CHAPTER 16 Assessment of the older person

Introduction

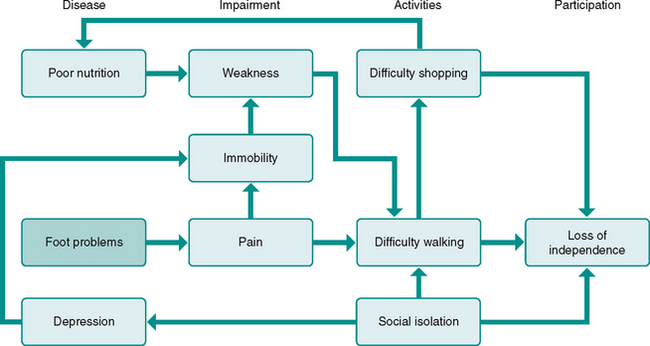

Ageing is associated with significant alterations in the cutaneous, vascular, neurological and musculoskeletal characteristics of the foot and ankle. As a consequence of these age-related changes, foot pain and deformity commonly accompany advancing age. Community-based studies indicate that foot problems are reported by approximately 30% of older people (Barr et al 2005, Dunn et al 2004, Gorter et al 2000) and are associated with reduced walking speed (Benvenuti et al 1995), impaired balance (Menz et al 2005, Menz & Lord 2001a), difficulty performing activities of daily living (Barr et al 2005, Benvenuti et al 1995, Leveille et al 1998) and an increased risk of falls (Menz et al 2006a). Due to the strong association between mobility and independence in older people, the maintenance of foot health can have a significant impact on an older person’s quality of life (Fig. 16.1). Footcare specialists therefore have an important role in the assessment of the lower limb in older people, not only to provide diagnostic clues regarding foot disorders, but also to provide insights into broader issues of physical well-being associated with mobility impairment.

History taking

The initial assessment interview described in Chapter 2 is equally relevant for the assessment of the older person. However, because impairments in vision, hearing and cognition are common in older people, it is essential that the initial assessment interview is conducted in a quiet, well-lit and unhurried clinical environment. History taking in older people may also require the aggregation of information from multiple sources, including family members, friends and carers. This can be challenging, particularly when the information gathered is inconsistent. In some cases it may be necessary to obtain relevant information from each of these sources in isolation in order to develop a more accurate picture of the presenting complaint. This clearly requires striking a balance between patient confidentiality and family involvement (Tinetti 2003).

Use of medications

Due to the age-related increase in prevalence of chronic conditions, the use of prescription and over-the-counter medications increases dramatically with advancing age, with over 80% of people over 65 taking at least one medication, and at least 20% taking five or more (Kaufman et al 2002). Prescribing medications for older people is inherently difficult due to age-related changes in drug absorption, distribution, metabolism and secretion. Furthermore, because most prescription drugs are trialled in younger people, their effects on older people are less predictable, and the likelihood of adverse reactions is not as well understood (McMurdo et al 2005). It is therefore not surprising that a large proportion of hospital admissions in older people are due to adverse drug reactions (Burgess et al 2005, Pirmohamed et al 2004).

Another issue that needs to be considered when documenting medication use in older people is the use of supplements and herbal medications. Use of these medications is highly prevalent among older people, however practitioners often do not document their use, and older patients may not report their use during the medical history interview. A study of 1539 older people found that, although 34% used some form of herbal medication, 70% of these had not informed their physician (Eisenberg et al 1993). This is problematic, as all medications, irrespective of their prescription status, have the potential to interact and contribute to adverse events. Common herbal medications that have been shown to have clinically important interactions with prescription medications include St John’s wort, gingko biloba, echinacea, saw palmetto, garlic and ginseng (Izzo & Ernst 2001, Ernst 2002).

Pain assessment

The effect of ageing on pain is complex. The overall prevalence of pain complaints, with the exception of joint pain, seems to reduce with age (Gagliese & Melzack 1997). While changes in peripheral and central nervous system function that lead to increased pain thresholds in older people may partly explain this reduction (Gibson & Farrell 2004), other factors cannot be excluded, such as the reluctance of older people to report pain. Nevertheless, the degree of functional impairment and level of interference in daily activities associated with pain increases with age (Thomas et al 2004), and because of the key role that the foot has in mobility tasks, foot pain has a considerable impact on health-related quality of life (Chen et al 2003).

As outlined in Chapter 4, numerous multidimensional pain rating scales have been reported and validated in the literature, but they are generally too time-consuming for routine administration in the clinical setting. Visual analogue pain scales provide very limited insights into functional and psychosocial impairments associated with pain, but they are useful indicators of pain intensity, and are easily understood and simple and quick to administer. The use of visual aids, such as lower-limb diagrams or anatomical models, can be useful in determining the location of the pain, particularly if the older person has difficulty describing the location or is physically incapable of pointing to it. Direct questioning regarding pain in other body regions often provides useful diagnostic clues that may not have been otherwise volunteered.

Assessing pain in older people who are incapable of verbal communication is a considerable challenge, and requires observation of physical responses (such as guarding, fidgeting, or restricted movement of the painful body part) and facial expressions (such as frowning, grimacing, or excessive blinking) (Herr et al 2006). Never assume that those who are incapable of reporting pain do not experience it, and all attempts should be made to ensure that physical examination procedures are as pain-free as possible.

Assessment of cognitive status

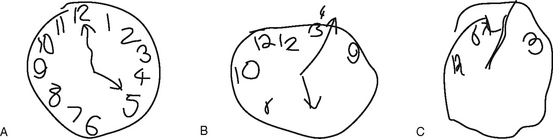

Although the astute practitioner may be able to detect moderate to severe levels of cognitive impairment from general observations and history taking, a structured approach using validated assessment tools will yield more valid findings. The most commonly used clinical screening tool for cognitive evaluation is the Mini-mental State Examination (MMSE), a clinician-administered questionnaire consisting of 30 questions addressing several components of cognitive function (Folstein & McHugh 1975). However, the MMSE it is generally not feasible to implement into routine clinical practice due to its length, and several shorter screening tools have been developed, which are highly correlated with the MMSE. The simplest and most widely used of these tests is the Clock Drawing Test (CDT) (Shulman 2000). Although there are several versions of this test, the most basic approach requires the patient to draw a clock face with all the numbers and hands placed correctly, and to then state the time they have drawn. The following scoring system is then applied:

1. The number 12 appears on top (3 points)

2. There are 12 numbers (1 point)

3. There are two clearly distinguishable hands (1 point)

Scores of <4 are indicative of moderate to severe cognitive impairment (Shua-Haim et al 1996), and warrant further diagnostic evaluation by a geriatrician. Examples of the CDT are shown in Figure 16.2.

Systems examination

The systems examination of the lower limb in older people should be essentially the same as that for younger people, with some particular issues requiring additional consideration. The most fundamental issue in relation to systems examination in the older patient is the tendency for some practitioners to undertake less thorough assessments, due to the incorrect assumption that many aspects of ageing cannot be effectively managed. This is by no means limited to footcare specialists – indeed, ageist assumptions have been demonstrated in most fields of medicine and often result in less detailed diagnostic approaches and the provision of less aggressive treatment approaches (Fraenkel et al 2006). Somewhat paradoxically, systems examination of the lower limb in older people is likely to have a far greater diagnostic yield, and older people may be more likely to benefit from thorough assessments than younger, relatively healthy patients.

Dermatological assessment

Age-related changes

Advancing age is associated with several significant changes to the structure and function of the skin. The thickness of the epidermis does not change appreciably with age, however, the dermal-epidermal junction becomes flattened which may give the impression of atrophy (Gosain & DiPietro 2004). In the foot, there may be an increase in epidermal thickness due to thickening of the stratum corneum associated with plantar calluses (Thomas et al 1985). The shape and size of epidermal keratinocytes becomes more variable, and the rate of production and turnover of keratinocytes may reduce to only 50% of a young person (Smith 1989). Due to this delay in turnover time, the moisture content of keratinocytes is reduced, which, combined with the reduction in sweat gland density, contributes to the dry, scaly appearance of elderly skin (Balin & Pratt 1989). Older people exhibit a significant reduction in the number of capillary loops in the papillary dermis, increased porosity of endothelial cells and a thickened basement membrane, all of which contribute to a less efficient superficial blood supply (Ryan 2004). With advancing age, the rate of growth of the nails also decreases (Orentreich et al 1979), due to both a reduction in the turnover rate of keratinocytes and a reduction in size of the nail matrix itself.

The above changes have several implications for the assessment and treatment of elderly skin. The decreased water content of keratinocytes and decreased density of eccrine glands leads to an overall drying of the skin, which predisposes to hyperkeratosis and fissuring. The reduction in epidermal and dermal immune function increases the risk of infection (Albright & Albright 1994), and the reduced rate of epidermal turnover may increase the time required to successfully treat these infections (Muehleman & Rahimi 1990). Wound healing is also significantly delayed in older people, due to both a reduction in wound contraction and reduced rate of epithelialisation and angiogenesis (Eaglstein 1986). Even if a wound successfully heals, the tensile strength at the wound site is diminished, which increases the likelihood of dehiscence. Subsequently, wounds in older people often require much longer periods of treatment and frequently recur. Bruising is also more likely to occur due to the decreased integrity of superficial blood vessels leading to leakage of red blood cells into the papillary dermis (Muehleman & Rahimi 1990). Due to the reduction in nail growth rate and subsequent thickening of the nail plate, treatment of onychomycosis with either oral or topical agents may take considerably longer in older people, and the possibility of reinfection is much higher (Tosti et al 2005).

Clinical assessment considerations

Dermatological assessment is primarily based on history taking and clinical observations, although as stated in Chapter 8, investigations such as mycology, bacterial and viral culture, histological assessment and patch testing may provide useful diagnostic information. Mycology is particularly important in relation to confirmation of suspected onychomycosis in older people, as dystrophic nails may test positive for a wide range of organisms, and no fungal organisms can be identified in approximately 20% of cases of suspected onychomycosis (Scherer et al 2001). In general, all foot lesions in older people should be investigated for evidence of underlying tissue breakdown and ulceration, and chronic lesions should be carefully documented for potential malignant changes. The ABCD mnemonic (A: asymmetry; B: border irregularity; C: change in colour, and; D: increase in diameter) is a useful general rule for routine assessment of suspect lesions. Practitioners should have a particularly high index of suspicion with regard to non-healing subungual lesions, as this is a relatively common site for the development of malignant melanomas (Lemon & Burns 1998).

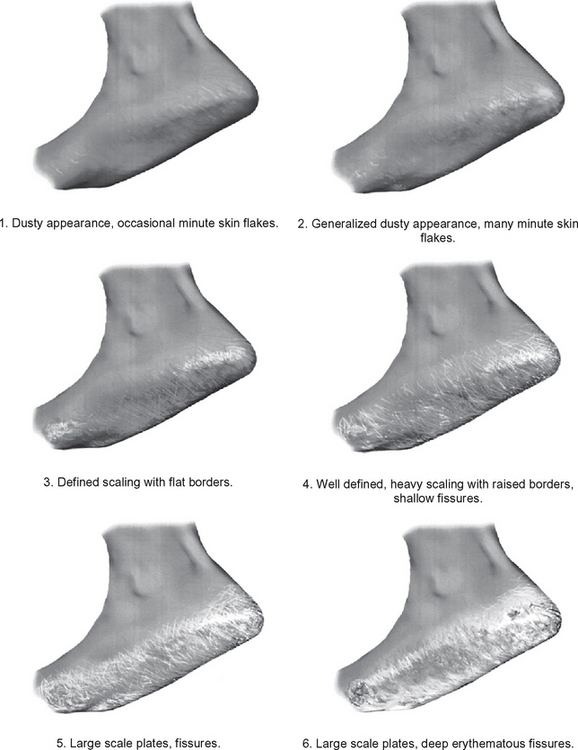

Assessment of skin dryness in the clinical setting can be standardised using the xerosis scale developed by Rogers et al (1989). This scale consists of six images of feet with varying degrees of skin dryness, ranging from a mild, dusty appearance with some small skin flakes, to large scaly plates and deep fissuring (Fig. 16.3). Although the scale has not yet been validated against gold standard measurements of skin hydration (such as electrical capacitance; Lee & Maibach 2002), it has been shown to be a sensitive measurement of skin hydration in response to emollient application (Jennings et al 1998).

Vascular assessment

Age-related changes

Considerable changes take place in the intima of all vessels and the media of large arteries with advancing age. The size and shape of endothelial cells become more irregular, and the overall thickness of the intima and media increases due to collagen cross-linking and invasion of smooth muscle cells (Virmani et al 1991). Elastin fibres in the media of large arteries break down and stiffen, resulting in a reduction in elastic recoil, reduction in overall flow and an elevation in blood pressure (Ferrari et al 2003). At the capillary level, basement membrane thickening and collagen deposition result in a narrowing of the lumen and an overall reduction in blood flow, particularly in the lower limb (Richardson & Schwartz 1985). Relatively little is known about age-related changes in veins, however collagen cross-linking may have a role in the development of perforator vein incompetence (Delis 2004).

The end result of these changes is a generalised reduction in limb blood flow, which partly explains the approximate twofold increase in risk of developing peripheral arterial disease for every 10-year increase in age (Vogt et al 1993). Older people are also more likely to develop conditions associated with venous insufficiency, such as varicose veins and venous ulcers (Carpentier et al 2004).

Clinical assessment considerations

The vascular assessment approaches outlined in Chapter 6 are particularly important in older people, given that age is a major independent risk factor for the development of peripheral arterial disease (PAD). PAD affects approximately 15% of people aged 70 years and over (Selvin & Erlinger 2004), but often goes unrecognised in a large number of patients until the onset of symptoms (Kuller 2001). Given that many older people with asymptomatic PAD have evidence of subclinical cardiovascular disease, the ankle–brachial index has been described as one of the ‘vital signs’ of an older person’s health status (Lawson 2005), and footcare specialists are well placed to detect early signs of vascular disease in asymptomatic older people.

Venous disorders are also common in older people (Carpentier et al 2004), therefore clinical evaluation of venous insufficiency, including observations of telangiectasis, varicosities, oedema and venous ulcers, should be a routine component of geriatric lower-limb assessment. The most serious and potentially life-threatening lower-limb venous disorder, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), should always be suspected in older people presenting with a hot, painful, swollen leg. However, because anticoagulant therapy has potentially serious side effects, it is important that DVT is also accurately ruled out when it is not present. To assist in this process, the clinical prediction rule (Table 16.1) of Wells et al (1995) is particularly useful. This consists of 12 medical history items and clinical observations which can easily be undertaken as part of a routine consultation. The classification of a patient as having a ‘high clinical probability’ of DVT on this scale has been shown to have 91% sensitivity and 100% specificity for the eventual imaging diagnosis of DVT.

Table 16.1 Clinical prediction rule for the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

| CLINICAL FEATURES | |

| Major points | Paralysis, paresis or recent plaster immobilisation of the lower limb Recently bedridden >3 days and/or major surgery within 4 weeks Localised tenderness along the distribution of the deep venous system Calf swelling 3 cm > asymptomatic side (measured 10 cm below tibial tuberosity) Strong family history of DVT (≥2 first-degree relatives with history of DVT) |

| Minor points | |

| CLINICAL PROBABILITY | |

| High | |

| Low | |

| Moderate | All other combinations |

Finally, it has recently been demonstrated that the assessment of foot veins provides a useful insight into the hydration status of an older person (Rosher & Robinson 2004). Given that dehydration is very common in older people (particularly those in institutional care), this simple assessment may help in the early detection of impaired fluid balance. To perform the assessment, the dorsal venous arch vein is occluded by finger pressure and the vein is emptied by stroking proximally. The finger is then released, and the rate and degree of venous return is observed, with a delay of >3 seconds being indicative of potential dehydration.

Neurological assessment

Age-related changes

With advancing age, there is a generalised decline in the size and number of axons, and the myelin sheaths surrounding the axons undergo significant deterioration, leading to a reduction in nerve conduction velocity (Verdu et al 2000). As a result of changes in receptor structure and function, ageing is associated with significant reductions in tactile sensitivity, spatial acuity, and vibration sense, and these changes are particularly pronounced in the lower limb compared with the upper limb. Proprioception (the ability to detect the position of body parts) and kinaesthesia (the ability to detect movement of body parts) rely partly on skin receptors and on Golgi tendon organs and receptors in muscle spindles. As with other mechanoreceptive abilities, ageing is associated with significant decline in proprioception and kinaesthesia in the sagittal plane of the knee (Petrella et al 1997) and the sagittal and frontal plane of the ankle (Gilsing et al 1995, Thelen et al 1998).

Clinical assessment considerations

Lower-limb neurological assessment in older people can be challenging, as it is often difficult to delineate between observations of normal age-related changes and those related to a neuropathic process. The initial assessment interview and history taking may provide useful insights into conditions commonly associated with neuropathy, such as diabetes, chronic alcoholism, vitamin B12 deficiency and the side effects of certain medications. However, self-reported ‘numbness of the feet’ has been shown to be a poor predictor of electrodiagnostically confirmed neuropathy in older people (Franse et al 2000). Furthermore, the use of ankle reflex testing or tuning forks alone to detect neurological problems is confounded by the fact that over a third of people aged over 70 years do not seem to have an ankle reflex (Bowditch et al 1996), and a similar proportion cannot detect vibratory stimuli at the ankle (Prakash & Stern 1973). Therefore, the clinical tests described in Chapter 7 may not provide the same level of diagnostic accuracy when applied to older people.

To address this issue, Richardson (2002) recently developed a clinical screening approach incorporating a range of clinical tests conducted in 100 older people, and correlated their findings with electrodiagnostic tests of peripheral polyneuropathy. The results indicated that all clinical tests differentiated between older people with and without electrodiagnostically confirmed neuropathy. The best prediction of neuropathy was made by using a combination of three tests: the Achilles reflex, vibration sense at the toe, and position sense at the toe. Having two or three abnormal signs demonstrated a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 93% for neuropathy (Table 16.2). Interestingly, the diagnostic accuracy of this protocol was not greatly affected by whether or not the participants had diabetes, indicating that it may have broad application for the detection of neuropathy resulting from a range of conditions.

Table 16.2 Clinical screening approach for the detection of neuropathy in older people

| Test | Description | Cut-off score |

|---|---|---|

| Achilles reflex | Achilles tendon is struck with a reflex hammer | Absent plantarflexion response |

| Vibration sense | 128 Hz tuning fork applied just proximal to the nail bed of the hallux, and time taken until patient reports that the vibration has disappeared is recorded in seconds | <8 s |

| Position sense | Dominant hallux grasped on medial and lateral surfaces by thumb and forefinger. Ten small amplitude up and down movements randomly administered, with patient asked to report direction of movement | <8/10 correct responses |

Musculoskeletal assessment

Age-related changes

There is now extensive literature demonstrating age-related changes in muscle, tendon, ligament and joint structure and function. Due to reductions in the size and number of muscle fibres, older people exhibit between 30% and 60% of the ankle strength of younger people (Doherty 2003), and two recent studies have indicated that older people demonstrate 30% less toe plantarflexor strength than younger people (Endo et al 2002, Menz et al 2006c). Changes in joint tissues may also be responsible for the reduction in range of motion of lower-extremity joints observed in older people. Several studies have shown that ankle dorsiflexion-plantarflexion range of motion reduces with age (James & Parker 1989, Nigg et al 1992, Nitz & Low-Choy 2004), and Nigg et al (1992) have also noted a significant reduction in inversion-eversion and abduction-adduction motion of the ankle joint complex.

More recently, Scott et al (2007) showed that older people had significantly less range of motion at the ankle joint (36° versus 45°, using a weightbearing lunge test), and less passive range of motion of the first metatarsophalangeal joint (56° versus 82°, measured non-weightbearing) than younger controls. Assessment of foot posture also indicated that older people had significantly flatter feet, as indicated by a higher foot posture index and arch index, and a reduction in the height of the navicular tuberosity.

Clinical assessment considerations

Musculoskeletal assessment is clearly of considerable importance in older people, and each of the lower-limb orthopaedic assessments outlined in Chapter 10 are of direct relevance to the assessment of the older foot. However, due to age-related differences in foot structure and function and the higher prevalence of foot deformity, there are several clinical tests of foot deformity, posture, range of motion and strength that are of particular importance when assessing older people.

Foot deformity

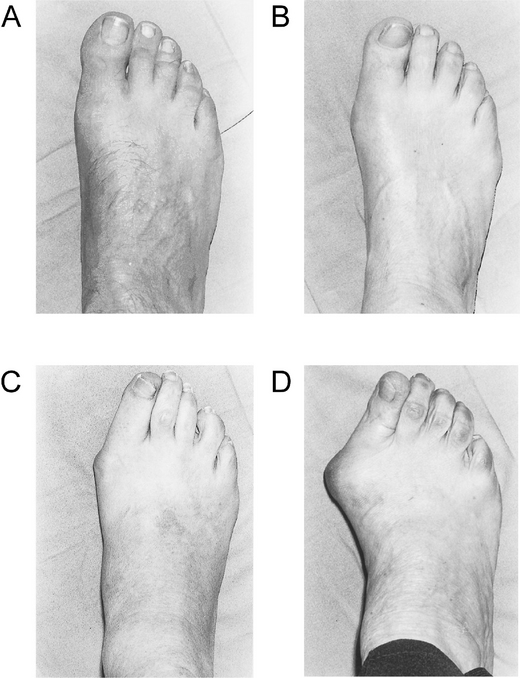

The prevalence of foot deformity increases markedly with age, due to the combined effects of musculoskeletal changes and detrimental effects of footwear. The most common foot deformities in older people – hallux valgus and lesser toe deformities – are often associated with the development of hyperkeratosis and forefoot pain, and have a detrimental impact on balance and functional ability. Hallux valgus can be easily graded in the clinical environment using the Manchester scale (Garrow et al 2001), which consists of four standardised photographs covering the spectrum of the deformity (Fig. 16.4). A study by Menz & Munteanu (2005a) showed that gradings using this scale were significantly associated with hallux abductus and intermetatarsal angles obtained from foot radiographs. Lesser toe deformities (hammer toes, claw toes, mallet toes and retracted toes) can be simply evaluated by assessing the position and range of motion of the metatarsophalangeal, proximal, and distal interphalangeal joints. Thorough assessment of lesser toe function may have some prognostic value, as it has been demonstrated that mobilisation treatment is effective in reducing forefoot pain in people with limited metatarsophalangeal range of motion, but is not effective in people with severely retracted toes (Waldecker 2004).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree