Arthroscopic Suture Plication for Multidirectional Instability of the Shoulder

Joseph P. Burns MD

Steven J. Snyder MD

History of the Technique

Multidirectional instability (MDI) of the shoulder can be a very difficult problem to effectively diagnose and treat. Patients with complaints of shoulder instability often present with a mixed bag of pathology, having complex histories and variable physical findings. As the understanding of the spectrum of instability has improved, surgical treatment techniques have likewise evolved, becoming more specialized to the various types of pathology that can be present. Early stabilization procedures such as the Putti-Platt, Magnuson-Stack, or Bristow were designed to prevent unidirectional anteroinferior instability, but were poor options for MDI as they did not address the excessive capsular redundancy present in MDI patients, nor could they effectively treat components of posterior instability. These procedures were predicated upon significantly altering normal anterior shoulder anatomy, such as the subscapularis or conjoint tendon, to compensate for dysfunctional capsulolabral structures within the joint. In 1980, Neer and Foster1 popularized the open capsular shift for MDI patients. This procedure effectively reduced capsular volume and proved successful in preventing recurrent instability in anterior, inferior, and posterior directions. While the open capsular shift did not disrupt normal anatomy to the extent of other procedures, it still involved the neurovascular risks of a large surgical dissection, caused considerable scar formation and iatrogenic damage to the shoulder, and required a fairly substantial postoperative recuperation.

In more recent years, the advent of the arthroscope has lead to significant advancements in both the understanding and treatment of MDI. An organized diagnostic examination now allows all relevant anatomy to be fully evaluated in all areas of the shoulder joint. In the past, open procedures did not allow such close inspection of shoulder anatomy and as a result many of the more subtle or posterior pathologic conditions would go unseen and untreated.

In cases of MDI, the arthroscope has also significantly advanced the understanding of shoulder stability and its dependence upon capsular volume. Arthroscopists began noticing that MDI patients had intact structures but increased capsular redundancy. Pathologic instability was often associated with a “drive-through sign” where, owing to excessive ligamentous laxity and redundancy, the arthroscope could be passed across the entirety of the glenohumeral joint without significant resistance. In an effort to spare the normal extra-articular structures and treat only the pathologic anatomy in MDI patients, orthopedists began investigating ways of using the arthroscope to manage the redundant capsule from within the glenohumeral joint.

Early arthroscopic efforts in treating shoulder instability involved transglenoid drilling to stabilize the ligaments to bone.2,3,4 Although effective in reducing capsular redundancy and stabilizing the shoulder, the technique required a posterior dissection for knot-tying, involved risk to both the glenoid and the suprascapular nerve, and was more effective for traumatic, unidirectional anteroinferior instability than for the pancapsular involvement of MDI.

Arthroscopic tack devices have also been used in an effort to keep the stabilization procedure “all inside” and avoid any extra-articular dissection. Created from both permanent and biodegradable materials, these tack devices have had suboptimal long-term results and have been associated with excessive morbidity related to tack breakage, tack migration, articular surface damage, and long-term synovitis.5,6,7,8,9

Several years ago, arthroscopists began using thermal shrinkage as a means to tighten lax shoulder capsules.10,11,12 Although the immediate and short-term reports from the early users seemed promising, the longer-term results have been disappointing and inferior to those of the more traditional

open techniques.13 Anecdotal reports of irreparable capsular necrosis, serious nerve injuries, and articular cartilage damage combined with thermal capsulorrhaphy’s digression from an anatomic reconstruction have made surgeons increasingly wary of the technique.

open techniques.13 Anecdotal reports of irreparable capsular necrosis, serious nerve injuries, and articular cartilage damage combined with thermal capsulorrhaphy’s digression from an anatomic reconstruction have made surgeons increasingly wary of the technique.

At the Southern California Orthopedic Institute (SCOI), an all-inside, all-arthroscopic technique was developed in 1992. Named arthroscopic pancapsular plication (APCP), this technique minimizes morbidity and risk to the patient, allows close evaluation of the entire glenohumeral joint, and enables precise reconstruction of the pathologic anatomy while sparing what is normal. Capsular stitches used in APCP, with or without suture anchors, allow the surgeon to selectively tighten lax ligaments, re-create and widen the labral “bumper,” and complete the operation with minimal morbidity or surgical scarring.

Indications and Contraindications

MDI of the shoulder has been defined as symptomatic shoulder laxity in more than one direction (anterior, posterior, and/or inferior), but it can be a difficult diagnosis to confirm.14,15 Symptoms can vary from subtle painful subluxations to recurrent frank dislocations. Patients with MDI often have symptoms resulting from relatively little or no trauma and usually have normal radiographs. However, a traumatic episode and the presence of a Bankart labral injury or Hill-Sachs fracture do not exclude the potential for MDI as a diagnosis. A thorough history is necessary to establish the activity or position of the upper extremity that reproduces symptoms. An office physical exam as well as an exam under anesthesia are both critical in assessing laxity and planning surgery.

In patients with MDI, some degree of generalized ligamentous laxity is the norm, and it should always be tested and documented. Patients may also have varying degrees of ability to voluntarily sublux or dislocate their shoulders. Physical examination may reveal either obvious or subtle findings such as excessive anterior and posterior glide, a positive sulcus sign, or the ability to voluntarily sublux the shoulder upon request. A positive early warning sign (EWS) is the ability of a patient to easily and willingly dislocate or sublux his or her shoulder, usually with the arm held comfortably at the side. Surgical stabilization of such patients is prone to failure, as these “muscular” subluxators will often stretch out any repair, arthroscopic or open. Other “positional” subluxators are still able to voluntarily sublux their shoulders, but need to bring the arm into a flexed, adducted, and internally rotated position to do so. These patients are more hesitant to sublux their shoulders upon request, as the subluxation is uncomfortable or painful. Positional subluxators are felt to be somewhat better surgical candidates than purely muscular subluxators. A third group, those patients who cannot and will not voluntarily sublux their shoulders at all, makes up the best candidates for surgery. A careful history and office physical exam should differentiate these patient groups.

Once the diagnosis of MDI has been made, many patients will improve with conservative therapy. With a combined program that includes patient education, activity modification, and physical therapy, some patients will avoid surgical intervention. Therapy should be focused on rotator cuff strengthening, periscapular muscular strengthening, maximizing humero–scapulo–thoracic dynamics, and plyometrics. Surgical intervention is indicated when a comprehensive therapy program fails to provide acceptable relief.

Surgical Technique

Anesthesia and Positioning

The patient is given general anesthesia and positioned in the lateral decubitus position. A bean bag is used to maintain proper position and an axillary roll is placed under the dependent thorax to relieve pressure on the dependent shoulder and neurovascular structures. The thorax is allowed to tilt posteriorly 20 degrees, as per standard arthroscopy protocol.

Exam Under Anesthesia

Prior to prepping and draping the positioned patient, examination of the shoulder is performed to thoroughly document the degree and direction of laxity. At our center, this examination is video recorded. Anterior laxity is assessed with the shoulder abducted in a neutral and externally rotated position. Using the weight of the arm to slightly compress the joint, the proximal humerus is gently glided anteriorly and posteriorly, taking note as to whether the humeral head reaches the glenoid edge, goes beyond the edge, or frankly dislocates. Anterior laxity and instability is corrected with anterior capsular plication. Posterior laxity is assessed by positioning the shoulder in a forward flexed, adducted, and internally rotated position. While stabilizing the scapular spine, the examiner gives a gentle posteriorly directed force through the humeral shaft and slowly extends the arm back into an abducted position. With a posterior force applied, a shoulder with posterior laxity will sublux in the adducted position, and the examiner will feel a reduction as the arm is moved into the abducted position. Posterior laxity and instability are corrected with posterior capsular plication and closure of the posterior portal. Inferior laxity is evaluated by the subacromial sulcus test. With the arm at the side, the examiner exerts a downward pull on the arm in both neutral and external rotation. With a competent rotator interval, the amount of displacement inferiorly should decrease with the arm in an externally rotated position. If the rotator interval is incompetent, the inferior displacement of the humerus is similar in both positions. Inferior laxity and instability is corrected by plicating the rotator interval.

The information gained under anesthesia must be compared to that obtained during the office physical exam and to the exam of the contralateral arm. Laxity, a function of the soft tissues, and instability, a subjective feeling of the joint disassociating, are not synonomous and should be evaluated independently. The examiner must use all information available to determine which areas of the joint need surgical plication and which do not. In true MDI, a patient will be lax and unstable in multiple directions and the following pancapsular plication will be carried out.

Procedure

After surgical skin preparation, the arm is placed in a padded traction sleeve with approximately 10 lb of one point inline traction holding it in standard 70 degrees of abduction and 10 degrees forward flexion. Weight can be altered for larger or smaller limbs. The pertinent acromial and clavicular borders are marked on the skin with a sterile marker. The glenohumeral joint is entered using a standard posterior portal created approximately 2 cm inferior and 1 cm medial to the posterolateral acromial angle.

Once the arthroscope is inside the joint and the joint is distended with fluid, an anterosuperior portal (ASP) is created using an outside-in technique. A spinal needle is used to ensure proper placement prior to making a skin incision. Ideal portal placement is 1 cm anterior to the anterolateral acromial angle, angled toward the axilla within Langer lines, entering the joint in the superior aspect of the rotator interval, just anterior and superior to the biceps tendon. This position anticipates the placement of a second portal, the anterior midglenoid portal (AMGP), which will be placed later in the procedure. Of note, the rotator interval tissue is often very robust tissue and difficult to penetrate with a working cannula. It often needs to be dilated with a smaller obturator prior to placement of the cannula. At SCOI, a 5.75 mm clear cannula is used in the ASP (Crystal Cannula, Arthrex, Inc, Naples, Fla).

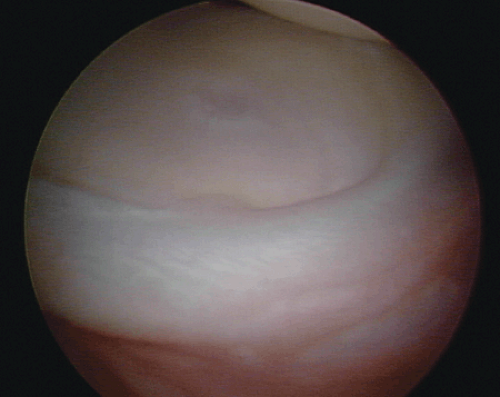

Once the posterior and anterosuperior portals are established, a comprehensive 15-point arthroscopic glenohumeral examination is performed.16 A bursal arthroscopic examination can be performed when indicated. While examining the glenohumeral joint, special attention should be paid to several areas. The amount of overall volume is noted. A patulous posterior capsule will often allow a very broad view of the posterior joint, termed a “skybox view” (Fig. 4-1). The status of the biceps anchor and anteroinferior labrum will always be noted, but the humeral attachment of the glenohumeral ligaments, both anteriorly and posteriorly, must be inspected as well. When ruptured anteriorly, this is termed a humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments (HAGL) lesion and is best viewed with the arthroscope in the anterior superior portal, anterior to the humeral head, with the lens looking up laterally at the humeral capsular insertion. When the ligaments are ruptured posteriorly, it is termed a reverse HAGL (RHAGL). A RHAGL is best identified with the arthroscope in the anterior superior portal, posterior to the humeral head, with the lens looking up lateral at the humeral capsular insertion. It is important to rule out such capsular tears prior to performing an arthroscopic pancapsular plication (Fig. 4-2).

Fig. 4-1. The “skybox view” of the posterior glenohumeral joint in a patient with excessive capsular volume.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|