Autologous Osteochondral Transfer for Talar Defects: Mosaicplasty

László Hangody

Ágnes Berta

INTRODUCTION

Autologous osteochondral mosaicplasty was originally developed to treat small and medium-sized (1.0 to 4.0 cm2) focal chondral and osteochondral defects of the femoral condyles and patellar trochlear surfaces. Preclinical animal studies and subsequent clinical trials since mosaicplasty was introduced into clinical practice in 1992 established the value of the mosaicplasty concept in the treatment of focal chondral and osteochondral lesions. Indication of the mosaicplasty technique was extended to talar osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) cases from the very beginning, mosaicplasty has been applied for talar OCD lesions in the author’s institute since 1992 (1,2).

Talar osteochondritis lesions are mostly caused by single or multiple traumatic events, leading to partial or complete detachment of the osteochondral fragment with or without osteonecrosis (3,4). Dislocated osteochondral fragments alter joint mechanics and cause recurrent synovitis and subsequently early ankle osteoarthritis. The OCD defects are mainly located on the medial and lateral sides of the talar dome, and less often centrally. They usually require surgical treatment, and the type of surgery depends on the size and location of the lesion, the degree of detachment, and the age of the patient (5,6). Previous therapeutical attempts may also modify the actual treatment strategy.

A great variety of surgical treatments have been developed for talar OCD lesions over the years, including lavage, debridement, removal of loose bodies, refixation, abrasion arthroplasty, anterograde and retrograde drilling, and bone grafting. Small defects and stable OCD lesions can be treated with minimally invasive arthroscopic procedures (debridement, retrograde drilling, bone grafting, etc.) (7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12). For larger osteochondral defects and unstable OCD lesions, the ultimate aim would be the long-term replacement and integration of type-specific hyaline cartilage (13).

Autologous osteochondral transplantation techniques, such as mosaicplasty, aim to produce a hyaline or a hyaline-like gliding surface over the affected area. Mosaicplasty allows creation of osteochondral autograft substitution by harvesting and transplanting cylindrical osteochondral plugs from the less-weight-bearing periphery of the patellofemoral area and inserting them into drilled tunnels in the defective section of cartilage. Use of multiple smaller grafts instead of one large block helps to avoid donor site morbidity and incongruity at the recipient site. Previous experimental trials confirmed the viability of the transplanted hyaline cartilage and fibrocartilage repair of the donor sites. Hyaline cartilage of the donor area is certainly different from talar hyaline cartilage; however, to date this fact has not been proven to have a negative influence on long-term results.

This chapter discusses the indications, contraindications, technical details, rehabilitation, pitfalls, and complications of the mosaicplasty technique when applied for the treatment of talar defects.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Preoperative x-rays, bone scan, CT scan, and MRI provide valuable information on the size and location of the lesion, blood supply of the talus, and any associated pathology (14). However, indication of mosaicplasty should be based on the size of the lesion after preparation of the recipient site. Therefore, the final decision to perform mosaicplasty is made during arthroscopic examination of the lesions, and the ideal findings for mosaicplasty are

Focal osteochondral lesion ≥10 mm in diameter

Location of the lesion on the medial or lateral dome

Detached osteochondral fragments

Otherwise normal articular surfaces of the tibia and talus

Caution should be exercised when offering mosaicplasty to

Patients over the age of 50 years

Patients with significant osteoarthritis of the ankle

Patients who have undergone multiple previous surgeries

Patients who demonstrate evidence of pan-articular arthritis or articular cartilage thinning, regardless of age or previous surgical history

As a relatively aggressive surgical treatment option (graft harvest from a healthy, asymptomatic joint; optional malleolar osteotomy for the approach; etc.), mosaicplasty is usually indicated as a second-line surgery after a failed previous surgical treatment (e.g., arthroscopic debridement, microfracture, retrograde drilling, etc.), but multiple previous surgeries should be considered as relative contraindications.

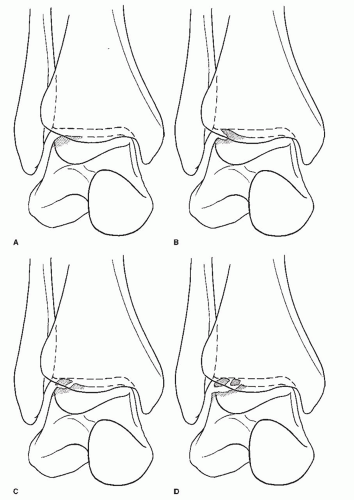

The major indication for mosaicplasty about the ankle is symptomatic grade III and IV osteochondral lesions of the talus (OLT) (Fig. 41.1). The cause of these lesions remains elusive but is related in part to trauma and ischemia. When the lesions have progressed to produce clinical symptoms of pain, locking from loose fragments, and altered mechanics, operative intervention could be considered. Mosaicplasty addresses the removal of the loose and damaged surface elements and subsequently restores the surface with contoured autogenous osteochondral plugs obtained from the supracondylar ridge of the ipsilateral femoral condyles. As experience and success are gained with OLT, there is a tendency to expand the indication to larger traumatic lesions and certain benign tumors such as unicameral and synovial cysts and enchondromas. Under these conditions, the goals and expectations need to be carefully weighed and discussed with the patient. Contraindications to mosaicplasty include sepsis, generalized arthritis, large traumatic chondral lesions that have laminated much of the talar surface, and defects related to malignancy. Additionally, avascular necrosis of the talar body cannot support graft in-growth.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Most patients with symptomatic OLT are young, are active in sports, and have been treated by a variety of conservative therapies. Many have had previous unsuccessful surgeries, including removal of loose bodies, abrasion arthroplasty, or microfracture. Marginal osteophytes, particularly of the talar neck, may be present but do not represent contraindications. As reflected in the literature, lateral talar dome lesions have a clearer link to a single traumatic event, with patients enduring symptoms for a briefer period of time than medial dome OLT. With either type of lesion, the symptoms can be acute, intermittent, or smoldering. Consequently, symptoms include sharp pain, locking, swelling, clicking, catching, giving way, and deep aching in the ankle. Associated ligamentous tears or laxity may also increase episodes of instability.

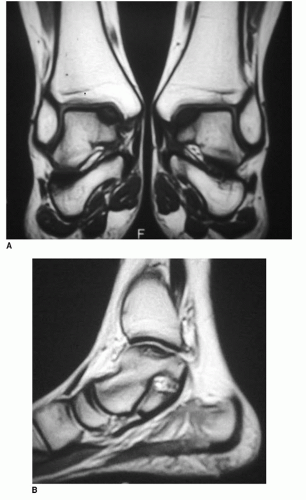

Plain film radiography can make the diagnosis of the grade III and IV OLT, while further grading of the lesion can be detailed by MRI, CT scan, and arthroscopy (Fig. 41.2). When radiographs demonstrate an OLT but the symptoms are vague, a bone scan can be helpful in determining if the lesion is actively inflamed. After an OLT has been graded as a III or IV lesion, and the symptoms are of sufficient magnitude, the option of mosaicplasty is discussed. The patient is counseled about the nature of the problem, the specifics of the surgery, the need to begin early postoperative range of motion (ROM) of the knee and ankle, and the absolute necessity of adhering to the rule of non-weight bearing for a period of time postoperatively. A concerted and controlled rehabilitation program during the first 6 postoperative months is advised.

Special attention is directed to the use of the ipsilateral knee as the donor site. The supracondylar ridge of the femoral condyle, in the absence of patellar symptoms or arthritis, remains the best source for autogenous osteochondral plugs. The quality of the cartilage closely matches the talar dome articular cartilage; the ridges offer large enough surface areas to obtain enough plugs to cover the talar dome surface; and there has been no long-term morbidity when multiple small grafts are taken. Secondary sources of grafts could be small grafts from the talar head and talar malleolar surfaces. Use of fresh allograft remains an attractive alternative but should be reserved for large defects or when there are absolute contraindications to using the femoral condyles. Consultation with a physical therapist aids the patient in understanding the need for initial non-weight bearing, ROM exercises, and use of ambulating aids.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

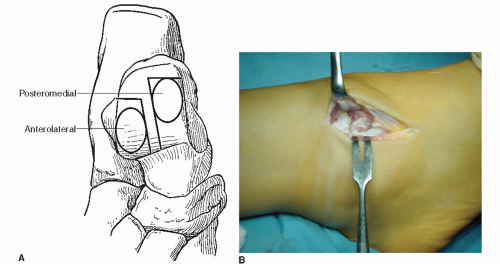

The procedure is done under general or spinal anesthesia. Proper exposure and freedom to move the lower extremity is facilitated by positioning the patient supine on an adjustable bean bag, and a radiolucent OR table that can be tilted from side to side. Whether it is a medial or lateral lesion (Fig. 41.3A), an arthroscopic survey initially confirms the diagnosis and is useful to assess the extent and quality of the articular cartilage in the remainder of the joint. As a first step, an arthroscopic examination is performed to check the intra-articular pathologies and other conditions. Standard anterolateral and anteromedial portals are recommended, but in case of poor visualization, additional portals can be added. Once the decision is made to proceed with mosaicplasty, the surgery can be extended to an open procedure.

Considering that placing the grafts perpendicular to the articular surface is paramount for the success of the operation, and the complex structure of the talocrural joint is difficult to access, a mini-arthrotomy approach is recommended, combined with malleolar osteotomy if necessary. It is possible to access much of the talar dome with a tibial grooving procedure, or with marked plantarflexion of the ankle (Fig. 41.3B).

The grafts are usually harvested from the medial femoral ridge of the ipsilateral knee at the level of the patellofemoral joint; the lateral femoral ridge can serve as an additional harvest site. These areas are the less-weight-bearing surfaces of the knee, and the quality of their hyaline cartilage matches the requirements of the talar surfaces.

Technique: Mosaicplasty for Medial, Lateral, Posterior, and Central OLT

Medial Lesions

Usually a medial malleolar osteotomy is required. Osteotomy at the junction of the medial plafond ensures adequate exposure. When exposure of the medial lesion is sought through an anterior medial-capsular incision, only the anterior portion of the medial talus can be effectively approached. In most cases, a medial OLT is in a central-medial location, ensconced by the medial malleolus, and exposure through a medial malleolar osteotomy is required. If attempting exposure through a medial malleolar osteotomy, perpendicular instrument access to the lesion will be denied unless the line of the cut is sufficiently vertical and then enters the joint at the junction of the medial malleolar and tibial plafond. The more oblique the cut, the more eversion and abduction

of the talus are needed. The lateral capsule and lateral malleolus will be the limiting factors to these excursions and visualizations. The more vertical the cut, the more vertical shear will be placed on the fixation during active ROM through the posterior tibial and Achilles tendons. Fixation of the fragment should be initiated by scoring the line with cautery and predrilling the screw holes to avoid loss of orientation and to ensure precise reduction to the “elective fracture.” Available hardware should include 4.0-mm malleolar screws ranging up to 50 mm long, 2.7- and 3.5-mm cortical screws, and a small, semitubular plate if apical compression is needed.

of the talus are needed. The lateral capsule and lateral malleolus will be the limiting factors to these excursions and visualizations. The more vertical the cut, the more vertical shear will be placed on the fixation during active ROM through the posterior tibial and Achilles tendons. Fixation of the fragment should be initiated by scoring the line with cautery and predrilling the screw holes to avoid loss of orientation and to ensure precise reduction to the “elective fracture.” Available hardware should include 4.0-mm malleolar screws ranging up to 50 mm long, 2.7- and 3.5-mm cortical screws, and a small, semitubular plate if apical compression is needed.

To expose the full breadth of the medial ankle, a curvilinear incision is centered over the medial malleolus (Fig. 41.4A). By blunt dissection and gentle retraction, thick flaps are developed for preserving and protecting the saphenous vein and nerve.

A small anterior incision is made in the anterior capsule at the medial border of the anterior tibial tendon (ATT) to identify the joint line, apex of the medial malleolus, and the lesion (Fig. 41.4B). The posterior tibial tendon (PTT) is palpated immediately behind the malleolus. The overlying flexor retinaculum is incised longitudinally, leaving cuffs for later repair. The PTT is retracted off the capsule to expose the capsule to the lateral lip of the PTT groove. A blunt, small, right-angle or Hohmann retractor is used to protect the PTT and the more posterior lateral flexor digitorum longus tendon, neurovascular bundle, and flexor hallucis longus tendon.

A blunt probe is passed through the joint from anterior to posterior. The exposed ends of the probe and the center of the lesion serve as guides for the line of the osteotomy. The surgeon predrills the screw holes and scores the sides of the intended cut (Fig. 41.5). The osteotomy is completed with a 1-cm, fine-tooth sagittal blade. Performing the osteotomy with care and distraction of the joint can avoid a jagged entry into the joint and scoring of the talus.

A no. 5 suture is passed through the fragment drill holes, the fragment is levered downward, and the capsule is sharply incised anteriorly and posteriorly (Fig. 41.6A). The fragment position and blood supply are maintained by the remaining attached deltoid ligament. At this point, the exposure is still limited. To access the talar dome and expose the lesion, the ankle must be everted and drawn forward and the forefoot abducted in a slow, concerted manner. With patience, the dome will come into proper view (Fig. 41.6B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree