Athlete with Elbow Pain

Michelle Mariani

Ethan Healy

INTRODUCTION

Elbow pain is a common complaint among athletes that can result from acute or chronic conditions. From a diagnostic standpoint, the majority of elbow injuries in athletes occur from chronic processes with an insidious onset; however, some may be acutely exacerbated by a distinct insult. Building a differential diagnosis will depend on the site of the elbow pain and what activities the patient is involved in. A significant proportion of throwing athletes may experience elbow pain, which must be taken seriously and expands the differential significantly. Athletes involved in racquet or stick-based sports are also prone to overuse injuries, while contact and collision sports see the majority of acute elbow injuries.

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY

Osteology of the Elbow

The elbow joint is a hinge (ginglymus) joint formed by the articulation of the distal humerus and the two bones of the forearm, the radius, and the ulna. The trochlea of the humerus, medially, forms an intrinsically stable hinge joint with the trochlear notch of the proximal ulna. The olecranon process proximally and the coronoid process distally form the trochlear notch. Laterally, the radioulnar joint is made up of the articulation of the capitellum of the humerus and the radial head. This joint is important for supination and pronation of the forearm. The elbow has a slight valgus configuration (5 to 7 degrees), referred to as the “carrying angle.”

Ligaments of the Elbow

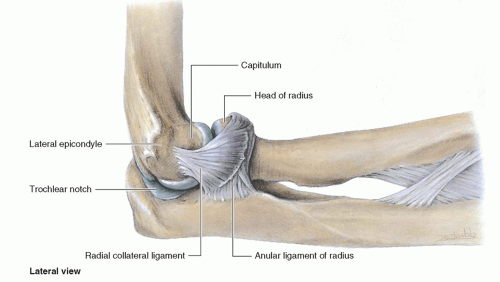

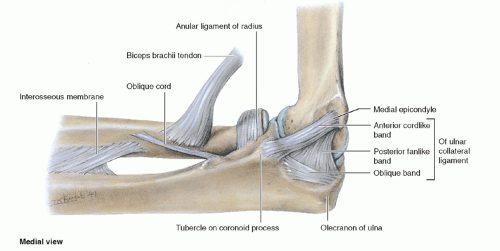

Although the bony structures of the elbow confer an inherently stable joint, the collateral ligaments account for roughly half of the elbow’s varus-valgus stability. The medial (or ulnar) collateral ligament (MCL or UCL) contains a strong anterior bundle and is important in resisting valgus deformation at the elbow (Fig. 13.1). The lateral (or radial) collateral ligament (LCL or RCL) stabilizes against varus force at the elbow and contains the lateral UCL, important for rotational stability of the elbow (Fig. 13.2).

Muscles at the Elbow

The muscles responsible for flexion of the elbow are anterior and include the brachialis, biceps brachii, and brachioradialis. Elbow extension is controlled by the triceps and anconeus, posteriorly. Supination of the forearm is accomplished by the extensor-supinator complex, arising from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. This muscle group includes the extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, extensor carpi ulnaris, and the “mobile wad of three” (extensor carpi radialis longus [ECRL], extensor carpi radialis brevis [ECRB], and brachioradialis). The flexor-pronator mass arising from the medial epicondyle includes the flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor digitorum superficialis, and pronator teres and is important in pronation of the forearm.

Vasculature at the Elbow

The arterial supply to the hand and forearm passes anterior to the elbow. The brachial artery travels anterior to the brachialis muscle and branches into the ulnar and radial arteries in the cubital fossa. The ulnar artery enters the forearm deep to the pronator teres, while the radial artery follows underneath the medial border of the brachioradialis.

Nerves at the Elbow

The radial nerve lies between the brachialis and the brachioradialis along the anterolateral aspect of the elbow. It divides into the posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) and the superficial radial nerve as it crosses the elbow. The PIN dives between the two heads of the supinator, or arcade of Frohse, and the superficial radial branch follows the undersurface of the brachioradialis distally. The median nerve lies anterior to the elbow joint and enters the forearm by diving between the two heads of the pronator teres. The ulnar nerve lies posterior to the elbow joint, along the medial aspect of the humerus, in the cubital tunnel. It enters the anterior compartment of the forearm by passing posterior to the medial epicondyle and through the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris.

FIG. 13.1. Ulnar (medial) collateral ligament. Reprinted with permission from Moore KL, Dalley AF II. Clinical Oriented Anatomy. 4th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. |

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Elbow injuries are becoming more common as more people participate in throwing and racquet sports. The type of injury that is encountered depends, to some extent, on the type of athletic pursuit. The injuries can be roughly grouped into the enthesopathies/tendinopathies (lateral and medial epicondylitis and other rarer similar conditions), valgus stress injuries from repetitive throwing, and peripheral nerve injuries (from repetitive compression or tension). The epidemiology and incidence of specific conditions are detailed under the particular diagnosis in the second half of the chapter.

NARROWING THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

History

The hallmark of an athletic elbow injury is pain at the elbow. The pain frequently radiates distally and is accentuated by palpation over the area of maximal tenderness. Those affected typically may complain of a “cramping” pain in the dorsal forearm over the flexor or extensor muscles. In addition, neurologic symptoms may be present. Weakness may be present in the muscles innervated by the posterior interosseous, including the digital, thumb, and wrist extensors. A throwing athlete with UCL instability will present with a history of medial-sided pain often associated with the late-cocking and acceleration phase of throwing. Pitchers may report a loss of “pop” on the ball. A history of grinding, catching, or locking may indicate the presence of loose bodies, posterolateral impingement, or chondromalacia. Ulnar nerve symptoms have been associated with chronic medial instability.

Evidence-based Physical Examination

Inspection

The elbow should first be inspected for any gross abnormalities or deformities. The entire upper extremity should be exposed to search for any signs of previous trauma, deformity, muscular tone, and skin changes. The carrying angle is the angle made by the upper arm and forearm when the patient stands with palms facing forward. This should be a valgus angle of roughly 11 degrees in men and 13 degrees in women. Overhand pitchers may have a significant increase in this angle as compared to the nondominant arm.1 A decrease in this angle is referred to as cubitus varus or a “gunstock” deformity, while an increase in the angle is called cubitus valgus.

Palpation

The four major bony landmarks should be palpated to look for tenderness, swelling, and crepitus. The medial epicondyle is found along the medial aspect of the distal humerus and is the insertion of the flexor-pronator mass as well as the UCL. The olecranon is a subcutaneous bony process at the posterior aspect of the ulna. Check this structure for any overlying swelling or bogginess that would suggest an inflammation in the overlying bursa. Posterior to the medial epicondyle and lateral to the olecranon, the ulnar nerve can be palpated in its groove known as the cubital tunnel. In addition, palpate the olecranon fossa just proximal to the olecranon as well as the proximal border of the olecranon for osseous irregularities. Along the lateral border of the distal humerus, the lateral epicondyle can be palpated. This is the site of insertion of the extensor-supinators including the “mobile wad of three.” Two to three centimeters distal to the lateral epicondyle, the radial head can be palpated. The examiner can ask the patient to pronate and supinate the forearm to palpate most of its surface.

Range of Motion

The normal range of motion of the elbow is as follows: flexion of 135 degrees or above, extension to at least 0 degree, supination to 90 degrees, and supination to 90 degrees.2 Strength testing should be employed in all planes of motion at the elbow, in addition to at the wrist, hand, and digits to examine for the presence of neurologic deficits or muscular weakness.3

Special Tests

There are several examination maneuvers that are important in diagnosing specific injuries to the elbow joint. These will be explained in order to construct a more thorough examination.

Tinel Test

The ulnar nerve can be assessed at the cubital tunnel. Tapping over the nerve along the groove of the cubital tunnel resulting in distal conduction of pain, paresthesias, or numbness is considered a positive test. A positive test suggests nerve irritation and/or inflammation from compression at the elbow.4

Valgus Stress Test

The valgus stress test is important in assessing the competency of the UCL of the elbow. The elbow must be placed at 15 to 25 degrees of flexion in order to unlock the olecranon from the olecranon fossa. The test is performed by cupping the patient’s elbow with one hand, while holding the distal forearm/wrist with the other hand and applying a valgusproducing force across the elbow. A positive test is confirmed when gapping is detected along the medial aspect of the elbow, as compared to the unaffected side. Medial-sided pain without excessive gapping may be elicited when a UCL sprain is present.2,5

Test for Tennis Elbow

The test for the presence of lateral epicondylitis involves attempting to reproduce the discomfort of this elbow injury. Stabilize the patient’s elbow and proximal forearm while palpating the lateral epicondyle with one hand. With the other hand, resist wrist extension. The test is considered positive when pain is reproduced at the lateral epicondyle approximately 0.5 cm distal, medial, and anterior to the midpoint of the condyle.6,7 Medial epicondylitis can be tested for in a similar way, by palpating the medial epicondyle while resisting wrist flexion/pronation.

Valgus Extension Overload Test

The valgus extension overload test is employed to determine the presence of an olecranon osteophyte impinging on the olecranon fossa. With the elbow in full extension, a valgus-directed

force is imparted across the elbow. Posteromedial pain signifies a positive test. In addition, tenderness or crepitus along the posteromedial olecranon suggests the presence of osteophytes or loose bodies in this area.6

force is imparted across the elbow. Posteromedial pain signifies a positive test. In addition, tenderness or crepitus along the posteromedial olecranon suggests the presence of osteophytes or loose bodies in this area.6

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratory

Routine serology is not required unless an autoimmune etiology is suspected. Lyme titers should be considered for an atraumatic effusion in endemic areas. Fluid analysis including cell count and cultures is often indicated in the setting of a suspected intra-articular infection. Fluid analysis for crystals should be obtained if clinical presentation is suspicious for gout.

Imaging

Plain radiographs are the initial imaging test, particularly in the setting of potential acute fracture and dislocation. X-ray may also show evidence of bony ligament avulsion on the anterior, medial, or lateral sides. The lateral radiograph lends information about the congruency of the joint. Radiographs may show osteophytes or calcific bodies.

Computerized topography (CT) is also very useful in the evaluation of the acute elbow injury. It gives very fine definition of the bony structures of the elbow and can confirm evidence of an effusion. It is also helpful for the evaluation of an occult fracture.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has shown to be useful in many acute elbow injuries. MRI gives outstanding detail and the precise location of ligament and chondral injuries. It is useful in delineating the presence of a discrete macroscopic tear versus the presence of microscopic damage and inflammation, as evidenced by high signal intensity on T2 images. MRI study can be helpful in preoperative planning. MRI examination can be helpful in identifying a space-occupying lesion, can show mass effect on the nerve atrophy and diffuse hyperintensity of the muscles affected on T2 imaging.

MRI arthrography is the test of choice in evaluating for potential UCL injury, articular cartilage injury, or presence of a loose body.

Musculoskeletal ultrasound is growing in popularity due to its high resolution of tendon and ligament structures about the elbow. It can be used in a dynamic fashion to assess for UCL injury. Its high resolution of superficial structures allows for superior imaging of the tendons about the elbow, including the diagnosis of tendinosis and partial tendon tears. Its use is limited by access to trained physicians and sonographers.

Other Testing

Electromyography (EMG) studies may confirm the diagnosis of a peripheral nerve injury about the elbow, although neurodiagnostics early in the course of the disorder are frequently normal.

APPROACH TO THE ATHLETE WITH MEDIAL EPICONDYLITIS (GOLFER’S ELBOW)

Medial epicondylitis, or “golfer’s elbow,” is a tendinosis of the origin of the flexor-pronator mass at the medial epicondyle of the distal humerus. It is the most common cause of medial elbow pain, with an annual incidence of four to seven cases per 1,000 patients.8,9 It is twice as common in men as women, has a typical age range of 35 to 54 years, and has a propensity to occur in throwers, racquet sport athletes, golfers, swimmers, and bowlers.5

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Athletes will typically complain of pain over the proximal, medial forearm, centered at the medial epicondyle. Grip strength may be reduced. Onset is usually insidious. Palpation just distal and anterior to the medial epicondyle will elicit pain. In addition, resisted wrist flexion and pronation will reproduce the patient’s symptoms.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Diagnostic imaging is typically unnecessary. Plane radiographs are usually normal, although traction spurs at the medial epicondyle can be seen on rare occasions. MRI findings include thickening and increased signal intensity of the common flexor tendon and soft tissue edema around the common flexor tendon.10 Musculoskeletal ultrasound is excellent at demonstrating tendon thickening and hypoechoic areas consistent with tendinosis as well as tendon partial tears.

TREATMENT

Nonoperative

Conservative measures are commonly reported to be successful in 85% to 90% of cases

Splinting

Activity modification

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Counterforce bracing

Physical therapy

Corticosteroid injections (care must be taken to avoid the ulnar nerve)11

Ultrasound (not shown to be effective)12

Shock-wave therapy (not shown to be effective)12

Laser therapy (early results are promising)13

Operative

Surgical referral should be considered if conservative management is unsuccessful after 6 months.

Surgical treatment involves removing the diseased portion of tendon, repairing the defect, and securing the tendon to its insertion at the medial epicondyle.

Prognosis/Return to Play

Most athletes with medial epicondylitis will recover with nonoperative methods of treatment.

Complications/Indications for Referral

It is important not to miss a more serious derangement of the elbow such as an UCL injury or an ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow. Ulnar nerve pathology at the elbow can be concomitant with medial epicondylitis.

APPROACH TO THE ATHLETE WITH LATERAL EPICONDYLITIS (TENNIS ELBOW)

Lateral epicondylitis, commonly known as “tennis elbow,” is a tendinosis at or near the origin of the extensor-supinator muscles at the lateral epicondyle. Tennis elbow is the most common cause of lateral elbow pain and typically has an incidence reported to be one to three per 100. The ECRB insertion is usually cited as the culprit and may be damaged by abrasion against the lateral capitellum.16 This damage in the form of microscopic tears to the ECRB results in fibroblastic and vascular proliferation and disordered repair of the tendon.17 Lateral epicondylitis has a high incidence in racquet athletes (up to 50%), equal frequency among men and women, and a typical age range of 35 to 55 years.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree