Bacterial Arthritis

Arthur Kavanaugh

Maika Onishi

Introduction

Bacterial arthritis is a true rheumatologic emergency that can lead to irreversible joint destruction, increased morbidity, and accelerated mortality, without prompt diagnosis and treatment. Although many infectious agents may cause arthritis, bacterial arthritis is the most significant because of its rapidly progressive and highly destructive nature. Despite recent advances in antimicrobial therapy, diagnostic testing, and general medical care, the prognosis for patients with bacterial arthritis continues to be guarded with 25% to 50% of patients suffering permanent joint damage and an estimated 5% to 15% case fatality secondary to complications including sepsis. Perhaps the most important factor regarding the outcome of patients with bacterial arthritis is the speed with which appropriate therapy is instituted. Therefore, it remains true

at the start of the new millennium as it has for more than half a century; clinical suspicion of the diagnosis of bacterial arthritis is the most critical consideration for the clinician.

at the start of the new millennium as it has for more than half a century; clinical suspicion of the diagnosis of bacterial arthritis is the most critical consideration for the clinician.

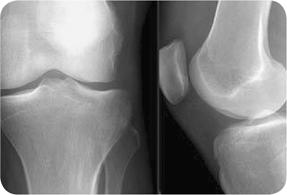

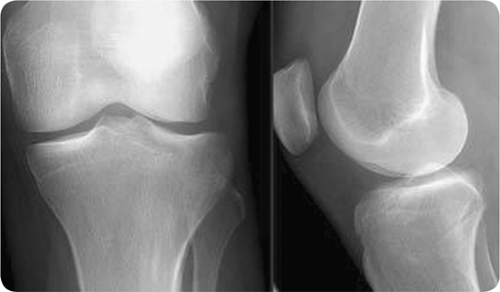

Figure 23.1 Plain radiograph of septic arthritis. Medial and lateral x-rays of the left knee showing mild joint effusion, but is otherwise normal. |

Bacterial arthritis ensues when foreign organisms invade the synovium or joint space. In the majority of cases, infection is introduced via hematogenous spread from a distant site. Less commonly, bacterial pathogens reach the joint space via direct inoculation through a penetrating trauma or procedure (e.g., arthrocentesis, surgery) or via contiguous spread from adjacent soft-tissue or bone infections, including cellulitis, osteomyelitis, and bursitis. Upon entry into the joint space, bacteria induce an acute inflammatory response, which rapidly progresses to synovial hyperplasia and infiltration by inflammatory cells. Without prompt treatment initiation, this can lead to enzymatic and cytokine-mediated cartilage and bone degradation within days. Additionally, in bacterial arthritis, the urgency of treatment is further heightened because of potential infection with bacterial strains with virulence factors (e.g., toxins, adhesins), which are associated with increased pathogenicity and disease severity (1).

The two major classes of bacterial arthritis are nongonococcal and gonococcal arthritis (discussed below), with nongonococcal arthritis accounting for the majority of cases across all age and risk groups. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common organism infecting naïve joints in 60% to 70% of cases. Because it is such a frequent cause of bacterial arthritis, the increasing prevalence of community- and hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staph. aureus (MRSA) is an important consideration when initially treating bacterial arthritis. Additionally, staphylococci infections are associated with higher rates of fulminant disease and residual joint damage, thus necessitating prompt diagnosis and aggressive treatment.

The main remaining causes of bacterial arthritis include streptoccci, gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobes. Host–pathogen associations may be helpful in guiding initial antimicrobial treatment. Streptococci (e.g., Streptococcus viridans, Strep. pneumoniae, group A and B streptococci) account for 15% to 20% of nongonococcal arthritis and may be preceded by primary skin or soft-tissue infections. Group A streptococci are the most common streptococcal species and are often isolated after dental procedures. Gram-negative bacilli infections (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis) are responsible for 5% to 25% of cases, and are associated with chronic systemic illness, immunosuppression, intravenous drug use, and advancing age (e.g., in elderly patients). These infections may begin as urinary tract or skin infections with subsequent hematogenous spread to a joint. Lastly, anaerobic bacteria (e.g., Bacteroides, Clostridium, Fusobacterium) account for 1% to 5% of bacterial arthritis, although this may be an underestimate as anaerobes have historically been more difficult to isolate. While most bacterial arthritis infections are monomicrobial, anaerobic infections may be polymicrobial in nature. Predisposing factors include diabetes mellitus, immunocompromised states, and postoperative wound infections. Suspicion for an anaerobic agent should be raised in the case of foul-smelling synovial fluid or plain radiographs depicting gas in the joint space. Adequate drainage of the joint is a key adjunct to antimicrobial therapy in the case of anaerobic infection.

Less commonly, other organisms may also be associated with bacterial arthritis. One worth mentioning is the Brucella species (e.g., B. melitensis), which is becoming more prevalent worldwide (2). Risk factors include consumption of unpasteurized milk or cheese or direct contact with infected animals. Presentation is usually characterized by monoarthritis of the hip or knee, although oligoarthritis, sacroiliitis, or spondylitis may also be seen. Further work-up should be guided by the clinical setting if one of the common etiologic agents is not identified.

Gonococcal arthritis is the most common cause of bacterial arthritis in young, sexually active individuals without a history of joint disease. Women

are at greatest risk for disseminated gonococcal infection, especially during pregnancy and menses, and are affected two to three times more often than men. While, overall, the prognosis for gonoccocal arthritis is better than that for nongonococcal arthritis, rapid diagnosis is equally important in this setting given the potential for joint destruction with delays in treatment.

are at greatest risk for disseminated gonococcal infection, especially during pregnancy and menses, and are affected two to three times more often than men. While, overall, the prognosis for gonoccocal arthritis is better than that for nongonococcal arthritis, rapid diagnosis is equally important in this setting given the potential for joint destruction with delays in treatment.

Diagnosis of gonococcal arthritis can be difficult, as only 25% of patients may recall signs of mucosal involvement of the urethra, genitalia, or rectum. Clinical suspicion should be raised in the setting of purulent monoarticular arthritis, as well as in the setting of arthritis–dermatitis syndrome, the typical presentation of gonococcal arthritis in 60% of cases. It is characterized by a triad of migratory polyarthritis, tenosynovitis, and dermatitis. At disease onset, patients commonly experience migratory arthralgias in the upper extremities (e.g., wrist, elbows) and, less frequently, in the lower extremities. Later, patients may develop tenosynovitis, a finding not commonly seen in infectious arthritis related to other organisms. Gonococcal tenosynovitis most often occurs in the dorsum of the wrist, hand, or ankle. The skin lesions of disseminated gonococcal infection are typically painless, nonpruritic, maculopapular lesions distributed over the distal extremities, especially the palms and soles.

Diagnosis of gonococcal arthritis is further complicated by the difficulty in isolating gonococci in synovial fluid and blood. Even with attention to proper culture technique (e.g., chocolate agar, rapid plating), gram stains and cultures of synovial fluid are positive in fewer than 40% of cases, and blood cultures are almost always negative (3). Mucosal cultures of the urethra, pharynx, cervix, and rectum should be performed in all patients, since they have a higher yield and may be positive even in the absence of symptoms. More sensitive techniques for identification of gonococci, such as polymerase chain reaction, are currently not routinely used, but may provide additional diagnostic value in the future.

Although most patients respond dramatically to antibiotics within 24 to 48 hours and nearly all make a complete recovery, when gonoccocal arthritis is suspected, patients should be considered for hospital admission to confirm diagnosis, exclude complications such as meningitis and endocarditis, and receive parenteral therapy.

Clinical Points

Clinical suspicion of the diagnosis of bacterial arthritis is the most important consideration for the clinician.

Extensive, rapid joint destruction may occur without prompt initiation of appropriate antibiotics.

Acute monoarticular arthritis should be considered bacterial arthritis until proven otherwise.

Joint drainage and antibiotic therapy are the key components of treatment.

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common organism across all ages and risk groups, while Neisseria gonorrhoeae accounts for most cases among young, sexually active individuals.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical suspicion for bacterial arthritis should be raised in patients with underlying joint disease, compromised immune function, and increased infection risk, all of which are key risk factors for joint infection. Joints that have been damaged by arthritis (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, crystalline arthritis) or trauma are more susceptible to infection than normal joints. This may be secondary to structural damage, neovascularization, or local factors. As the synovium serves an important protective role in joint defense, patients with rheumatoid arthritis are particularly susceptible. Patients with impaired host defenses because of extremes of age, systemic illness (e.g., diabetes mellitus, malignancy, liver or kidney disease), immunosuppressive medications, or immunocompromised conditions (e.g., HIV/AIDs) are also at increased risk. Likewise, it follows that risk factors for infection such as prosthetic joints in which foreign bodies serve as a nidus for infection, intra-articular joint injections, skin infections, and intravenous drug abuse may predispose patients to bacterial arthritis. As a clinician, obtaining a thorough history regarding these risk factors plays an important role in diagnosis and treatment.

Examination

The classic presentation for bacterial arthritis is acute monoarticular joint pain with swelling, warmth, and erythema. On examination, patients typically exhibit

obvious joint effusion, tenderness to palpation, and restricted range of motion. Large joints are more commonly affected than small joints, and in up to 70% of cases, the knee or hip is involved. Intravenous drug users may present with sternoclavicular or sacroiliac joint involvement. Fever is the most commonly associated symptom on presentation and is found in >50% of patients, while sweats and chills are less common (4).

obvious joint effusion, tenderness to palpation, and restricted range of motion. Large joints are more commonly affected than small joints, and in up to 70% of cases, the knee or hip is involved. Intravenous drug users may present with sternoclavicular or sacroiliac joint involvement. Fever is the most commonly associated symptom on presentation and is found in >50% of patients, while sweats and chills are less common (4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree