Chapter 31 Back

Cervical and Thoracolumbar Spine

Cervical Spine

Anatomy

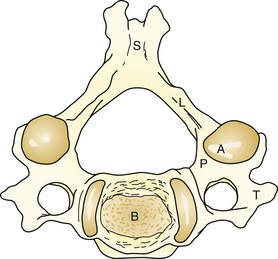

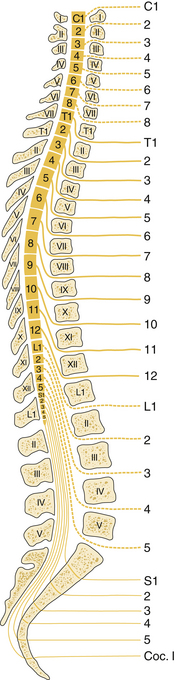

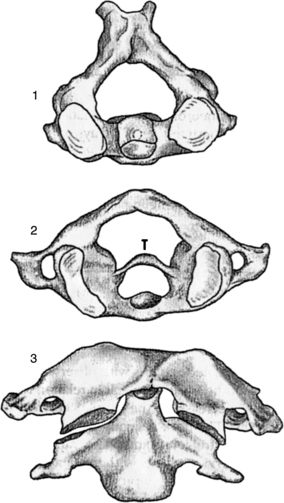

The cervical spine is made up of seven vertebrae (C1-C7). A typical vertebra has a body and neural arch. The neural arch is made up of two pedicles and two vertebrae; the laminae meet at the spinous process posteriorly. A transverse process projects out laterally on each side of the pedicle and lamina (Fig. 31-1). The articular processes on the superior and inferior parts of each vertebra at the junction of the pedicle and lamina meet at the facet joints. The first two vertebrae have distinct features. The atlas, C1, articulates with the occipital bone and has no spinous process or body. The axis, C2, has an odontoid process that articulates with C1 (Fig. 31-2); much of the rotational function of the neck occurs at this joint. C7 has a long spinous process, resulting in a palpable prominence below the skin in the lower neck.

Figure 31-2 1, Axis. 2, Atlas and transverse ligament (T). 3, Articulation of the atlas and axis.

(Redrawn from Mercier L. Practical Orthopedics, 5th ed. St Louis, Mosby, 2000, p 27.)

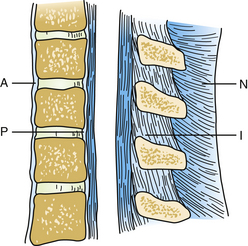

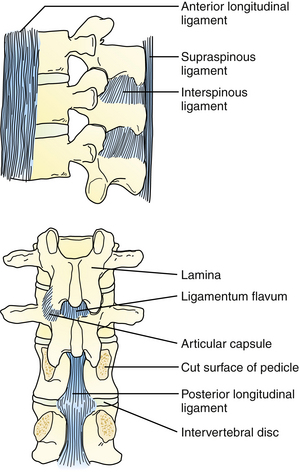

Several ligaments stabilize the neck. The anterior and posterior ligaments support the entire vertebral column (Fig. 31-3). The spinous process of each vertebra is attached by the nuchal ligament to the neck and the interspinous ligaments. Intervertebral disks separate each vertebra. Their function is to distribute the pressure over a wider area of the vertebra and allow mobility. Each disk consists of a gelatinous central nucleus and outer fibrous annulus fibrosus. Eight pairs of nerves originate from the cervical spine. The first seven nerve roots exit the spinal canal above the corresponding vertebra, and the eighth nerve root exits from below C7 (Fig. 31-4).

Physical Examination

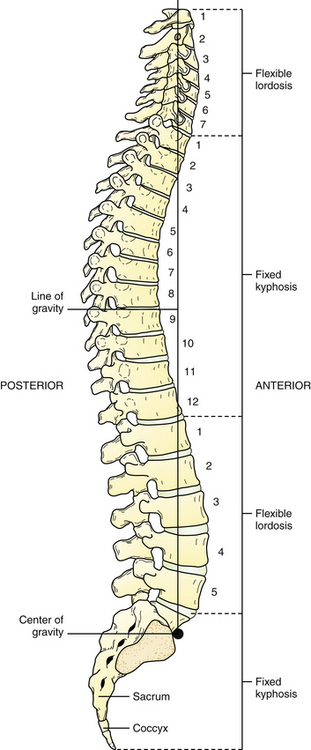

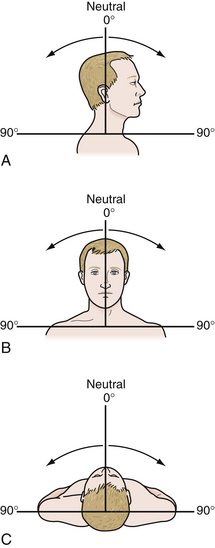

The neck examination includes inspection for any neck lesions, masses, or scars as well as posture and normal cervical lordosis, characterized by a slight anterior curvature (Fig. 31-5). The neck is palpated for points of tenderness. The range of movement is assessed by observing forward flexion with chin tilted down toward the chest and backward extension with the head tilted backward so that the eyes are looking toward the ceiling (Fig. 31-6). Lateral flexion to the right and left is the lateral bending of the neck, pointing the ear toward the shoulder on the same side. Lateral rotation to the right and left is the chin turned toward each shoulder while the head is kept upright (Table 31-1).

Figure 31-6 Range of motion. A, Flexion. B, Lateral flexion. C, Rotation.

(Redrawn from Carr AJ, Harnden A. Orthopedics in Primary Care. Newton, Mass, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1997, p 56.)

Table 31-1 Normal Range of Movement: Neck (Cervical Spine)

| Motion | Range |

|---|---|

| Flexion | 0-45 degrees |

| Extension | 0-45 degrees |

| Lateral flexion | 0-45 degrees |

| Rotation | 0-60 degrees |

Modified from Carr AJ, Harnden A. Orthopedics in Primary Care. Newton, Mass, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1997.

Examination should also include examination of the extremities. Inspection of the upper limbs may reveal muscle wasting or fasciculations. A detailed examination of the nervous system includes assessment of the power and tone of the muscles, reflexes, and sensory system, using sharp and light touch. Mapping the sensory loss by dermatomes and demonstrating asymmetry of deep tendon reflexes may show the cervical level with nerve compression. A complete general examination, including the head, neck, lower extremities, and gait, allows for evaluation of other potential causes and effects of neck problems. Specific tests to evaluate the cervical spine also include the axial compression test, which may increase symptoms of radicular pain. The distraction test may relieve radicular symptoms. Spurling’s test may produce pain on the same side as nerve root encroachment.

Torticollis

Torticollis, also called wry neck, is characterized by contraction of the sternomastoid muscle on one side of the neck, in which the head is tilted to the same side as the contracted muscle, and the chin is rotated to the opposite side. The condition may be congenital or acquired.

Cervical Radiculopathy

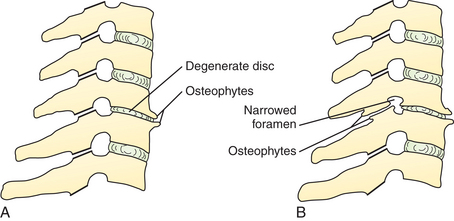

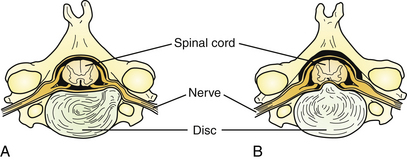

Radiculopathy occurs when nerve root compression at the neck or spine results in pain, tingling, and numbness, with or without loss of function in the area supplied by the affected nerve. Common causes of cervical radiculopathy are neural foramen narrowing, usually caused by cervical arthritis in older adults, and cervical disk lesion caused by disk degeneration or herniation. Disk degeneration results in loss of disk space, with closer approximation of the vertebrae on either side of the involved disk space and subsequent impingement on the neural foramen (Fig. 31-7). The decrease in size of the neural foramen results in nerve root compression. The C5-C6 and C6-C7 disk spaces are more often affected. Disk herniation also occurs more often in these disks (Fig. 31-8). Some of the gelatinous pulp protrudes through the annulus fibrosus at the weakest point, usually where the posterolateral longitudinal ligament crosses the disk. In a smaller disk herniation, mild local pain may be caused by pressure on the posterior ligament. A larger disk herniation may impinge on the nerve and may be posterolateral or central herniation with resultant radicular symptoms.

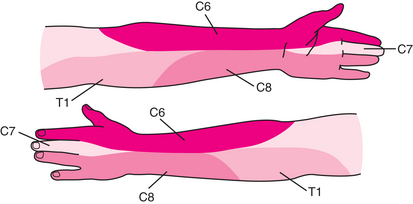

The patient has a history of pain radiating to the shoulder or down the upper extremity, which may be aggravated by coughing, sneezing, or straining; paresthesias of the fingers; and less often, weakness in the extremity. There may be a history of prior trauma. Cervical radiculopathy on examination may reveal tenderness on the neck, limitation in certain movements of the neck, focal neurologic findings such as sensory loss in the dermatome pattern corresponding to the distribution of the affected nerve root, and asymmetric tendon reflexes in the upper extremities (Fig. 31-9). General examination should include the lower extremities and gait. Axial compression testing may reproduce the pain.

Thoracolumbar Spine

Anatomy

The back is supported by 12 thoracic vertebrae (T1-T12) and five lumbar vertebrae (L1-L5). The lumbar vertebrae are larger and thicker than the cervical and thoracic vertebrae because they carry the most amount of body weight and are subject to the largest forces and stresses along the spine (see Fig. 31-5). The alignment of thoracolumbar vertebrae with their disk and ligament is similar to the cervical spine. The joints between the vertebrae, ligaments, and muscles of the back stabilize the vertebral column.

The major longitudinal ligaments connecting the vertebrae are the anterior and posterior ligaments (connect vertebral bodies), ligamentum flavum (between adjacent laminae), and supraspinous and interspinous ligaments (connect spinous processes). The anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments and supraspinous ligament run along the entire length of the vertebral column and support the spine. The interspinous ligament and ligamentum flavum provide additional posterior stability to the spine (Fig. 31-10).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree