CHAPTER 11 ![]() Arthroscopic treatment of anterior instability—surgical technique

Arthroscopic treatment of anterior instability—surgical technique

Proper patient selection is essential for success with arthroscopic stabilization for anterior glenohumeral instability.

Proper patient selection is essential for success with arthroscopic stabilization for anterior glenohumeral instability.Introduction

Arthroscopic stabilization for anterior glenohumeral instability has become increasingly common, and in many treatment centers, it has become the favored surgical technique. As longer term follow-up studies become available, certain trends dictating the success or failure of arthroscopic stabilization are becoming more evident. Bone defects have become important predictors of clinical failure; thus, recognizing which patients have a critical level of bone loss has become more important.1–6 The recognition of bone loss and other associated pathoanatomic variables will assist clinicians as they decide which patients will benefit from arthroscopic stabilization for anterior glenohumeral instability.2,7 It is also accepted that arthroscopic techniques for anterior shoulder instability must mirror the focus of the open method on retensioning the inferior glenohumeral ligament and restoring the anatomy of the anterior capsulolabral complex. Certain techniques described in this chapter can assist the clinician in accomplishing those goals arthroscopically.8–11 Arthroscopic stabilization for anterior glenohumeral instability has results comparable to the open method in a properly selected patient group. However, failure to acknowledge certain patient factors, perform a thorough preoperative assessment, and execute the procedure properly will adversely affect the result with this technique.2,4–6

With technical improvement, the outcomes of arthroscopic stabilization for anterior instability now rival open procedures.3,9–14 Advantages of arthroscopic management of shoulder instability include lower morbidity, decreased pain, the ability to treat additional pathology, and improved cosmesis. As arthroscopic management of recurrent shoulder instability becomes more commonplace, it is crucial to review what factors influence the success or failure of arthroscopic instability procedures. This chapter focuses on improving the outcomes of arthroscopic stabilization for recurrent anterior instability by examining patient selection, surgical pearls and pitfalls, and adjunctive technical details designed to optimize results.

Indications/contraindications

Indications for arthroscopic management

Arthroscopic stabilization of the patient who experiences a first-time dislocation is a viable treatment option.15–17 The question for this controversial topic becomes, “What is a good result?” Recurrent instability has been the sole outcome measure for many years. However, other considerations such as continued apprehension, failure to return to work or sport, established quality of life outcomes measures, and the development of posttraumatic osteoarthritis are critical in assessing the response to treatment. These factors all play a role in the decision making of the treatment of a patient with a first-time dislocation.

Recurrence rates after an initial traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation have been reported to range from 14% to 100%. The risk of recurrent instability is significantly associated with the patient’s age at the time of initial dislocation. Gumina et al looked at traumatic first-time anterior dislocations in patients older than 60 years of age and found a recurrence rate of 22%.17a

On the other end of the spectrum, Marans studied children with open physes and found a 100% recurrence rate.17b In general, there is a gradient of results, with studies reporting 72% to 95% recurrence in patients younger than 20 years of age, 70% to 82% recurrence between the ages 20 to 30 years of age, and 14% to 22% in patients older than 50 years of age.

Hovelius et al recently reported on the results of a 25-year follow-up study on nonoperatively treated anterior shoulder dislocations.17c They found recurrence in 72% of patients 12 to 22 years of age, 56% of those patients 23 to 29 years of age, and 27% of patients older than 30 years of age. Robinson reported similar results with an 87% redislocation rate in patients younger than 20 years of age and a 30% rate in those over 30 years of age, further emphasizing the importance of patient age on prognosis.17

Sachs et al attempted to clarify which patient population would be most likely to benefit from future surgery after an initial traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation.17d They prospectively followed 131 patients for 5 years and found that the strongest predictor of subsequent instability was age less than 25 years. They noted patients who participated in a contact or collision sport (55%) and patients who used their arm at or above chest level in their occupation (51%) were also at a higher risk for redislocation. However, they found that less than half of these high-risk patients requested surgery and concluded that early surgery, even in these high-risk groups, could not be justified. Interestingly they found that patients who had continued instability but didn’t undergo surgery (“copers”) had significantly lower ASES, Constant, and Western Ontario Stability Index (WOSI) outcome scores than patients with no recurrences or who had surgical stabilization, suggesting a decreased quality of life.

Hovelius recently published a report on the presence of arthropathy 25 years after a primary dislocation.17e Arthropathy was significantly more in patients who experienced recurrent dislocations (40%) versus those patients without a recurrence (18%). Risk factors found to significantly correlate to the development of moderate/severe arthropathy included: age older than 25 years at initial dislocation, high-energy sports activity as etiology of dislocation, recurrence, and alcohol abuse. Buscayet et al had similar findings in their study evaluating arthropathy after anterior shoulder dislocation.17f They had an overall incidence of arthritis of 29% and found risk factors to be older age at the initial dislocation and at surgery, increased number of dislocations, and longer follow-up. They suggested that since the number of instability episodes statistically influenced the development of postoperative arthritis, one might argue for earlier surgery to prevent recurrent instability.

With regard to recent reported results of surgical stabilization for the patient with a first-time dislocation, Bottoni et al prospectively studied arthroscopic stabilization with bioabsorbable tacks versus nonoperative treatment in the active duty military population.15 Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE) and L’Insalata scores were significantly higher in the early surgical intervention group, and the authors concluded that early arthroscopic stabilization with a bioabsorbable tack is more predictable with lower recurrence rates and improved outcomes in young, athletic patients (<25 years). This is consistent with results published on West Point cadets by Wheeler et al and Arciero et al.17g,17h Owens et al recently published a long-term follow-up on their case series of 49 young shoulders (average age 20.3 years) treated with acute arthroscopic Bankart repair using bioabsorbable tacks and found a 14% redislocation rate.17i They reported excellent subjective functional outcome scores with SANE, ASES, and SF-36 scores all averaging greater than 90 and WOSI scores 84% of normal. They concluded that treating young athletes with acute arthroscopic Bankart repair yields durable maintenance of shoulder function and stability and high subjective outcome scores and allows the return to a high level of activity.

In addition to the study by Bottoni,15 there is further level 1 evidence in support of acute arthroscopic stabilization in young patients with a first-time dislocation. Kirkley et al reported on 40 patients younger than 30 years of age who were randomized to immediate arthroscopic transglenoid suture repair or immobilization.16 At 3-year follow-up, they found a 47% recurrence in the nonoperative group versus only 16% in the surgical group. Although they noted a significant difference in WOSI scores at 3 years (16% higher in the surgical group), by 6 years the difference was only 11% and no longer statistically significant. They still felt that it was clinically significant, and recommended early surgical stabilization in young, high level athletes who either participate in risky sports or for whom the timing for surgery is good. A randomized controlled trial by Jakobsen et al of 79 patients (mean age 22), randomized to open Bankart repair or conservative treatment, found at 10 years of follow-up a recurrence of 62% in the conservative group versus only 9% in the repaired group.17j They found 74% of conservatively managed patients had unsatisfactory results using the Oxford score while 72% of surgically repaired patients had good or excellent results. Interestingly, the members of the nonoperative group that required eventual stabilization surgery reported only 63% good or excellent results, further substantiating the argument for initial early surgical care.

To summarize, a recent Cochrane review evaluating the level 1 evidence of nonoperative versus operative treatment of acute first-time shoulder dislocations concluded that early surgical intervention was warranted in young adults (age less than 26 to 30 years) engaged in highly demanding physical activities.17k They reported a 75% reduction of relative risk for subsequent instability in the surgical group in this high-risk patient population.

Patients with traumatic, recurrent anterior shoulder instability are excellent candidates for an arthroscopic instability procedure, but careful patient selection is necessary to achieve optimum results. A thorough history and physical examination should confirm anterior-inferior laxity and adequate bone stock to support an arthroscopic repair. Patients with bone loss less than 20% and glenoid rim fractures that retain a sizable fragment are also suitable candidates.18,19 Throwing athletes with instability pathology also may benefit from an arthroscopic procedure to limit overtightening of capsular tissues and to preserve motion.

Contraindications for arthroscopic management

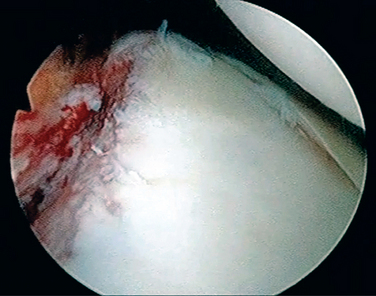

The most important contraindication for arthroscopic management is the presence of significant bone loss. As noted previously, glenoid bone loss of 20% or more will increase failure rates dramatically. The presence of the “inverted pear” also indicates significant bone loss on an arthroscopic view (Fig. 11-1). Significant humeral head bone loss (25% to 30%), “the engaging Hill-Sachs lesion,” also precludes arthroscopic intervention.2,7

Soft tissue injuries associated with anterior dislocation also may rule out arthroscopic repair. Injury to the subscapularis and the humeral insertions of the glenohumeral ligaments and severe capsular damage or deficiency have all been reported with shoulder dislocations.20,21

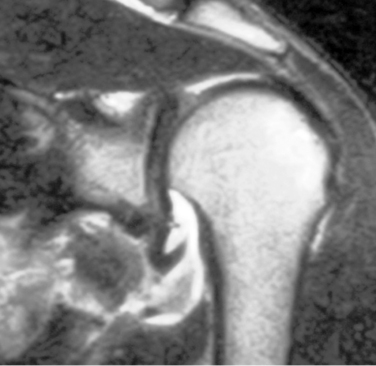

Humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments is a rare but important pathoanatomic variant that can occur in patients with traumatic anterior instability. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast should reveal the pathologic lesion (Fig. 11-2). It is estimated to occur in 2% to 9% of traumatic dislocations. Although some have reported arthroscopic repair of a humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) lesion, most authors recommend open repair of a HAGL lesion. A mini–open approach has been published that avoids violation of the subscapularis tendon. In the majority of cases, a large, extensive, inferior location of the humeral ligament insertion precludes arthroscopic repair.

It should be noted that several investigators have determined that males who are less than 22 years of age, who incurred the initial dislocation when very young, who have had multiple recurrences, and who had a longer time interval from initial injury to surgical intervention have increased failure rates after arthroscopic stabilization.1,4,5 This has been observed even in the absence of significant bone loss. Although this patient profile is not a “contraindication” for arthroscopic treatment, the patient and family should be counseled regarding the increased failure rate in this group.

Controversial indications

Arthroscopic treatment for traumatic anterior shoulder instability in collision athletes remains a controversial topic.1,4,10,22–24 With regard to recurrence, close scrutiny of recent literature suggests that open stabilization still may have a better result than the arthroscopic technique in this population. Boileau et al reported a 75% recurrence rate for male collision athletes, younger than 20 years of age who also had an element of hyperlaxity and bone loss. They described an Instability Severity Score based on age, activity level, presence of laxity, bone loss, and other criteria as a means to determine whether the arthroscopic technique would be successful.4 Burkhart et al reported on a large group of patients that included many rugby players. Those with an “inverted pear or engaging Hill-Sachs defect” had very high rates of recurrence with arthroscopic stabilization. Collision athletes without bone loss did not show a higher recurrence rate when compared with other patients in the study when treated arthroscopically.2 Other reported series do show higher rates of postoperative dislocation for collision athletes when compared with historical outcomes for arthroscopic instability surgery, but some authors have attributed this increased rate of failure to the activity rather than the surgical technique.13,22–25 One study that directly compared open versus arthroscopic techniques did have a higher failure rate for the arthroscopic group. Historical reports of open stabilization procedures for the contact athlete vary in reported failure rates between 3% and 15%. Other research using modern suture anchor techniques has shown dislocation rates that are similar between collision athletes and noncollision athletes. Arthroscopic instability procedures for collision athletes without bone loss should result in failure rates that are similar to the reported failure rates for traditional open instability surgery.

Preoperative history, examination, and imaging

History

Understanding the source and type of instability that the patient is experiencing is critical to the ultimate success or failure of the planned intervention. A thorough history should always include hand dominance, type of instability (dislocation, subluxation), direction of instability (anterior, posterior, multidirectional), requirement for medically assisted reduction versus self-reduction, age at first dislocation, activity level including contact versus noncontact sports, and any treatment that has been rendered to date. In addition, the amount of trauma necessary for the instability episode to occur has obvious implications in management. Those patients whose shoulders “slip out” during sleep or with simple activities such as reaching overhead may require a different surgical plan compared with those who experience instability only with severe trauma. Finally, voluntarism should be assessed since surgical management has a higher likelihood of failing in this patient population with possible psychological overtones to their instability pattern. The patient with recurrent instability is likely to present to the office or clinic.

A standard detailed history is obtained focusing on the following key questions:

The patient’s activity level and expectations are important components of the initial history. The demands the patient will place on any surgical reconstruction must be taken into account when planning operative intervention. In summary, the history should support the diagnosis of traumatic anterior instability and reveal several pitfalls that may complicate arthroscopic stabilization (i.e., bone loss or a wrong diagnosis such as posterior or multidirectional instability) and expose significant hyperlaxity that may require adjunctive treatment.

Examination findings

An initial physical examination should include both observation and motion and strength testing. An examiner may compare the injured and contralateral sides to evaluate muscle atrophy, scapular kinetics, and shoulder resting position. Active and passive range of motion should be evaluated with a thorough examination of pertinent neurovascular and soft tissue structures to include the musculocutaneous and axillary nerves, the rotator cuff musculature, and the deltoid. Strength testing of each component of the rotator cuff with particular attention to the belly-press and lift-off maneuvers for subscapularis integrity should be evaluated. For the belly-press maneuver, the patient is instructed to place the hand facing posterior on the umbilicus. They are instructed to move the elbow forward while maintaining hand contact with the “belly.” If the patient is unable to do this, the wrist will drop into volar flexion and the elbow will not come forward, indicating subscapularis deficiency (see Fig. 2-6 A-C). The lift-off maneuver indicates a complete subscapularis tear. The patient is instructed to place the involved dorsal aspect of the hand onto the sacrum. They are then instructed to “lift-off” the hand from the sacrum (see Fig. 2-6 D-F). Failure to do so indicates subscapularis weakness. Generalized ligamentous laxity must not be missed because it may change the operative approach. A sulcus sign that reproduces pain or instability suggests inferior laxity or redundancy and a clinical presentation of multidirectional instability. Provocative tests must be used to confirm and quantify the degree of instability.

Vital tests includeapprehension testing to spotlight the amount of abduction and external rotation required to reproduce symptomatic feelings of instability. Apprehension in lower degrees of abduction or external rotation suggests bone loss. Apprehension testing should focus on the position that elicits a positive result. A typical patient with recurrent anterior instability would be expected to demonstrate apprehension with the arm in abduction and external rotation (see Fig. 2-8 A). Apprehension in forward flexion and relative adduction suggests posterior instability. A positive relocation test implicates an undiagnosed superior labral tear and/or recurrent subluxation (see Figs. 2-8 B and 2-10). If this force reduces the feeling of instability the test is positive. A load-shift maneuver is used to quantify anteroposterior glenohumeral rotation (see Fig. 2-11 A-C). It is important to note any painful crepitus that results from an anterior or posterior shift. Crepitus with this maneuver suggests a recurrent Bankart lesion or articular cartilage injury. The sulcus/rotator interval should be examined in both internal and external rotation in the adducted arm and must be compared to the contralateral side for appropriate interpretation. A sulcus sign that reproduces pain or instability suggests inferior laxity or redundancy and a clinical presentation of multidirectional instability. The posterior jerk test may be added and if positive, would indicate posterior instability (see Fig. 2-15 A-C). Recent variations of this test have described its use to highlight a posterior labral component of anterior-inferior instability.

Radiographic findings

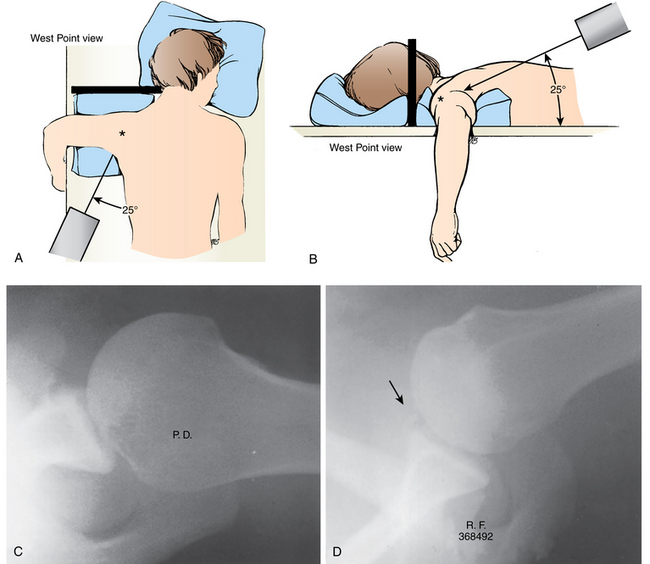

Imaging begins with plain radiography and should include anteroposterior, axillary, West Point, and Stryker views to evaluate glenoid and humeral head bone loss. Significant bone defects of the glenoid and humeral head adversely affect the outcome of arthroscopic stabilization. Plain radiographs can reveal bony defects if the proper views are obtained (Fig. 11-3). The modified axillary radiograph, “West Point” view, is specifically used to assess glenoid bone loss or rim fractures. Itoi has shown high correlation between the West Point view and computed tomography (CT) in estimating glenoid bone deficiency.25a With the patient prone and head turned away from the affected shoulder, the x-ray beam is angled at 25 degrees from the midline and directed through the axilla (Figs. 11-4 and 11-5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree