POSITIONING

Individual techniques in the application of arthroscopic technology may vary by surgeon, but ultimately, the basics remain the same. For ankle arthroscopy, the patient is typically placed supine, with the knee either straight or bent over a knee stirrup or over the end of the table. The author’s preference is to place the knee straight, unless the noninvasive ankle distractor is used, in which case the knee and hip are flexed. Some surgeons prefer the patient supine, with the knee flexed over the end of the table, the surgeon sitting directly in front of the dependent leg and ankle. For subtalar joint arthroscopy, a lateral recumbent position facilitates access to the sinus tarsi and the posterior ankle and foot. A prone position maybe desirable for situation of more involved posterior joint pathology (

13,

14). These situations may require the use of both the posterior lateral and medial portals.

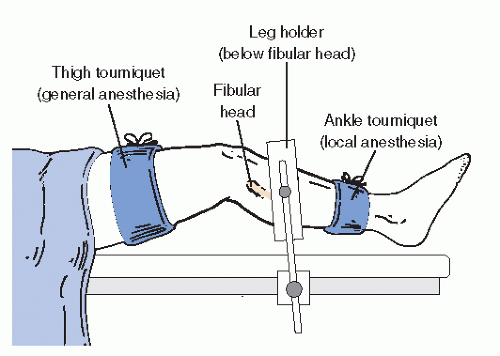

Some authors recommend the use of an arthroscopic leg holder. This accessory device may be helpful in some cases in

which additional leg stabilization or leg elevation off the operating table surface is necessary (

Fig. 53.12). However, in the vast majority of cases, simple padding, straps, and sand bags offer sufficient positioning assistance and immobilization.

HEMOSTASIS

Tourniquet or pharmacologic hemostasis during arthroscopic surgery of the foot and ankle is not mandatory. The pressure of distension is usually adequate to maintain a blood-free field. In those cases in which bleeding is excessive, a small quantity of epinephrine added to the ingress fluid is often sufficient to control small vessel hemorrhage. A tourniquet placed either at the thigh or proximal to the ankle is a safe method for managing bleeding when it is excessive or when epinephrine is either ineffective or contraindicated (

Fig. 53.12). The use of thermoablative wands toward the end of the procedure can facilitate a more rapid cleanup and also help manage bleeding from soft tissues.

At the completion of the operative portion of the procedure, the surgical site is assessed for hemostasis. When there is any question of vascular injury associated with portal development, the tourniquet is released before application of the bandage for inspection and potential ligation of any bleeding vessels. In some situations in which significant intra-articular bleeding is noted, an active, closed suction drain is easily placed through the portal into the joint.

JOINT DISTENSION AND FLUIDS

Once the patient is anesthetized and a sterile field has been created, the ankle joint is distended with fluid. This is usually done before portal development to permit maximal distension of the capsule. The accuracy of portal orientation is enhanced by tactile feel of the needle traversing the proposed path of the arthroscope. Because they are fundamental to joint visualization, distension and maintenance of distension are two of the most important principles of joint arthroscopy. Usually, lactated Ringer or normal saline are used because they are readily available. Questions have been raised as to which fluid is best for performing arthroscopy. Of common fluids available to the surgeon, lactated Ringer is more physiologic than normal saline in all models (

15,

16 and

17). While there are solutions that may be more physiologic to cartilage cells in the laboratory setting, there is no evidence that more expensive solutions are clinically justified.

Distension is maintained by balancing the ingress and egress of fluid from the joint. Gravity drainage or active pumps are used to deliver fluid, usually through the cannula of the arthroscope. When using a small-diameter arthroscopic cannula, distension is often supplemented from a separate ingress cannula. Drainage of fluid from the ankle joint is through cannulas and more commonly along the surface of the instruments inserted in the portal. Maintenance of appropriate distension pressure is sometimes a complex and changing problem, requiring the surgeon’s attention as the case progresses (

18). The surgeon and the assistants should regularly take note of the periarticular soft tissues to observe for potential fluid accumulation in the fascial planes about the ankle. Although there are no reports of significant morbidity from this situation in the ankle, it is usually avoidable and should be corrected, if possible. Compartment syndrome as a result of fluid extravasation is a potential complication in knee arthroscopy but has not yet been reported in ankle arthroscopy.

The distended joint is identified by a visible and palpable “bubble” of distended capsule. In ankle arthroscopy, the ankle joint is often noted to dorsiflex slightly as the end stage of capsular distension draws the foot into dorsiflexion. This phenomenon is a product of the anterior capsular structures drawing the talus up as volume within the joint is accommodated. The volume of fluid that is typically injected when meeting resistance is between 15 and 40 mL, depending on local factors including size and anatomic variation. Introduction of the arthroscopic cannula and associated instruments through the capsule is facilitated by a tautness of the capsule. This tautness can be maximized by reinflating the joint immediately before introducing the cannula, thereby simultaneously maximizing the available volume in the anterior joint pouch and the tension of the joint capsule. A distinct end point in distension will not occur when there is communication of the ankle joint with other periarticular structures. Communication with and extravasation into the tendon sheaths of the peroneus longus and brevis, tibialis posterior, flexor hallucis, peroneus tertius, and the subtalar joint are all possible. The lack of an end point may not necessarily be associated with a communication because a simple rent in the capsule with extravasation into the local soft tissue may also occur.

Intra-articular placement of local anesthetics after completion of the arthroscopic procedure is common practice. Recent publications demonstrate cartilage toxicity (chondrocyte death) with prolonged exposure to lidocaine and bupivicane (

19,

20,

21,

22 and

23). Even adjusting the pH of the local anesthetic has no effect of the toxic effects on cartilage (

21). Ropivacaine has been reported to have less toxicity than bupivacaine in human chondrocytes (

23).

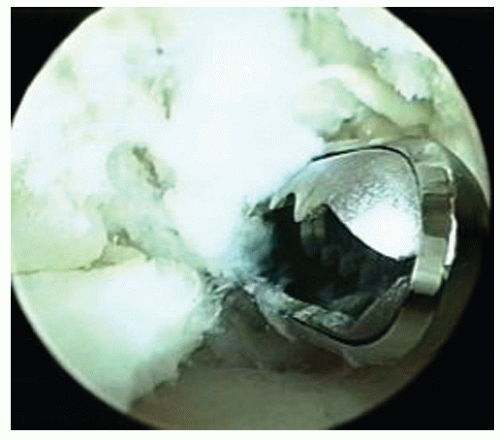

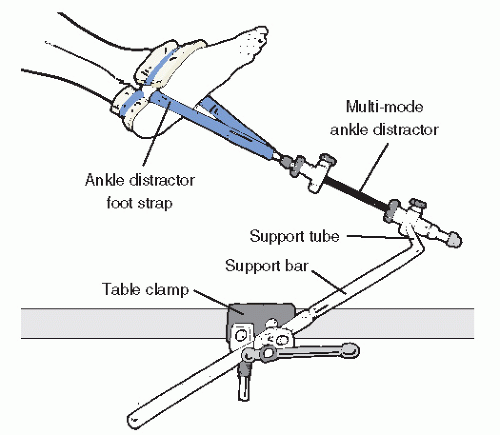

JOINT DISTRACTION

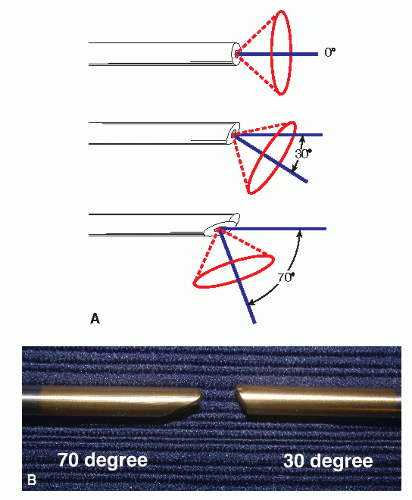

Separating the ankle joint surfaces to allow passage of the arthroscope into it is variably accomplished by a large number of arthroscopic surgeons (

24,

25,

26,

27 and

28). Distraction permits the surgeon to manipulate the arthroscope and its associated instrumentation within the joint without inadvertently damaging or “scuffing” the joint surfaces. The methodology for distracting the

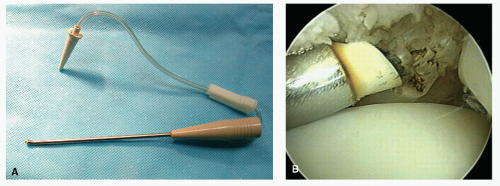

joint is either invasive (employing a device that directly engages bone) or noninvasive (using straps or bands) to pull the articular structures apart physically. Devices vary significantly in complexity, cost, and efficacy. A simple noninvasive distraction involves using bandages affixed to the foot, then applying distal traction either by attaching them to weights or to the surgeon himself, who then leans backward from the ankle (

27,

28). Commercially available noninvasive distraction systems employing mechanical distractors fastened to the operating table, then applied to a padded clove hitch strap binding the hindfoot, are available and have a proven record of safety in the adult patient (

Fig. 53.13). Countertraction for most noninvasive methods is very helpful. A urologic knee stirrup placed in the popliteal fossa is often helpful in providing countertraction. As with scenarios involving positioning a patient, serious care of subcutaneous neurovascular structures are necessary to prevent complications.

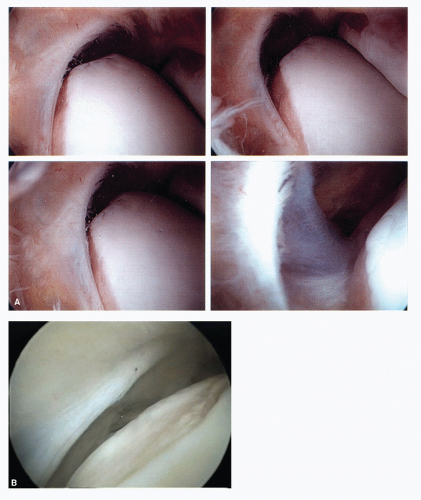

It is quite clear that a well-distended, “loose” ankle joint will allow the experienced arthroscopic surgeon access to the majority of the pathology in the anterior two-thirds of the joint. Laxity of the collateral ligaments, allowing inversion of the talus within the mortise, facilitates entry into the lateral gutter and under the anterior syndesmotic ligament and over the talar dome. Strategic dorsiflexion and plantarflexion manipulation of the talus facilitates excellent visualization of the majority of the talar and tibial surfaces of the joint.

In a minority of patients, a tight joint, especially with limited plantarflexion, requires significant physical distraction to see beyond the dorsal most portion of the talus. Degenerative joint disease with significant osteophytosis of the anterior tibial lip impairs visualization of the dome of the talus. Surgical reduction of the impinging anterior lip is helpful in improving visualization. The combination of reduction of the anterior tibial lip and strategic manipulation allows the majority of cases to occur without the need for application of joint distraction. It is, however, recommended that an ankle joint distractor be available for use in the operative setting for all cases that may need this strategy to meet the goals of surgery. Distraction is routinely used in those situations in which the pathology is in the posterior half of the ankle compartment.

Physical distraction of the subtalar joint is usually not necessary because the capsular reflection of the joint usually provides adequate room for instrumentation. Distraction of the great toe joint and intertarsal joints is usually very helpful for adequate joint visualization. A Chinese finger trap-type noninvasive distractor attached to 5 to 15 pounds of distraction or a invasive minirail distractor that bridges the joint is helpful in maintaining adequate working space.

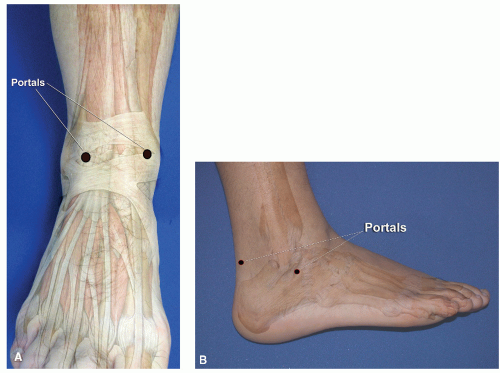

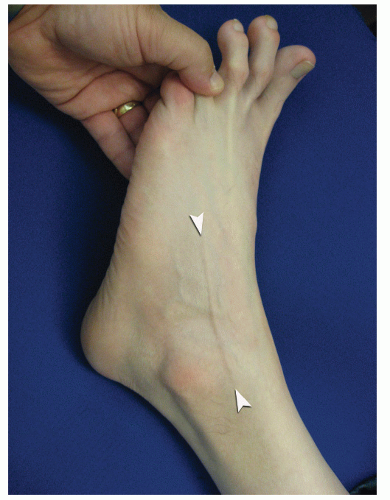

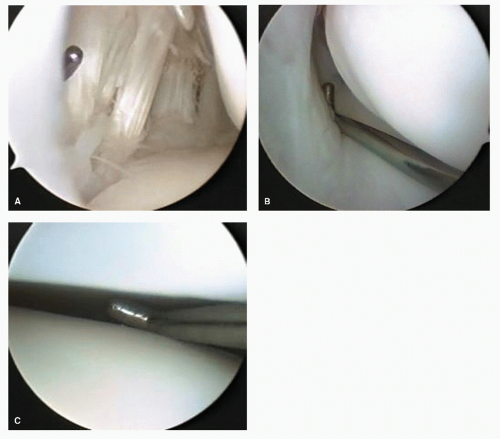

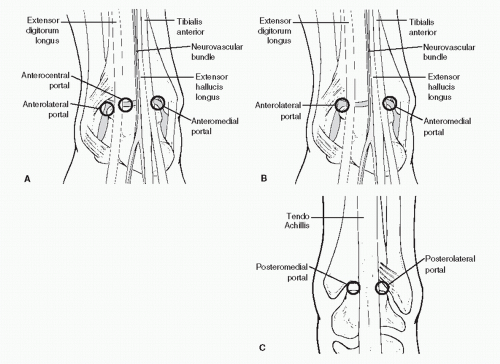

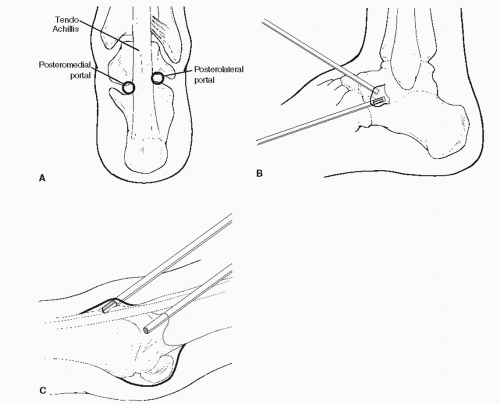

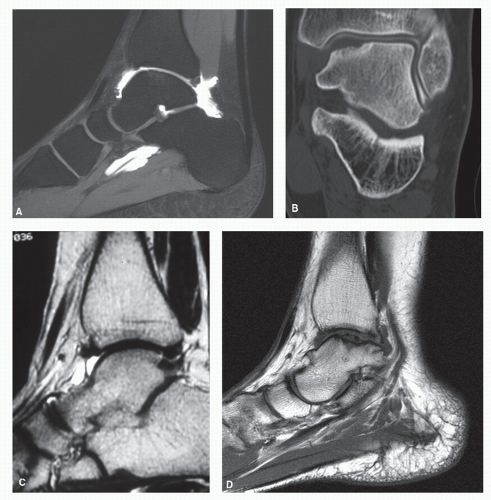

PORTALS

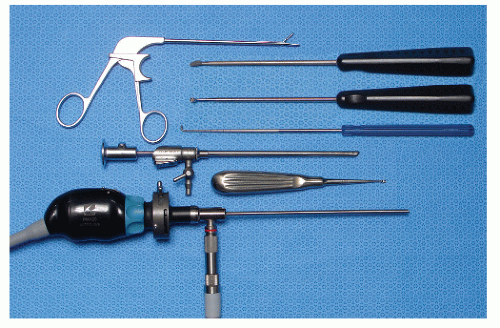

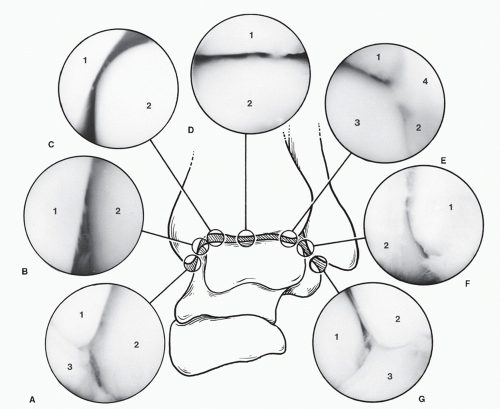

Portals through the soft tissues to the ankle joint are required for passage of the arthroscope and instrumentation. These portals can be safely developed with careful technique and placement. Ideally, once a portal has been developed and the cannula inserted, the cannula can be left in place for safe exchange of instrumentation. With the small instrumentation required for ankle and foot arthroscopy, this procedure is often limited by the lack of availability of instrumentation that fits. Often, instrumentation is carefully inserted into the ankle and other joints of the foot without a cannula. However, overinstrumentation of a portal can lead to creating a large breach of the joint capsule and increase the rate of fluid extravasation into the surrounding soft tissue envelope. Available portals are listed that are commonly in arthroscopic approaches of the foot and ankle (

Table 53.1). It is important for the surgeon to be familiar with topographical anatomy; it is more critical to use sound technique to develop portals since superficial nerve position can be variable and prone to injury (

29). Portal position can be most critical when the scope needs to cross the articular surface deep into the joint. In this situation, the scope must be tangential to the articular surface. It is sometimes wise to use a needle to double-check portal placements, especially in extremities with large amounts of subcutaneous fat deposition and when ankles are being distracted (since this can cause shifting of topographic landmarks) (

Figs. 53.14 and

53.15).

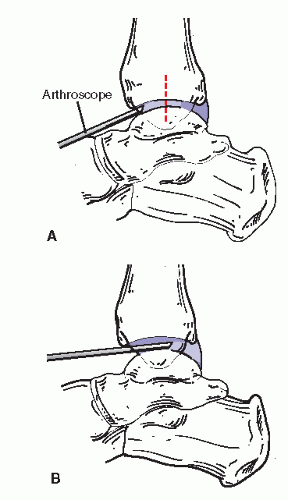

POSTERIOR PORTAL DEVELOPMENT (SWITCHING STICK MANEUVER)

Due to individual variation in the soft tissues surrounding the posterior ankle, it can be difficult to judge the precise location of the joint line and make accurate portal development difficult. A switching stick maneuver can be employed to develop posterior lateral ankle, as well as posterior subtalar portals. The switching stick maneuver in the ankle can be used in a loose or well-distracted joint with instrumentation and scope already present in the anterior compartment, a thin rod or probe with a blunt tip can be directed across the joint from anteromedial to tent the posterolateral capsule. Once an appropriate opening in the skin is made, the rod can be pushed through the soft tissues (

30).

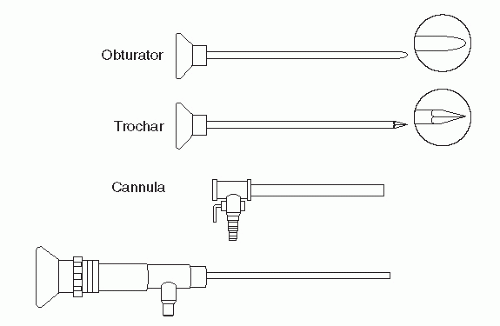

In the subtalar joint, a switching stick maneuver can be very useful in developing the posterior portal. This is accomplished by placing the obturator without the cannula in the anterior portal and advancing it along the lateral gutter through the posterior capsule and terminating adjacent to the Achilles tendon. The skin is tented up and incised to expose the obturator tip. The cannula now can be placed over the obturator and accurately placed within the joint.