Fig. 39.1

An MRI on a left knee showing a cartilage lesion on the medial femoral condyle. See arrow

39.2.1.4 Technetium Scintigraphy

In chronic medial knee pain, increased tracer uptake in bone scintigraphy is more sensitive for medial knee pain than bone marrow oedema pattern on MRI. Scintigraphic examination could be used when patients after trauma do not show any significant injury on MRI while still in considerable pain [12, 13].

Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) [14] could be used to assess the physiology and homeostasis of subchondral bone adjacent to untreated and treated articular cartilage defects.

39.3 Operative Interventions

39.3.1 Arthroscopy

Despite significantly improved detection with MR, still arthroscopy evaluation is the gold standard.

However, even arthroscopy has its limitations [15].

When we have a patient with disturbed joint function and pain and is planning an arthroscopy, first of all, we need to classify the lesions to:

Furthermore, the surgeon should try to find out the aetiology of the lesion. Is it a lesion due to trauma and is it acute or and elderly lesion, chronic lesion? The cartilage lesions should also be evaluated in relation to concomitant injuries such as ligament injuries, meniscal damage and sinusitis.

Use a standard arthroscopic probe to examine the joint surface to determine cartilage quality. The surgeon needs to carefully palpate fissures and tissue surrounding defect to determine integrity of surrounding cartilage. Using a graduated probe, measure the anterior-posterior and medial-lateral dimensions of each defect.

To decide what kind of treatment to choose, the surgeon needs to estimate:

1.

Patients’ age and activity level

2.

The degree of pain and disability that the patients are experiencing

3.

Location of cartilage lesions and the size and depth of cartilage lesions

4.

Coexisting joint pathology such as loss of meniscus, ligament insufficiency, bone loss and malalignment

5.

Other concomitant diseases

Furthermore, the following must be considered:

Typically, the patients to treat are those with symptoms of pain, swelling and catching/locking and with the following appearances [16, 20]:

Isolated cartilage defects ICRS grades 2–4 > 1 cm2 on weight-bearing surfaces

Cartilage defects with concentrated high uptake of technetium at the lesion size or similar with long-standing concentrated bone marrow oedema

Related to studies, early treatment of those lesions might be important for a more successful outcome.

ICRS grade 1 lesions are superficial fissures and cracks and need no treatment.

ICRS grade 2 lesions down to less than 50 % cartilage depth are often unstable, with partly detached fragments that need to be debrided to form stable lesions. The prognosis for ICRS-2 partial-thickness lesions seems good with diminished mechanical symptoms following a simple debridement that involves excision of the unstable cartilage fragments back to smooth edges and leaves the base intact [16, 20].

In the literature, the deep to bare-bone lesions seem troublesome [21]. Lesions that extend through >50 % of the cartilage thickness are classified as ICRS-3 a–d. While debridement of unstable edges (as is suggested for ICRS-2 lesions) is suitable for ICRS-3 lesions, further treatment is recommended for these more extensive lesions [20].

39.3.2 Cartilage Defects with Concomitant Joint Injuries

Cartilage lesions that are found together with other injuries have to be related to the severity of the other injury/injuries. If the cartilage lesions are suspected to be part of the symptomatology, they are treated the same way as the isolated lesions.

If instability is the major symptom from an ACL-deficient knee with small- to medium-size cartilage lesion without subchondral reaction, such a lesion may be left untreated.

If, however, the joint besides the ACl injury also has a major loss of the menisci and a cartilage lesion with instability and pain, the evaluation and decision is more difficult. Without damaged cartilage, such a knee joint might function well without ACL reconstruction and meniscal grafting. Instead, with all three areas destroyed, the joint is in danger to develop into OA. In such a situation, the cartilage lesion treatment may need to be supported by the meniscal and ACL grafting at the same time for a maximal protection of injured articular joint [23, 24].

39.4 Treatment Strategy

The prevalence of focal articular cartilage lesions among athletes is higher than in the general population [25]. Furthermore, the treatment goals differ considerably between the professional and recreational athletes. The high costs for the sports activities and involved professional clubs and the short duration of a professional career influence the treatment selection for the professional athlete with less influence in recreational sports.

Treatment goals also differ between recreational and professional sports players. Recreational players mostly hope for a relief of pain, return of functionality and, if possible, some sports participation, while professional players need a fast return to their previous, high-demanding, activity level without any delay. In the literature of reported results, ACI and osteochondral autografts seem to lead to a better structural tissue repair, and such a repair would be of interest to be able to perform at top again after trauma [26–28].

But in spite of such facts, ACI and OAT are not the treatments of first choice among professional athletes.

39.4.1 The Operative Alternatives

39.4.1.1 Microfracture and Other Bone Marrow Stimulation Techniques

Due to the long rehabilitation time after ACI, microfracture is most often considered the first treatment option among professional sportsmen. In studies, microfracture has shown a statistically significant improvement from baseline in functional outcome, pain scores and Tegner activity levels after at least 1-year follow-up among professional football (soccer) players and other athletes [29]. Furthermore, the technique is fairly easy to use and cheap. Microfracture can also be used in combination with scaffold augmentations such as variants of AMIC (membrane protecting the microfractured area) [30] and scaffolds for cell ingrowth like Hyalofast [31] and blood clot augmentations (BST-CarGel) [32]. Different synthetic porous cylindrical grafts [33–35], biomimetic multilayer grafts [36] and BMAC (bone marrow aspirate concentrates) [37] are also possible but less useable for high-level sportsman.

39.4.1.2 Osteochondral Grafts

The osteochondral autograft transfer technique (OAT) showed superior clinical results compared to microfracture in a randomised study among both professional and recreational athletes [38]. Also, prospective case series show good clinical results up to 17-year follow-up in a mixed athletic population [39]. To use osteochondral grafts (OAT), having a shorter mean rehabilitation time compared to both microfracture and ACI could also be an alternative instead of microfracture when a short rehabilitation time is of interest. The technique is fairly cheap but may be difficult to use transarthroscopically as not all lesions reachable by microfracture could be treated by OAT.

39.4.1.3 ACI

ACI showed an improvement from baseline in functional outcome and pain scores and an even higher good to excellent treatment success in professional football (soccer) players and adolescent athletes compared to microfracture (66–83 % for microfracture vs. 72–95 % for ACI). Also, Tegner activity levels were significantly higher after ACI in football (soccer) players [42, 43]. The negative part for the athlete is the long rehab time needed.

If ACI is the treatment of first choice, a surgical debridement of injured cartilage area with an additional cartilage biopsy may be indicated to relieve symptoms during the ongoing series. The implantation may then be planned after the patient’s wishes and related to the seasons (Fig. 39.2).

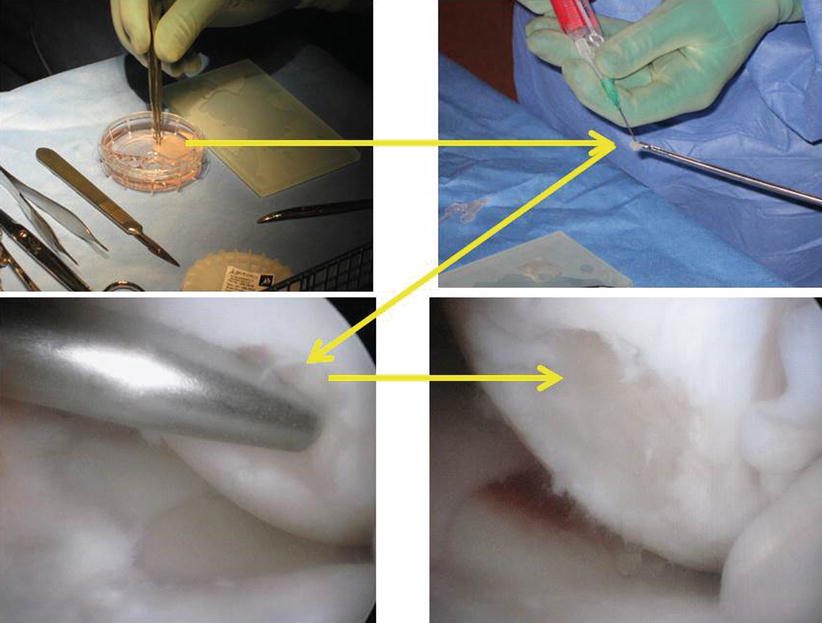

Fig. 39.2

The cartilage lesion in Fig. 39.1 is treated by transarthroscopic ACI with hyaluronan cell-seeded scaffold

An interesting alternative is the fourth-generation ACI with fragmented cartilage implanted under a resorbable membrane (CAIS). The technique can be done in one stage, but the rehab time is equal compared to first- to third-generation ACIs [40, 41].

Mithoefer et al. showed that the average time to return to professional sports is highest after ACI (18 ± 4 months; range, 12–36 months) compared to microfracture (8 ± 1 months; range, 2–16 months) and OAT (7 ± 2 months; range, 4–11 months) [26].

39.4.2 Non-biological Local Repairs

39.4.3 General Comments

For professional football (soccer) players and other high-level athletes with symptoms <12 months, Mithoefer et al. found a better clinical outcome and greater return to sports after microfracture as well as ACI [42, 43].

Also, when treated with OAT, the chronicity of the lesion seemed important on clinical outcome and return to sports.

From the sportsman’s point of view, microfracture or variants of transarthroscopic bone marrow stimulation techniques are reasonable choices as they are safe and simple techniques and allow careers to continue for some more years. During the operative procedure, it is important to fast stabilise the fragmented cartilage defect. A cartilage biopsy may be taken for a future ACI.

The other alternative is an osteochondral graft related to the faster rehab time compared to microfracture. However, it is important to remember that with focal lesions >2 cm2, microfracture and OAT showed significantly worse clinical outcomes and a lower return to high-level sports when compared to lesions <2 cm2 [28].

In contrast, with ACI, no influence on lesion size and clinical outcome or return to sports participation has been found, which indicates that for larger lesions, ACI is the treatment option of first choice for both professional and recreational sports athletes [28].

39.5 Rehabilitation and Return to Play

A return to the preinjury sports activity level is much more important when dealing with high-level athletes compared to the recreational sportsmen. However, in today’s community more and more people are active at higher and higher ages. The activities for the recreational people are also more demanding, meaning that also recreational sportsmen have high demands on their joint restoration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree