Chapter 15 Bone Grafting around an Articular Joint

Introduction

The contribution of stem cells in the graft is thought to be small, but the scaffold of bone and its contained growth factors is ideal for the formation of new bone. William Macewen of Glasgow proved the ability of bone graft to regenerate a humerus, and this followed an exemplary series of studies and research.1

The early hematoma forming around an injured bone surface (whether the result of your osteotomy or a fracture) immediately contains stem cells.2 These multiply rapidly in the hematoma and are in the right place to contribute to healing.

The osteoblasts are particularly sensitive to the mechanical environment.

Stability is defined as the maintenance of reduction and correlates with strength. Stiffness is a distinctly different parameter from strength and in fracture or osteotomy fixation is defined as the rigidity of the construct.

Flexible fixation and early cyclic movements are appropriate for the bulky callus formation needed in diaphyseal fractures.3

This external callus is rarely needed in the metaphysic or epiphysis where there is sufficient bulk and well vascularized cancellous bone that will allow rapid union. John Charnley took biopsies at 6 weeks following knee arthrodesis to prove that union is achieved in this time.4

Taking Autograft

Cancellous Graft

When possible, a small sandbag behind the hip is useful.

Cut the fibers of gluteus maximus as they arise from the lip of the iliac crest.

Hemostasis will be needed at the posterior part of your incision.

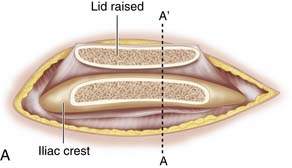

Use a saw to cut the outer table of the iliac crest and then a broad osteotome to lift a lid. This exposes the cancellous layer (see Fig. 15-1, A-C).

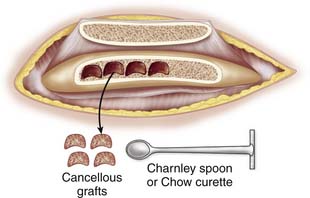

Use a sharp, long-handled curette to remove cancellous bone from between the cortical sheets (Fig. 15-2).

Keep the hematoma that gathers in the wound with your graft.

Corticocancellous Strips

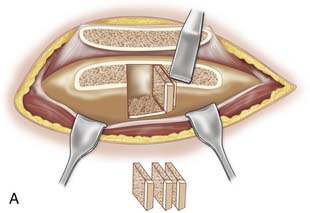

Expose the iliac crest as explained earlier. Use the saw to make an initial vertical cut, and then use a narrow and thin osteotome or chisel to cut thin vertical strips. A hammer is actually safer for controlling the instrument, as it avoids plunging that can occur if an osteotome is pushed by hand (see Fig. 15-3, A-B). The saw can also be used to cut the strips.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree