Chapter 33 Arthroscopy-Assisted Inside-Out and Outside-In Meniscus Repair

Meniscal tears are an extremely common cause of knee disability. Symptoms can range from persistent low-grade pain to a locked knee. Patients in the former group with mild symptoms may be treated with a regimen of rest, anti-inflammatory medications, and various other modalities, but surgical intervention is common. We are unaware of any published prospective data describing the percentage of patients with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—confirmed meniscus tears that eventually require surgical intervention.25

Surgical treatment options for meniscal tears include excision, repair, and replacement. Partial meniscectomy has been associated with increased risk of osteoarthritis at 10- to 20-year follow-up compared with normal controls in some series.16,21 However, lower rates of osteoarthritis have been noted in patients in whom smaller portions of meniscus were removed.9,20 It is thus desirable to pursue treatment options that preserve or restore functional meniscal tissue. Although it has not been shown that meniscal repair results in the restoration of functional meniscal tissue, some long-term studies have shown less joint space narrowing following meniscal repair than following partial meniscectomy.32 Meniscal repair should be attempted when possible.

Indications

Indications for meniscal repair are constantly evolving. Treatment decisions should take into account tear location and orientation, ligamentous stability, and articular cartilage status. Because only the peripheral 10% to 30% of the meniscus is vascularized, tears in this region have significantly higher healing rates than more central tears.2 In retrospective studies using second-look arthroscopy, Buseck and Noyes11 (98% peripheral and 79% central) and Scott and associates34 (80% peripheral and 73% central) have noted significant differences in healing rates based on tear location. Similarly, Tenuta and coworkers39 noted that all repaired menisci with a peripheral rim greater than 4 mm failed to heal completely in their series.

Tear orientation is also important, because current reconstruction techniques generally only allow for reconstructions of tears with a significant component in the vertical plane parallel to the circumferential meniscal fibers, such as vertical longitudinal tears, bucket handle tears, and certain large flap tears. Radial tears that disrupt circumferential fibers and complex degenerative tears are more difficult to repair and generally heal less reliably.19

Knee stability and concurrent procedures also significantly influence outcomes. Tenuta and Arciero,39 Cannon and Vittori,13 and Barber and Click4 have all demonstrated a better prognosis for repairs performed in conjunction with anterior collateral ligament (ACL) reconstruction. They reported healing rates between 90% and 92% for repairs concomitant with ACL reconstruction and healing rates between 57% and 67% for isolated meniscus repair in stable knees. Similarly, repairs in ACL-deficient knees have been characterized as faring poorly. Steenbrugge and associates38 and Morgan and coworkers27 have found 96% to 100% healing in those with intact or reconstructed ACLs but only 76% to 77% healing in those with ACL deficiency. Open meniscal repairs have demonstrated similar effects of knee stability on healing.14

Techniques for Meniscal Repair

A number of techniques are available for meniscal repair. All generally include preparation of the tear with synovial abrasion, which induces peripheral bleeding in an attempt to promote migration of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells, or meniscal trephination, which attempts to create vascular channels through the induction of holes in the avascular portions of the meniscus. Available arthroscopic repair options include outside-in, inside-out, and all-inside techniques. This chapter will address outside-in and inside-out techniques. All-inside techniques are discussed elsewhere (see Chapter 34).

Inside-Out Technique

Inside-out techniques remain the standard for meniscal repair yielding reproducible, solid fixation of tears in the posterior and middle thirds of the meniscus.12,34,40 The procedure begins with arthroscopic inspection of the joint, identification of meniscal tears, and determination of whether repair is appropriate. If an appropriate tear is identified, an accessory incision is made depending on the location of the tear.

Medial Meniscal Tear

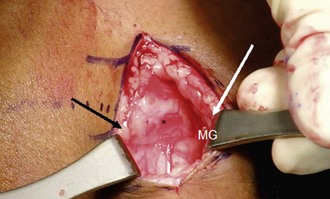

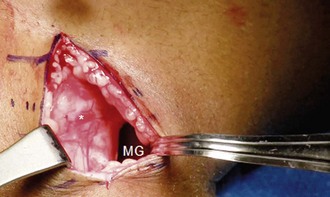

An accessory posteromedial incision is used for repair of medial meniscus tears. A longitudinal incision just posterior to the medial collateral ligament is created and centered, with two thirds of its length below the joint line (Fig. 33-1). The pes anserine fascia is identified and split, retracting the medial hamstring tendons posteriorly (Fig. 33-2). This allows visualization of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle and protects the vulnerable saphenous nerve posteriorly (Fig. 33-3). The medial head of the gastrocnemius is dissected free from the posteromedial joint capsule and retracted posteriorly with a spoon or popliteal retractor (Fig. 33-4).

Figure 33-2 The incision has been taken through skin and subcutaneous fat to the pes anserine fascia (PA).

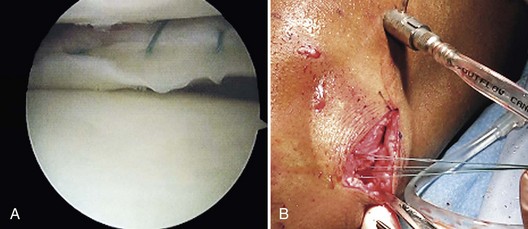

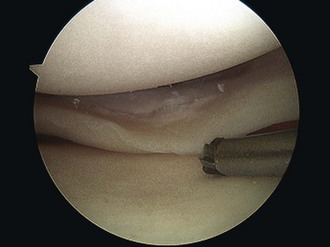

The tear is visualized through the arthroscope and an arthroscopic rasp is used to roughen the edges of the tear (Fig. 33-5). With the arthroscope in the anterolateral portal, a cannula is passed into the anteromedial portal and directed toward the tear for needle passage. Alternatively, the arthroscope can be placed in the anteromedial portal and the anterolateral portal can be used for needle passage. Cannuli of different curvatures are available to facilitate access to any portion of the posterior and middle thirds of the meniscus. A long flexible needle with attached nonabsorbable suture is passed through the cannula, across the meniscus tear, and out through the posteromedial capsule (Fig. 33-6). An assistant ensures capture of the needle by the spoon and guides the needle out of the accessory incision. The procedure is repeated with a second needle attached to the other end of the suture, completing a vertical mattress suture (Fig. 33-7). If more than one suture is required, they are generally placed in an alternating manner on the femoral and tibial surfaces of the meniscus to reduce the meniscus appropriately. After passing all sutures, they are tied in a posterior to anterior direction (Fig. 33-8). It is important to tie the sutures with the knee near full extension because tying them in 90 degrees of flexion could tether the posteromedial capsule and limit knee extension.6

Figure 33-5 An arthroscopic rasp to be used to roughen the edges of the tear prior to repair to facilitate healing.

Lateral Meniscal Tears

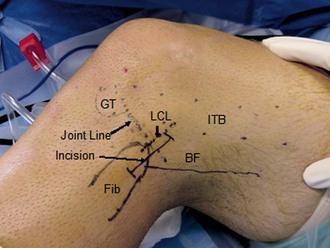

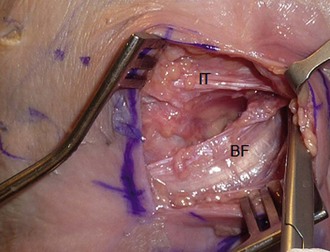

An accessory longitudinal incision is made on the posterolateral knee just posterior to the fibular collateral ligament centered over the joint line (Fig. 33-9). Flexion of the knee helps displace the neurovascular structures further posteriorly to reduce the risk of injury. The interval between the iliotibial band and biceps femoris tendon is developed (Fig. 33-10) until the lateral border of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius is visualized (Fig. 33-11). The lateral gastrocnemius is dissected off the posterolateral capsule and a spoon or popliteal retractor is placed anterior to the tendon, effectively protecting the neurovascular structures located posteriorly and medially (Fig. 33-12).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree