , le sujet âgé , les patients post-AVC et les patients Parkinsoniens . Tous les auteurs confirment que cette tâche requiert une maîtrise posturale plus importante que pour le transfert STS.

Chez le sujet sain, deux stratégies liées respectivement à la stabilité posturale et à l’initiation de la marche ont été identifiées . Pour la première stratégie, le centre de pression global (CdPG) localisé initialement entre les deux pieds, rejoignait latéralement le pied d’appui, par contre pour la deuxième stratégie, le CdPG rejoignait en diagonale la partie antérieure du pied d’appui . Les auteurs sont arrivés à la conclusion que l’initiation du pas intervenait plus précocement dans la deuxième stratégie .

Les patients parkinsoniens ou les sujets âgés ayant peur de chuter semblent avoir des difficultés dans le transfert STW et donc divisent la tâche en deux parties : transfert assis-debout puis transfert debout-marche . Cette stratégie permet de faciliter la stabilité posturale avant l’initiation de la marche qui survient plus tardivement . Cet enchaînement permet de diminuer le risque de chute pendant la réalisation du STW.

L’analyse des déplacements du CdPG montre son intérêt dans l’identification de certaines stratégies pendant le STW, mais à ce jour une seule étude décrit le déplacement du CdPG durant le STW chez le sujet jeune en bonne santé . L’objectif de cette étude était d’étudier les déplacements du CdPG pendant le STW chez le sujet jeune et âgé. Puisque la personne âgée semble initier la marche plus tardivement que le sujet jeune, nous avons émis l’hypothèse que cette différence serait visible sur les trajectoires du CdPG.

2.2

Méthodes

2.2.1

Population

Neuf adultes jeunes en bonne santé (5 hommes et 4 femmes, âge moyen : 24 ans ± 3,4) et 19 sujets âgés en bonne santé (6 hommes et 13 femmes, âge moyen : 74,2 ans ± 5,9) ont participé à l’étude. Dans le groupe de personnes âgées, aucun participant ne présentait de troubles neurologique ou musculaire, de problème de marche ou d’équilibre. Les sujets de ce groupe vivaient à leur domicile et étaient indépendants dans les activités de la vie quotidienne. De plus, ils ne souffraient d’aucune déficience chronique associée à une pathologie neurologique, rhumatologique ou orthopédique et d’aucune maladie chronique ou aiguë avec syndrome inflammatoire. Enfin, aucun participant ne souffrait de troubles psychiatriques ou de démence. Tous les participants pouvaient se lever et marcher sans aide.

Dans le groupe de sujets jeunes, aucune pathologie musculaire, neurologique ou orthopédique n’était rapportée. Tous les sujets jeunes étaient actifs et pratiquaient une activité physique régulièrement mais pas à un haut niveau ni en compétition.

L’étude a été approuvée par le Comité régional de protection des personnes (CPP) et le consentement des participants a été recueilli.

2.2.2

Instrumentation

Pour le groupe de sujets jeunes, deux plateformes de force (AMTI, Advanced Mechanical Technology, Inc., Watertown, États-Unis) ont été utilisées pour enregistrer et digitaliser (1 KHz) les trois composantes de la force résultante de réaction au sol (FRS). Pour le groupe de sujets âgés, nous avons utilisé des semelles F-Scan (Tekscan, Inc., South Boston, États-Unis) pour enregistrer la pression plantaire des deux pieds et la FRS verticale. Nous avons suivi les procédures de calibration du constructeur pour les deux systèmes utilisés. Comme décrit dans la littérature , la corrélation entre les paramètres enregistrés par les deux systèmes apparaît suffisamment satisfaisante pour qu’une comparaison des mesures, effectuées en respectant strictement les recommandations d’usage, puisse être réalisée.

2.2.3

Déroulement du test

Les sujets étaient assis sur un tabouret avec les bras croisés sur la poitrine et chaque pied sur une plateforme de force. Afin de minimiser l’influence de la taille du sujet, nous avons mesuré la longueur de la jambe en partant du condyle latéral fémoral jusqu’au sol et ajusté la hauteur du siège à 100 % de cette longueur. Les instructions étaient : « Au signal “Go”, marchez à une vitesse confortable jusqu’au repère situé 5 mètres plus loin ». Afin de respecter la nature propre du STW, il n’était fait aucune mention de la nécessité de se lever avant de marcher. Chaque participant effectuait 5 essais.

2.2.4

Analyse des données

Pour chaque pied, le centre de pression (CdP) correspond au point d’application de la force résultante de réaction au sol (FRS). Les deux plateformes de force et les semelles baropodométriques fournissaient les mesures du CdP. En utilisant la position du CdP sous chaque pied et la composante verticale de la FRS, nous avons calculé le CdP global (CdPG), c’est-à-dire le barycentre des deux CdP. Les déplacements du CdPG dans le plan horizontal (axe antéropostérieur [AP] et axe médio-latéral [ML]) étaient analysés du début du lever jusqu’au décollement des orteils de la jambe oscillante. Le début du lever correspondait au moment où la force verticale dépassait la force verticale moyenne calculée au cours des 200 premières millisecondes de l’enregistrement + 2 écarts-types. La fin du lever correspondait au moment du décollement des orteils de la jambe oscillante, quand la force sous le pied oscillant était égale à zéro.

Les signaux moyens (forces et déplacements) étaient déterminés à partir des 5 essais.

Pour l’analyse statistique, nous avons utilisé le logiciel SPSS Statistics 19 (IBM Corporation, États-Unis). Après vérification de la normalité de la distribution des variables, nous avons comparé les moyennes à l’aide d’une analyse de variance Anova à un facteur et du test post-hoc de Scheffé. Le résultat était considéré statistiquement significatif quand p < 0.05.

2.3

Résultats

2.3.1

Déplacement du CdPG chez les sujets jeunes

Au début du lever, le CdPG était le plus souvent situé près de la ligne joignant les chevilles à mi-distance entre les pieds. Une première période était définie entre le début du lever et le moment où la force verticale sous le pied oscillant atteignait sa valeur maximale (PV ou pic de force verticale). Ensuite, nous avons observé une seconde période, allant du PV au décollement du pied oscillant. Durant cette deuxième période, le CdPG se déplaçait vers le pied d’appui.

Nous avons observé plusieurs types de déplacements du CdPG ( Fig. 1 ).