Arthroscopic Suprascapular Nerve Release

Alan F. Barber

James A. Bynum

Suprascapular nerve disorders are an often overlooked source of shoulder pain and dysfunction and are estimated to comprise 1% to 2% of all shoulder complaints (1). Since Thompson and Kopell (2) first described this condition in 1959, many authors have sought to characterize the diagnosis and treatment of suprascapular nerve entrapment. Based upon a greater appreciation of this pathology, effective treatments have been described, providing symptomatic relief and the return of function.

ANATOMY

The suprascapular nerve is a peripheral sensory motor nerve arising from the upper brachial plexus that receives contributions from the fifth, sixth, and, occasionally, fourth cervical nerve roots (3). It provides motor innervation to the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles as well as sensory innervation around the shoulder (4). From its origin in the superior trunk of the brachial plexus, the nerve passes through the posterior cervical triangle and arises deep to the trapezius and omohyoid muscles where it then follows the suprascapular artery to enter the suprascapular notch. While the artery passes over the transverse scapular ligament (TSL), the nerve passes beneath it before entering the supraspinatus fossa (Fig. 27.1). A superior articular branch arises from the main trunk of the nerve at or near the ligament and travels with the main nerve through the notch. This branch supplies sensory innervation to the coracoclavicular and coracohumeral ligaments, the acromioclavicular joint, and the subacromial bursa. Within 1 cm of passing through the notch, two motor branches arise, which terminate in the supraspinatus muscle. The main nerve then courses inferiorly through the spinoglenoid notch, giving rise to yet another small sensory branch that innervates the posterior glenohumeral joint capsule. The remaining nerve enters the infraspinatus fossa, terminating as multiple motor branches to the infraspinatus muscle (4).

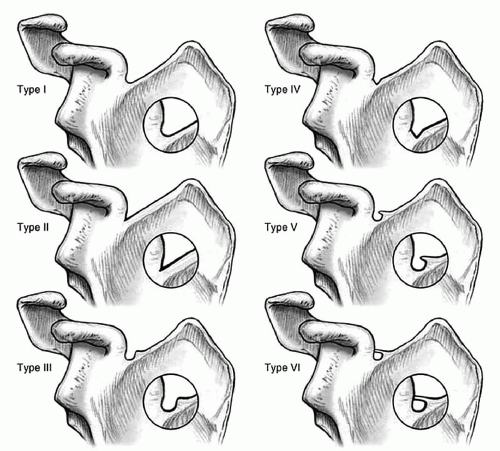

There are two locations of suprascapular nerve entrapment (the suprascapular notch and the spinoglenoid notch). Six types of supra scapula notches have been described (5). The most common types are a wide, a shallow “v”- (type II, 31%), and a “u”-shaped notch (type III, 48%) (Fig. 27.2). Although it has been suggested that entrapment may be associated with a calcified, bifid, trifid, or hypertrophied TSL, no studies have linked nerve entrapment to scapular notch morphology.

In contrast, the spinoglenoid notch is a fibro-osseous tunnel composed of the spinoglenoid ligament and the spine of the scapula. Cadaveric studies have placed the actual occurrence of a spinoglenoid ligament to range from 3% to 80%, but Plancher et al. (6) attributed this variation to be due to errors in specimen preparation and reported the spinoglenoid ligament to be a distinct anatomic structure present in 100% of specimens. This ligament originates from the lateral aspect of the scapular spine and the deep fibers insert distally into the posterior aspect of the glenoid neck, whereas the superficial fibers insert into the posterior glenohumeral joint capsule (Fig. 27.1).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The suprascapular nerve, like all peripheral nerves, is susceptible to injury from compression or stretching, resulting in nerve ischemia, edema, and decreased conduction. Previous animal studies have shown that as little as 6% increase in length causes conduction abnormalities, and 15% or more may cause irreversible damage.

Normal shoulder girdle motion does not result in a translational motion of the suprascapular nerve through the suprascapular notch and thus frictional injury does not appear to contribute to nerve damage (5). However, the nerve pass through a sharp turn around the TSL while passing through the notch, making it susceptible to compression against the sharp, inferior margin of the ligament. The term “sling effect” describes this potential source of nerve injury (5), which can be exacerbated by shoulder depression, retraction, or hyperabduction. This mechanism is often associated with overuse or athletic injuries and is thought to be the most common cause of suprascapular nerve impingement at the suprascapular notch.

Direct traumatic injury to the nerve is not common due to its relatively protected position underneath the trapezius muscle. Injury from scapular or clavicle fracture, shoulder dislocation, or penetrating trauma has been reported. Iatrogenic injury from procedures such as distal clavicle excision greater than 1.5 cm has also been reported. A cadaveric study by Warner et al. (7) suggested that a nerve traction injury may occur in massive rotator cuff repairs when the supraspinatus or infraspinatus tendons are mobilized more than 3 cm, but no clinical studies have demonstrated nerve damage from this mechanism.

Distal suprascapular nerve injury at the spinoglenoid notch is often the result of direct compression from a mass, most commonly a ganglion cyst (Fig. 27.5A, B), or from repetitive overhead or throwing activity. Injury at this level spares the supraspinatus muscle, but affects conduction to the infraspinatus. Ganglion cysts near the spinoglenoid notch result from synovial fluid extravasating into the tissues through a posterior capsulolabral tear, creating a one-way valve effect. At this location, the sensory fibers have already branched and the nerve is mainly a motor nerve. Consequently, posterior shoulder pain often associated with these lesions may be a result of the posterior labral tear itself. Other reported but rare causes of compression include synovial sarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, renal cell carcinoma, and schwannoma.

In addition to compression, nerve injury at this level can occur secondary to repetitive overuse such as that seen with overhead-throwing athletes. Plancher et al. (8) conducted a cadaveric study involving pressure measurements in the spinoglenoid notch, as the shoulder was taken through the six phases of the throwing motion. The spinoglenoid ligament insertion on the posterior capsule made the ligament susceptible to the same dynamic forces that act on the posterior capsule itself during the throwing motion. The pressure measurements within the spinoglenoid notch increased during every phase of the throwing cycle, peaking at the follow-through phase with shoulder adduction and internal rotation (8). This explains why atrophy and electromyographic changes in the infraspinatus muscle are often observed in pitchers and in the dominant arm of competitive volleyball players. A subsequent release of the spinoglenoid ligament resulted in relief of the high pressure readings throughout the entire throwing cycle (8). Another theory of distal nerve injury in overhead athletes involves repetitive microtrauma to the intimal lining of the suprascapular artery, ultimately leading to microemboli to the vaso vasorum of the suprascapular nerve and nerve injury (9). However, the clinical data to support this is currently insufficient.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

History

Patients with suprascapular nerve entrapment are typically between 20 and 50 years of age and commonly have deep, aching posterior and lateral shoulder pain in their dominant arm. While occasionally associated with trauma, the usual onset is insidious and often exacerbated by overhead activity. Weakness in external rotation or abduction may be reported. Isolated infraspinatus weakness without significant pain is not uncommon with distal spinoglenoid notch lesions since most sensory fibers branch more proximally. Alternate diagnoses to consider include cervical radiculopathy, brachioplexopathies, rotator cuff pathology, and other glenohumeral joint pathology.

Physical Exam

Proximal lesions at the suprascapular notch result in atrophy of both the supraspinatus and the infraspinatus muscles. Tenderness at the notch, located posterior to the clavicle in the trapezius muscle belly overlying the scapular spine can often be elicited. Weakness in external rotation and abduction compared with the uninvolved side is not uncommon. Distal suprascapular nerve compression at the spinoglenoid notch results in isolated atrophy of the infraspinatus muscle (Fig. 27.4). Posterior shoulder tenderness overlying the spinoglenoid notch and isolated weakness in external rotation may be present.