Chapter 2 Assessment

Postural assessment

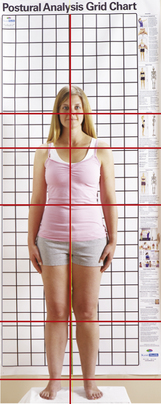

Now the therapist can document head position, shoulder level, hips, knees, and ankles. Take a superficial glance at first, noting things like an asymmetrical stance, contours of the body, and body type. From the anterior view, look for the head position: are the mastoid processes even and balanced? Draw a mental line from acromion process to acromion process: are the shoulders level with each other? Look at the iliac crests and the anterior superior iliac spines: do they appear even? Also look at the head of the fibulas and the malleoli: are they even with each other? If necessary, palpate the structures to confirm your assessment (Figure 2-1).

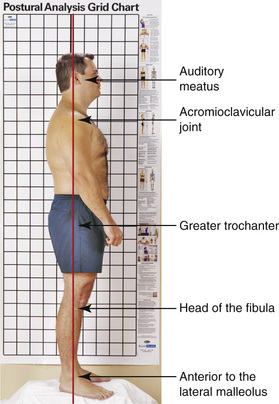

From the lateral view the therapist should look for alignment of the body. Imagine a line perpendicular to the ground, or use a plumb line to assess the posture. This line should go through the external auditory meatus, acromioclavicular joint, greater trochanter, fibular head, and just anterior to the lateral malleolus (Figure 2-2). It is common to see upper crossed syndromes and lower crossed syndromes from this view. Understanding these crossed patterns and applying them throughout the body will help the therapist identify possible areas of weak muscles or hypertonic muscles.

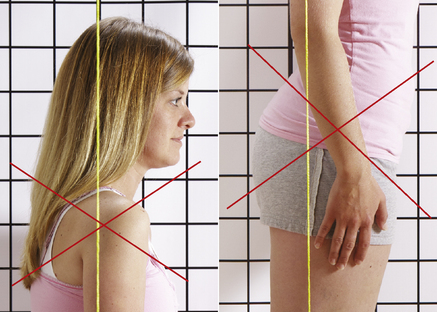

Recognizing upper and lower crossed syndromes can help guide the therapist to an appropriate technique or approach. The upper crossed syndrome presents itself with a protracted shoulder girdle often caused by tightness in the pectorals and the posterior neck muscles. Hypertonicity in these muscles is compensated by weak anterior neck and lower trapezius muscles. The lower crossed syndrome is also prominent from a lateral view. This shows tight hip flexors and low back muscles, and weak abdominals and gluteals. The pelvis appears to tilt forward, often referred to as an anterior tilt (Figure 2-3).

As with the other postural assessments, the therapist should look for symmetry of the contours of the back and alignment of the spine. This can be completed using a plumb line or an imaginary line perpendicular to the ground. Starting from the top down, look for the symmetry of the mastoid processes, acromion processes, inferior angle of the scapula, iliac crest, posterior superior iliac spine, head of the fibula, and the lateral malleoli. This view helps the therapist confirm what he or she noticed from the anterior and lateral assessments. Although in the anterior view a deviation in the hips may look like a hip hike, or elevation, it may not be seen from the posterior. This inaccuracy between assessments may be due to a rotation versus an elevation or depression in the hip. This is important to document so the therapist can follow up with palpation and other functional assessments throughout the session (Figure 2-4, p. 15).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree