Chapter 6 Authentic Assessment

Simulation-Based Education

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Articulate the case for creating new and different learning experiences in health care education.

2. Distinguish the features of programmable patient simulators and high-fidelity simulation as an educational technique.

3. Explain the forms of immediate feedback (performance-based assessments) that are available with high-fidelity simulation, enumerating at least three approaches.

4. Analyze the term frame of reference as it relates to debriefing techniques following high-fidelity simulation.

5. Summarize reflective assessment techniques that can be incorporated into high-fidelity simulation, listing at least four approaches to assessment.

6. Discuss the benefits of using high-fidelity simulation to standardize student clinical experiences related to rare but critical events and interprofessional team training.

Creating different learning experiences using programmable patient simulators as an educational technique

Simulation is a technique used in health care education to replicate the essential aspects of a clinical situation in an academic setting so that the participant can learn to examine, assess, and manage the event more effectively when it occurs in clinical practice.1,2 Although the use of patient simulators (e.g., role players and standardized patients) has been a long-standing practice in physical therapist education, the use of programmable patient simulators is relatively new. Programmable patient simulators are life-sized mannequins operated by sophisticated computer systems that control a variety of “patient” variables, such as vital signs, breath sounds, heart tones, and vocalizations. When programmable patient simulators are incorporated into a realistic setting (e.g., mock critical care unit with all of the lines, tubes, alarms, and monitors), the simulated environment and experience become realistic, immersive, and uncertain for the participant learning to work with complex patients or manage a clinical event.

Institute of medicine report on health care education competencies

The Institute of Medicine 2003 report,3 Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality, challenges educators across all health care professions to redesign curriculum and restructure clinical learning experiences based on five competency areas: patient-centered care, interdisciplinary teams, evidence-based practice, quality improvement, and informatics. Competencies are defined in the report3 as the “habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values and reflection in daily practice.” Simulation using programmable patient simulators provides an opportunity to address, practice, and assess all five of these competency areas in the context of a realistic patient care setting. Articles in the nursing literature have shown that the use of programmable patient simulators had a positive impact on participant learning and improved performance on subsequent simulation experiences.4–11 Studies with medical students have shown that there was significant improvement in critical assessment skills, performance, and retention of information when training included the use of programmable patient simulators.12–15

Interprofessional education collaborative expert panel report

The 2011 report from the expert panel of the Interprofessional Education Collaborative describes a series of core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice.16 This report envisioned interprofessional collaborative practice as “key to the safe, high quality, accessible, patient-centered care desired by all.” The intent of the report was to define core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice that build on each profession’s disciplinary competencies. Four core competencies (domains) for interprofessional practice were identified16:

Institute for healthcare improvement report to improve patient safety

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement published a set of goals in 2006 designed to improve patient safety.17 These goals set improved communication and teamwork among health care professionals during emergency situations as a priority. The Institute specifically focused on the use of programmable patient simulators as a means to improve communication and teamwork among health care professionals. Teamwork training is of particular importance because patient care has become more complicated and requires a multidisciplinary approach, yet education of health care professionals is still often provided in “silos” within each discipline.18 Studies with Medical and Nursing students demonstrated improved emergency team performance when high-fidelity simulation was incorporated into their training.19,20 There are a number of studies in the nursing and medical literature supporting the efficacy of programmable patient simulation for improving health care education outcomes and multidisciplinary team management of medical emergencies.4,5,12,19,21–23

Features of high-fidelity simulation and programmable patient simulators

Realism, immersion, and integration

Fidelity is a term used to express the degree of realism present in the programmable patient simulator or the simulation. Programmable patient simulators have a variety of observable and clinical features available that add to the degree of realism present in the simulation. High-fidelity simulators have observable features that include the capacity for chest wall movements, pupils that are reactive to light, eyelids that blink, and the ability to converse and vocalize symptoms. Clinical features include breath sounds, heart tones, bowel sounds, and a library of normal and abnormal sounds for each. Simulators can be connected to a patient monitor that displays a variety of parameters in real time, such as electrocardiogram (ECG) data, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation among others. (Figure 6-1).

Figure 6-1 Example of a high-fidelity simulation environment.

(Photo courtesy of Academic Technology and Creative Services, California State University, Sacramento, CA.)

Transformational learning and high-fidelity simulation

The goal of transformational learning is to develop learners with the ability to evaluate, interpret, and perform autonomous thinking, not simply memorize materials or assume the beliefs and judgments of an authority figure. Autonomous thinking is fundamental to professional practice in which each client presents with unique needs and requires creation of a plan of intervention developed in light of best practice guidelines (see Chapter 3 for additional information regarding metacognitive skills and reflective processes that facilitate autonomous thinking and transformational learning). Transformational learning affects the learner’s frame of reference. Internal frames of reference are an adult learner’s acquired “coherent body of experience—associations, concepts, values, feelings, conditioned responses” through which they interpret life experiences.24 These frames of reference, based on knowledge, assumptions, and feeling, determine the actions people will take. The debriefing process is designed to uncover and analyze the participant’s frames of reference that lead to the action taken (see later section, Debriefing Process). The discovery and analysis of a participant’s frame of reference helps learners understand how their frame of reference was used to make a clinical decision as well as learn to scrutinize and transform that frame of reference in order to improve their professional performance on an ongoing basis.

Performance-based assessments with high-fidelity simulation

Preparing the learner for the simulation experience

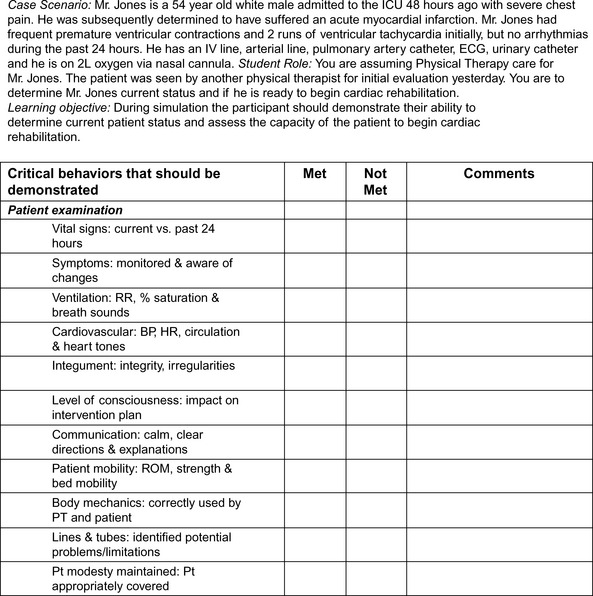

Effective high-fidelity simulation experiences that enable performance-based assessment of the specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes the learner is to achieve begin with development of targeted learning objectives and assignment of presimulation didactic content on which the simulation scenario is based. Ideally, simulation scenarios should be limited to three to four broad objectives, run 15 minutes or less, and include an immediate debriefing process that is equal to or double the time of the scenario.21–25 More extensive objectives and longer simulations can overwhelm participants and lead to less focused debriefing discussions. Each objective can address several “essential or critical behaviors” the participant should perform. For example, Figure 6-2 illustrates a specific but broad objective for the participants. The critical behaviors listed in Figure 6-2 are what the participant is assessed on in the simulation to demonstrate understanding of the objective. Depending on the level of learner (novice, competent, expert), the facilitator may choose whether or not to provide the critical behaviors checklist as part of the simulation preparation. For members of the simulation group who are observing instead of participating at the bedside, the critical behaviors checklist can be an effective tool for helping formulate feedback and reinforcing the content of the objective.

Preparation for the simulation experience may take the form of readings, quizzes, concepts maps, video review of skills, laboratories, or practice on skill task trainers. This enables the participants to enter the simulation learning environment with the prerequisite knowledge and exposure to skills they are expected to synthesize in a patient-centered scenario.26 In addition, participants need to be oriented to the simulator equipment so that lack of familiarity with the functions of the simulator does not affect their ability to perform.27 Preparing students with the simulation objectives, didactic content, and prior practice with skills establishes a baseline for formative learning from which the student can demonstrate an ability to accomplish higher-order activities, such as application and integration of the material during the simulation experience. In addition, simulation enables the facilitator to immediately observe gaps in the ability of a student to apply and integrate knowledge, skill, or convey appropriate attitudes during the simulation, which can then be addressed and clarified in the debriefing session. Subsequent simulation experiences that repeat the scenario or apply the same clinical concepts in a new scenario can form the basis for performance-based assessment using simulation.

Simulation learning environment

The tone the facilitator sets for the simulation experience and subsequent debriefing is pivotal to participant learning. Depending on the size of the learner group, participants may be divided into two groups of “active participants” and “observers.” To enhance realism, the scenario should involve the number of active participants that would most closely mimic what is found in clinical practice, and the roles should be rotated in subsequent simulations.21

Performing in front of peers and a facilitator can be very stressful to participants.21,25,28,29 Therefore, establishing a safe learning environment and a relationship of trust among the facilitator and participants is essential.27,30 This involves understanding the ground rules for respectful communication and confidentiality. Maintaining confidentiality about what happens in the simulation learning experience is an integral part of creating an environment of mutual respect. Addressing any use of video, audio, or written scenario summaries created during the simulation experience is part of this process. In fostering trust, the facilitator should explain how these materials will be stored, who will have access to them, and how and when they will be destroyed. This can be reinforced by having participants and facilitators sign a confidentiality and video/audio agreement, which is used in many simulation learning centers. Creating a psychologically safe and supportive environment where the students feel respected, valued, and free to explore questions, discuss mistakes, and reflect on how to improve practice is essential if the simulation experience and debriefing process are to be successful in creating transformational learning.30,31

In addition to establishing a safe learning environment, the authenticity of the simulation can affect participant performance. Ideally, participants should wear the professional attire they would expect to wear in the clinical situation being simulated. This enhances the fidelity of the scenario and expectation of professional demeanor. Care should be given to simulator moulage and props to create as close to a real-life situation as possible.32 For example, if the participant is involved in working with a patient in the intensive care setting, then the appropriate monitoring equipment, audio alarms, invasive lines and tubes, and safety equipment should be in place (see Figure 6-1). As the “patient’s” condition changes, the participant’s recognition of or failure to respond to alarms and cues in the midst of other patient status changes can be explored in debriefing. Creating an atmosphere that mimics clinical reality allows the participant to suspend disbelief and encourages authentic engagement in the simulated experience to allow for deeper, more comprehensive performance assessment and discovery of the participant’s frames of reference that are driving their clinical decision making.30

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree