Bone Anchors

Thomas A. Brosky II

Michael C. McGlamry

Mitzi L. Williams

Many surgical procedures require attachment or reattachment of tendons and ligaments to bone. A secure attachment of soft tissue to bone remains essential for stability and function of the lower extremity. This chapter reviews the indications of bone anchor use in foot and ankle surgery. Several types of bone anchors are discussed. The models and companies continue to change as medicine advances; the concepts, however, remain the same.

PRINCIPLES

Soft tissue attachment procedures have been classified into two main groups: natural and mechanical (1). Even with advanced technology, these concepts have remained the same.

The natural group can be defined as attachment of soft tissue to bone, with the use of suture. Typically, this involved a double-armed suture technique to grab the target soft tissue. These sutures were then passed through drill holes in the bone. Terminal attachment of tendon to bone historically was done using a trephine or larger drill hole with two divergent communicating smaller holes to allow passage of the suture to tension the tendon into the bone “tunnel.” Bone plugs can also be utilized for adjunctive stability, thus taking strain off of the sutures and preventing slippage. Effectively this type reinforcement was the early predecessor to today’s interference screws. One example of direct suturing of soft tissue to bone that is still frequently employed today is the suture reinforcement of the tibialis anterior transfer as part of a McGlamry Young medial arch tenosuspension, thus preventing shift or displacement of the transferred tendon from its groove.

With both natural and mechanical techniques, proper tensioning of tendons and ligamentous structures is crucial. It can be challenging to achieve and assess proper tension for optimal function. Inadequate tension can lead to flaccid tissue with a decrease in function. Alternatively, excessive tension can create further deformity with improper function and increased potential for failure of the reattachment point or rupture of the tendon.

Historically, mechanical methods of establishing a stable bone-soft tissue interface employed the use of screws, staples, and unspecified metallic and nonmetallic fixation devices (Fig. 80.1). In more recent history, anchors have been designed to promote stability and simplify reattachment of soft tissues to their osseous substrate. Careful selection of an anchoring device should be part of the preoperative planning. Evaluation should include a consideration of stability principles, anticipated load, anatomic location within cortical or cancellous bone, bone density, patient benefits, and cost.

Further decision making will include absorbable versus nonabsorbable types of devices. Collectively, these factors assist with product selection.

Device selection should also include any history of allergies to components of the anchor device itself.

TYPES OF BONE ANCHORS

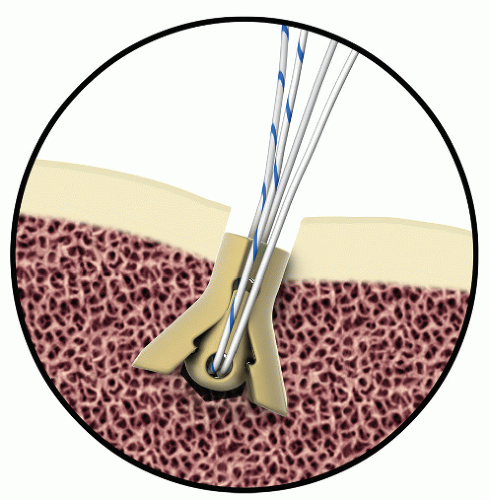

Today’s anchors are available in many shapes and sizes, metallic and nonmetallic. The nonmetallic variety is available in absorbable and plastic constructs. New devices are constantly being developed and improved (2) (Fig. 80.2).

Available anchors can be divided into several categories: barbed or winged devices, press-fit devices, and screw-in devices. Additionally, there are a few newer devices that seemingly occupy a hybrid category possessing operational characteristics of several types and being fabricated of shape memory materials or polymers.

Screw-in anchors were one of the first types available. They are available in many sizes and materials and from most manufacturers. Application is straightforward and may be performed manually or with power instrumentation. Once the anchor has been delivered flush to the bone, the attached sutures are utilized to advance the target tissue flush to the previously prepared bone surface (Fig. 80.3).

Barbed anchors are another of the earlier type designs. These devices are manually impacted into the bone. As the anchor is advanced, the barbs are compressed in toward the body of the device. Once in place, a pullback on the sutures insures that the barbs are deployed and locked into the cancellous bone (Fig. 80.4).

Winged anchors deploy their legs in a fashion similar to the barbed anchors, but instead of barbs or hooks, employ a flatter blade “foot,” which gives a larger surface area and therefore generally provides greater resistance to pullout. These anchors are akin to a molly bolt (Fig. 80.5).

In the smaller sizes, many of the anchors are press fit and generally fabricated of a polymer construction. These are placed into a slightly undersized hole where the teeth on the sidewalls and coefficient of static friction resist pullout of the devices (Fig. 80.6).

Several devices on the market offer the advantage of knotless application. This may provide an advantage in allowing various mechanisms of locking the suture at the desired tension without the variability and potential weakness and prominence of the surgeon’s knot stack.

Knotless technology takes several forms. One particular device that dramatically changed arthroscopic rotator cuff repair employs a crimping mechanism to lock the position of the suture inside the anchor after the desired tension is dialed into the sutures though the anchor (Fig. 80.7).

Some of the newest devices employ a dual D ring-type design that allows slide tightening of the suture through the anchor yet resists sliding in the reverse direction (Fig. 80.8).

INTERFERENCE ANCHORING DEVICES

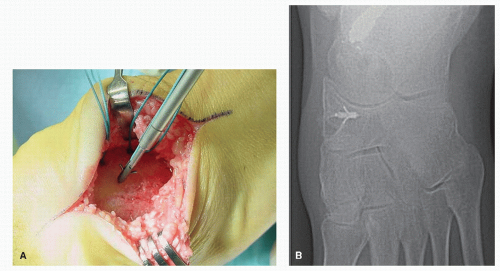

Other than the traditional devices that allow a device implanted into the bone with some eyelet-type technology to allow for the

suture to pull the soft tissue to the bone, other devices with a screw-type design allow the target soft tissue to be introduced into a bone tunnel and then trapped there with an interference screw. As with other devices, they are available in absorbable and metallic varieties. One big advantage of these devices is that they allow for retensioning of the soft tissue if the surgeon is not satisfied with tension achieved after initial placement of the screw. The screw is simply backed out and the tendon tension repositioned within the tunnel and the screw reinserted. These devices have allowed for new techniques in ligament reconstruction utilizing allograft with these devices to recreate the previously compromised natural tissues without requiring harvest of autogenous local tissues and compromise to these donor sites (Fig. 80.9).

suture to pull the soft tissue to the bone, other devices with a screw-type design allow the target soft tissue to be introduced into a bone tunnel and then trapped there with an interference screw. As with other devices, they are available in absorbable and metallic varieties. One big advantage of these devices is that they allow for retensioning of the soft tissue if the surgeon is not satisfied with tension achieved after initial placement of the screw. The screw is simply backed out and the tendon tension repositioned within the tunnel and the screw reinserted. These devices have allowed for new techniques in ligament reconstruction utilizing allograft with these devices to recreate the previously compromised natural tissues without requiring harvest of autogenous local tissues and compromise to these donor sites (Fig. 80.9).

Figure 80.2 Artist rendering of newer design polymer anchor. As suture is loaded, the anchor legs expand, increasing anchor hold. (Courtesy of MedShape Solutions, Inc.) |

Figure 80.3 Radiograph demonstrating corkscrew-type anchor placed for reattachment of the Achilles tendon. |

ADVANCED SUTURE BUTTON DEVICES

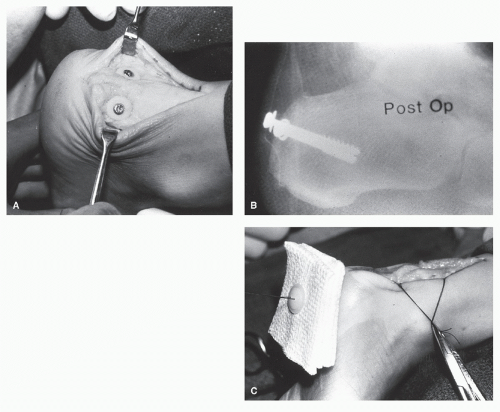

Over the last several years, there has been a family of devices coming to the market that have allowed a toggle and button design to

be applied to compress two bones together. Typically employing multiple passes of heavy gauge braided nonabsorbable suture, these devices allowed for some physiologic play while still maintaining tight approximation. Initially, these devices were applied to syndesmosis repairs of the ankle. As a result of the play intrinsic to the device, the need for removal, as was typically required with syndesmotic screws, no longer existed (Fig. 80.10).

be applied to compress two bones together. Typically employing multiple passes of heavy gauge braided nonabsorbable suture, these devices allowed for some physiologic play while still maintaining tight approximation. Initially, these devices were applied to syndesmosis repairs of the ankle. As a result of the play intrinsic to the device, the need for removal, as was typically required with syndesmotic screws, no longer existed (Fig. 80.10).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree