Athletic Options for Persons with Amputation

Mark Anderson and Carol Dionne

Learning Objectives

Upon completing the chapter, the reader will:

3. Identify organizations that support athletic participation for persons with disabilities.

4. Compare the different sports and recreation activities available for persons with limb loss.

5. Describe prosthetic components available to active participation in sports of varying types.

The importance of participation in sports, recreation, and/or physical activity for all is well understood. Numerous authors have extolled the virtues of being physically active for both physical and mental health, as well as the prevention of “hypokinetic diseases,” such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. Benefits for individuals who participate in sports or recreational activities include maintenance of normal muscle strength, flexibility, and joint structure and function.2,3 These benefits are essential with the slowing of the functional decline often associated with normal aging or the presence of a disabling condition. Therefore, the goals for increased physical activity for individuals with a disability are to reverse deconditioning secondary to impaired mobility, to optimize physical functioning, and to promote overall well-being.4

In addition to the physical benefits, participation in sports or recreational activities has a significant psychological benefit for both able-bodied and disabled individuals. Both body image and quality-of-life scores have improved in individuals with disability who participate in physical activity and sports.5–7 Participation in regular sport or vigorous recreational activity has favorable effects on the emotional state of adolescents.8 Many psychological constructs, such as improved social acceptance, improved physical self-concept and self-esteem, increased self-efficacy and self-confidence, and a greater locus of control build upon the physical performance accomplishments of the athlete with a disability.9 Even though the benefits of participation in sports and physical activity are well recognized, there is still a disconnect between knowledge and action. This chapter discusses the importance of athletics for persons with disabilities and describes athletic activities and opportunities for active engagement in sports and recreation available to persons with amputation and disabilities associated with loss of limb.

More than half of the adults with disabilities in the United States do not participate in any leisure-time physical activity compared to one-third of adults without disability.10 This reinforces the notion that on average, people with a disability are more inactive than the general population, which leads to the questions, “What are the barriers for those with a disability to their participation in sports or physical activities?” and, “What motivates those with disabilities to participate in sports and recreational activities?” The most common barriers11 to sports participation for individuals with a disability are lack of money, unsuitable local facilities, and health concerns. Additional barriers are lack of local sports facilities, transportation issues, lack of sports offerings for those with a disability, and lack of peer with which to participate. Only 10% of those with a disability report lack of motivation as a barrier to participate. Reasons for participation include health benefits, a feeling of accomplishment after participation, social contacts, and recommendation from a physician or health care professional. In those with limb deficiencies, age, level of amputation, and etiology of amputation do not appear to be related to sports participation following lower-extremity amputation. However, a history of sports participation prior to the amputation increases the likelihood of sports participation following amputation.

Opportunities for sports or recreation participation

Sports for athletes with physical disabilities are governed by various disabled sports organizations and national governing bodies which are disability-specific. In the United States, the disabled sports organizations for athletes with amputation is Disabled Sports, USA (www.dsusa.org/). The motto of Disabled Sports, USA is, “If I can do this, I can do anything!” and its mission is “to provide national leadership and opportunities for individuals with disabilities to develop independence, confidence, and fitness through participation in community sports, recreation, and educational programs.”12 Disabled Sports, USA is comprised of a nationwide network of community-based chapters that offer a variety of sports/recreational programs. In many instances, sports and recreation participation are the final step in the rehabilitation process of individuals following amputation. Sports participation not only improves sports skills, but it allows individuals to experience the emotional highs and lows of winning and losing, which prepares them to face daily challenges and changes following rehabilitation. Disabled Sports, USA, along with other disabled sports organizations, is a member of the United States Paralympic Committee, which sanctions and conducts competitions and training camps to prepare athletes to represent the United States at the Summer and Winter Paralympic Games. The Paralympic Games are the major international multisports event for athletes with physical disabilities, and are second to only the Olympic Games in number of athletes participating. These Games are organized and conducted under the supervision of the International Paralympic Committee and other international sports federations. For athletes with amputation, there are opportunities to compete in 16 different Summer Paralympic sports and five different Winter Paralympic sports.

The U.S. Paralympics Committee also offers an Emerging Sport Program, which is designed to identify, recruit, track, support, and retain Paralympic-eligible athletes with physical disabilities seeking to become internationally competitive. The success of this program depends on the collaboration between community and military programs, partner organizations, military and veteran facilities, and national governing bodies.

Athlete recruitment and identification begins at the local level. Potential athletes are identified in a variety of ways, including military sport camps, site coordinators for specific sports or events, community programs, coaches, technical officials, or current athletes. Once an athlete is identified as having high performance potential, the Emerging Sports manager facilitates appropriate communication between athlete(s) and local program(s), as well as with the appropriate Paralympic sport coaches and high performance directors. Assistance is provided to these athletes by way of connections to local training resources, participation in select emerging and/or national U.S. Paralympics Team camps and competitions, as well as information regarding able-bodied competitions, events and other general sport program opportunities for developing and emerging athletes.

Summer Paralympic Sports

Summer Paralympic sports12 include archery, athletics (track and field), cycling, equestrian, fencing, powerlifting, rowing, sailing, shooting, swimming, table tennis, tennis, sitting volleyball, and wheelchair basketball. In 2016, triathlon and canoe will make their Paralympic debut. Each sport has its own unique set of requirements, which may necessitate a modification of the traditional rules of the sport to allow the disabled athlete to compete.

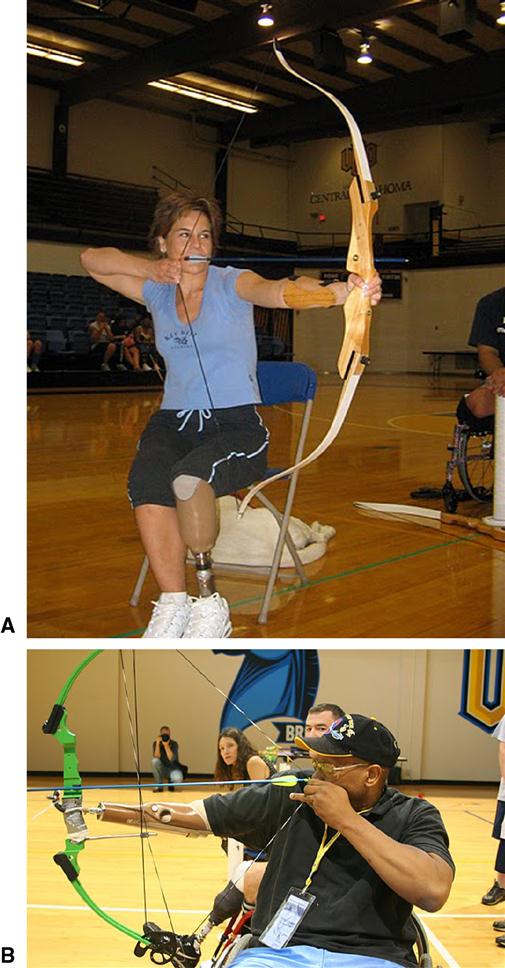

Archery

Archery has been a medal sport since the first Paralympic Games in Rome in 1960. Athletes with physical disabilities demonstrate their shooting precision and accuracy from either a standing or seated (wheelchair) position, in men’s and women’s categories. Paralympic competition format is identical to that of the Olympic Games. Paralympic archers shoot 72 arrows from a distance of 70 m at a target of 122 cm (approximately 48 inches), using a recurve bow (Figure 28-1, A). For competitions other than the Paralympics, athletes shoot at each of four distances. Thirty-six arrows are shot at each distance. The two longest distances use a 122 cm target; the two shorter distances use an 80 cm target (approximately 36 inches). Distances are 90, 70, 50, and 30 m for men; 70, 60, 50, and 30 m for women. Depending upon their classification based upon level and number of amputations and the athletes’ functional ability, athletes competing in other than the Paralympic Games may use either a recurve bow or a compound bow (Figure 28-1, B). Archery competition is open to male and female athletes with upper or lower-extremity amputation/limb loss. Specialized devices are also available to assist athletes with upper-extremity prostheses in drawing back the bow and releasing the string.

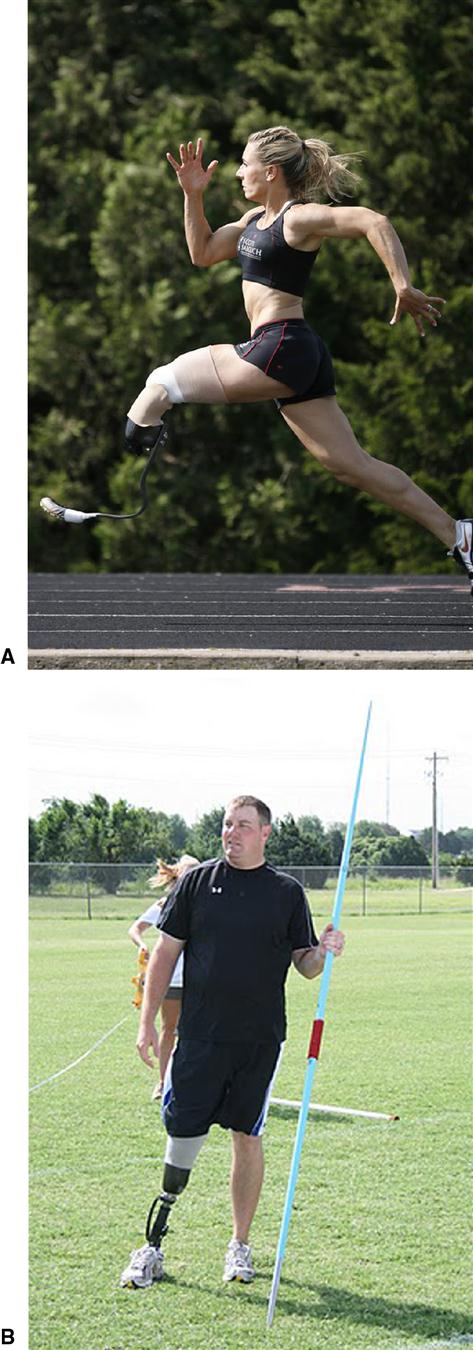

Athletics (Track and Field)

Athletics events are open to athletes in all disability classes and have been a part of the Paralympic program since the first Paralympic Games in Rome, Italy, in 1960. Events include track (Figure 28-2, A) (running distances from 100 m to 10,000 m, plus 4 × 100 m and 4 × 400 m relays), throwing (Figure 28-2, B) (shot put, discus, and javelin), jumping (high jump, long jump, and triple jump), pentathlon (long jump, shot put, 100 m, discus and 400 m) and the marathon. The rules of Paralympic track and field are almost identical to those of its nondisabled counterpart. Paralympic track and field competition is open to male and female athletes with upper- and or lower-extremity single or multiple amputation/limb loss. Prosthetic devices may be used. These have been specifically developed to withstand the demands of sports competition. International Paralympic Committee rules require the use of leg prostheses in track events; however, the use of prostheses in field events is optional.

Cycling

Cycling was first introduced as a Paralympic sport in 1984 in Mandeville, England, and involved only those athletes with cerebral palsy. However, it wasn’t until 1992 that athletes with amputation competed at the Paralympic Games in cycling. At the 2004 Paralympic Games in Athens, handcycling (for wheelchair users) made its debut as a medal event.

Athletes compete in both track (velodrome) and road events. Track events generally consist of sprints as short as 200 m to time trials and pursuits up to 4 km. Relay races consisting of three-person teams are also contested on the track. Competition on the roads consists of time trials and road races. In time trials, athletes start individually in staggered intervals, racing mostly against themselves and the clock. Road races consist of mass starts. Distances vary based on the host country’s discretion. Distances range from 5 km to 65 km in length. Paralympic cycling competition is open to male and female athletes with upper- and/or lower-extremity single or multiple amputation/limb loss (Figure 28-3).

Equestrian

Equestrian made its debut appearance at the Paralympic Games in 1996 with riders from 16 countries competing. By the Paralympic Games in 2008, in Beijing, that number had grown to 73 riders from 28 countries. Riders compete in two dressage events; a championship test of set movements and a freestyle test to music. There is also a team test for three or four riders. Competitors are judged on their display of horsemanship skills demonstrated through their use of commands for walk, trot, and canter. Paralympic equestrian competition is open to male and female athletes with upper- and/or lower-extremity single or multiple amputation/limb loss.

Fencing

Fencing has been part of the Paralympic Games since 1960. Athletes compete in wheelchairs that are fixed to the floor. They rely on ducking, half-turns and leaning to dodge their competitors’ touches. However, fencers can never rise up from the seat of the wheelchair. The first fencer to score five touches is declared the winner. Athletes play the best out of three rounds and compete in single and team formats. Weapon categories for men include foil, epee and sabre. Women compete in foil and epee. Paralympic fencing competition is open to male and female athletes with upper- and/or lower-extremity single or multiple amputation/limb loss.

Powerlifting

Powerlifting is one of the fastest growing Paralympic sports. Paralympic athletes have been competing in powerlifting since 1964; however, it was initially offered only to lifters with spinal cord injuries. Currently, athletes from many different disabled sports groups participate in the sport, assimilating rules similar to those of nondisabled lifters. Athletes compete only in the bench press, and they draw lots to determine order of weigh-in and lifts. After the athletes are categorized within the 10 different weight classes (male and female), they each lift three times (competing in their respective weight class). The heaviest “good lift” (within the weight class) is the lift used for final placing in the competition. Paralympic powerlifting competition is open to male and female athletes with upper- and/or lower-extremity single or multiple amputation/limb loss. There is currently a move to include the single-arm press in powerlifting competitions for those individuals with upper-extremity amputation, with the hope of making this a Paralympic sport.

Rowing

Rowing is a relatively new Paralympic sport, making its first appearance in Beijing in 2008. The sport was selected for Paralympic inclusion in 2005, just 3 years after adaptive rowing made its debut on the world championship level in 2002. The rowing events include the men’s and women’s single sculls, the trunk-arms double sculls and the legs-trunk-arms mixed four with coxswain (Figure 28-4). Paralympic rowing competition is open to male and female athletes with upper- and/or lower-extremity single or multiple amputation/limb loss.

Sailing

Sailing first became a medal sport for the 2000 Paralympic Games in Sydney, Australia. Three boat types raced at the 2008 Paralympic Games in Beijing: the 2.4mR, a single-person keelboat; the SKUD-18, a two-person keelboat; and the Sonar, a three-person keelboat, along with the high performance SKUD-18 m, which must include one female and one person deemed a Functional Classification System “1,” or severely disabled, such as an athlete with quadriplegia. Sailors are seated on the centerline for Paralympic events, but the boat can be sailed with or without either of the seats and configured to suit different sailors’ needs. Because of its design and control, the 2.4mR was selected for single-person races. The boat’s ease of use allows for a level playing field, making tactical knowledge the dominant factor in competition. The Sonar uses a versatile crew-friendly design that is accommodating to athletes with physical disabilities. It is used by sailors of all experience and ability levels, from the novice to international competitors (Figure 28-5). Paralympic sailing competition is open to male and female athletes with upper- and/or lower-extremity single or multiple amputation/limb loss.

Shooting

Shooting, divided into rifle and pistol events, air and .22 caliber, has been a Paralympic sport since 1976. The rules governing Paralympic competition are those used by the International Shooting Committee for the Disabled. These rules take into account the differences that exist between disabilities allowing ambulatory and wheelchair athletes to compete shoulder to shoulder. Shooting matches athletes of the same gender, with similar disabilities, against each other, both individually and in teams. Paralympic shooting competition is open to male and female athletes with upper- and/or lower-extremity single or multiple amputation/limb loss.

Swimming

Swimming for men and women has been a part of the Paralympic program since the first Games in 1960 in Rome, Italy. Races are highly competitive and among the largest and most popular events in the Paralympic Games. Paralympic swimming competitions occur in 50-m pools and, while competing, no prostheses or assistive devices may be worn. Athletes compete in the following events: 50 m, 100 m and 400 m Freestyle; 100 m Backstroke; 100 m Breaststroke; 100 m Butterfly; 200 m Individual Medley; 4 × 100 m Freestyle Relay and 4 × 100 m Medley Relay. Paralympic swimming competition is open to male and female athletes with upper- and/or lower-extremity single or multiple amputation/limb loss.

Table Tennis

Table tennis has been a part of the Paralympic program since the inaugural Games in 1960. Rules governing Paralympic table tennis are the same as those used by the International Table Tennis Federation, although slightly modified for players using wheelchairs. Athletes must use the same quick technique and finesse in the games of competitors from various disability groups, including men’s and women’s competitions, as well as singles, doubles, and team contests. All matches are played best-of-five games to 11 points. Paralympic table tennis competition is open to male and female athletes with upper- and/or lower-extremity single or multiple amputation/limb loss.

Tennis

Wheelchair tennis first appeared at the Paralympic Games in Barcelona in 1992 and is played on a standard tennis court and follows many of the same rules as tennis. However, in wheelchair tennis, a player is allowed to let the ball bounce twice if necessary before hitting a return shot and the doubles court lines are used for both singles and doubles. Also, the athlete’s wheelchair is considered to be a part of the body, so rules applying to the player’s body apply to the chair as well. Paralympic wheelchair tennis competition is open to male and female athletes with upper- and/or lower-extremity single or multiple amputation/limb loss.

Sitting Volleyball

Instituted in 1976 as a standing Paralympic sport, Paralympic volleyball has now become exclusively a sitting sport. Paralympic volleyball follows the same rules as its able-bodied counterpart with a few modifications to accommodate the various disabilities (Figure 28-6). In sitting volleyball, the net is approximately 3.5 feet high, and the court is 10 × 6 m with a 2-m attack line. Players are allowed to block serves, but one “cheek” must be in contact with the floor whenever they make contact with the ball. Paralympic volleyball competition is open to male and female athletes with upper- and/or lower-extremity single or multiple amputation/limb loss.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree