Arthroscopic Subtalar Arthrodesis

Phinit Phisitkul

Tanawat Vaseenon

Subtalar arthrodesis has been successfully used for the treatment of subtalar arthritis, subtalar instability, tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction, and talocalcaneal coalition. Advances in foot and ankle arthroscopy and instruments allowed the arthroscopic arthrodesis of the posterior subtalar joint to be technically feasible in select cases. Tasto (1) described the technique with the patient in a lateral position using a combination of portals placed laterally. Amendola et al. (2) described posterior arthroscopic subtalar arthrodesis (PASTA) using the posterior hindfoot endoscopy portals, with the patient in a prone position. The efficacy and safety of the technique was supported by anatomical studies and a number of case series. The advantages of this technique include minimal pain, less scarring, fewer wound complications, high fusion rate, and that it is performed as outpatient surgery. With proper patient selection and familiarity with the technique, the arthroscopic subtalar arthrodesis may be found to be a useful addition to the surgeon’s armamentarium.

CLINICAL EVALUATION OF SUBTALAR PAIN

History and Physical Examination

Patients with subtalar joint problems usually present with activity-related pain and swelling in the hindfoot aggravated by walking on uneven grounds. Common pathologies of the subtalar joint include primary arthritis, inflammatory arthritis, posttraumatic arthritis, and talocalcaneal (T-C) coalition. History of underlying systemic arthropathy or previous injuries should be obtained. Patients with T-C coalition have the onset of pain in the second decade but some presents in their 30s, often after an injury.

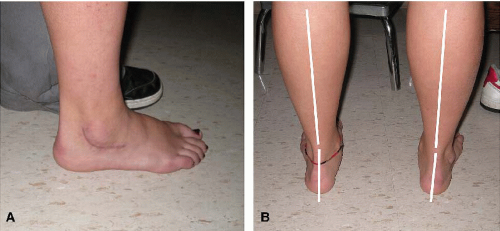

Physical examination should include screening for the involvement of the hips, the knees, and the back. Thorough examination of the foot and ankle is the cornerstone of the clinical evaluation. Gait and limb alignment should be observed with the patient both standing and walking (Fig. 94.1A, B). Swelling of the subtalar joint is located around the subfibular area. Disappearance of the subfibular concavity is sometimes observed. Any surgical scar seen should be documented. Patients with T-C coalition involving the middle facet may have a bony prominence in the posteromedial ankle (Fig. 94.2). This structure may compress the tibial nerve simulating symptoms and signs of a tarsal tunnel syndrome in up to one-third of the cases. Tenderness on palpation of the subtalar joint is the most useful test in the evaluation of subtalar problems. Maximum tenderness is usually triggered by palpation along the subtalar joint laterally just distal to the tip of the fibula. Attention should be paid to rule out pain from the peroneal tendons, which are located superficial to the subtalar joint. Direct palpation over the peroneal tendons while the patient holds the foot in dorsiflexion and eversion can help differentiate the source of tenderness. The sinus tarsi area is sensitive to direct pressure, therefore a comparative evaluation of the contralateral side is recommended. Crepitus can be felt at the joint line while the foot is passively everted and inverted. Patient with a T-C coalition may have tenderness on palpation over the middle facet just dorsal to the sustentaculum tali. Range of motion of the subtalar joint is evaluated with the knee in 90° of flexion in prone or sitting position. In patients with a T-C coalition, the range of subtalar motion can be deceptively normal due to the compensatory motion through the transverse tarsal joint. Peroneal spastic flatfoot, if present, is suggestive of the presence of T-C coalition. The peroneal muscle spasms can be demonstrated by passive forced plantarflexion or inversion. Flexibility of the coronal plane malalignment, varus or valgus, can be evaluated using Coleman’s blocks. When the alignment is improved with the blocks, medial or lateral forefoot postings can be applicable as a mean of nonoperative treatment.

Imaging

Radiographic evaluation is essential for the evaluation of subtalar joint. We recommend weight-bearing, orthogonal views of the foot and ankle, oblique views of the foot, and a hindfoot alignment view. Ankle joint should be carefully

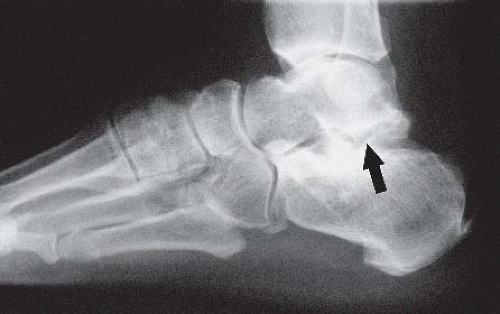

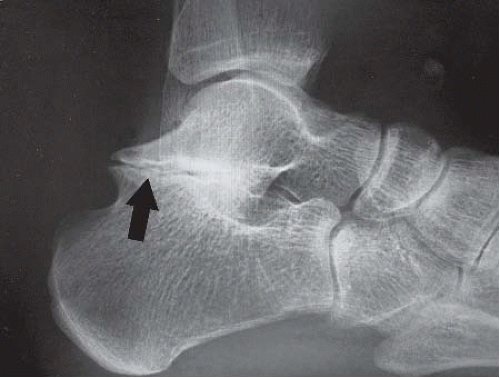

evaluated because of the high incidence of overlapping symptoms. The subtalar joint is best visualized on the lateral view. Subchondral sclerosis, subchondral cysts, osteophytes, and joint space narrowing are common findings in arthritis (Fig. 94.3). Articular incongruities and surgical implants often present in posttraumatic arthritis after a calcaneus fracture. Evidence of T-C coalition includes nonvisualization of the middle facet, dysmorphic sustentaculum tali, shortening of the talar neck, and the C-sign (3,4) (Fig. 94.4). Talar beaking is most commonly seen in T-C coalition (39%) but can be associated with calcaneonavicular coalition (19%) as well (5). A Harris view of the calcaneus can sometimes demonstrate a coalition in the middle facet as well as medial osteophytes. A hindfoot alignment view can give objective evidence of coronal plane deformity of the hindfoot, which may be helpful in surgical planning.

evaluated because of the high incidence of overlapping symptoms. The subtalar joint is best visualized on the lateral view. Subchondral sclerosis, subchondral cysts, osteophytes, and joint space narrowing are common findings in arthritis (Fig. 94.3). Articular incongruities and surgical implants often present in posttraumatic arthritis after a calcaneus fracture. Evidence of T-C coalition includes nonvisualization of the middle facet, dysmorphic sustentaculum tali, shortening of the talar neck, and the C-sign (3,4) (Fig. 94.4). Talar beaking is most commonly seen in T-C coalition (39%) but can be associated with calcaneonavicular coalition (19%) as well (5). A Harris view of the calcaneus can sometimes demonstrate a coalition in the middle facet as well as medial osteophytes. A hindfoot alignment view can give objective evidence of coronal plane deformity of the hindfoot, which may be helpful in surgical planning.

FIGURE 94.2. The patient locates the point of maximum pain corresponding to a bony prominence due to a T-C coalition. |

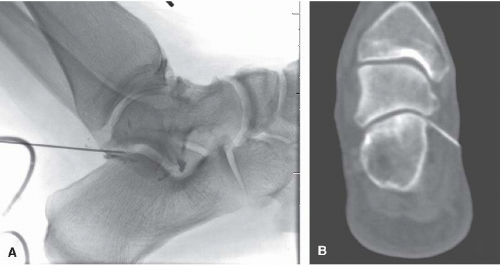

Image-guided injection of local anesthetic agent is particularly useful as a part of making a therapeutic diagnosis

(Fig. 94.5A, B). Injections under fluoroscopic guidance have been shown to be helpful in differentiating pain from the ankle and/or the subtalar joint prior to an arthrodesis. However, the communication between the ankle and the posterior subtalar joint is present in about 10% of patients. Cortisone can be added if the anti-inflammatory effects are desired after risks and benefits have been explained to the patient. Pain relief can be more predictable after a subtalar arthrodesis when all or most of the pain is eliminated immediately after the injection.

(Fig. 94.5A, B). Injections under fluoroscopic guidance have been shown to be helpful in differentiating pain from the ankle and/or the subtalar joint prior to an arthrodesis. However, the communication between the ankle and the posterior subtalar joint is present in about 10% of patients. Cortisone can be added if the anti-inflammatory effects are desired after risks and benefits have been explained to the patient. Pain relief can be more predictable after a subtalar arthrodesis when all or most of the pain is eliminated immediately after the injection.

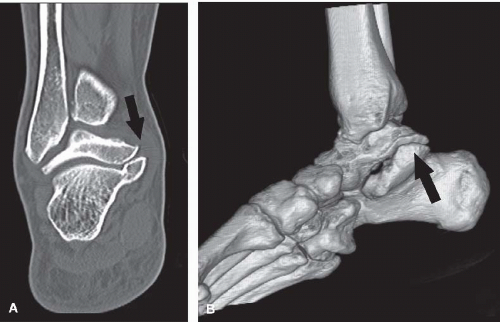

A CT scan can best demonstrate the osseous anatomy of the subtalar joint. It is considered the gold standard for diagnosing a T-C coalition (6). The degree of arthritis can be clearly shown together with periarticular osteophytes and loose bodies (Fig. 94.6A, B). MRI has not been commonly used for the evaluation of the subtalar joint due to availability and cost. However, it has a definitive role in the evaluation of bone edema, stress fracture, and nonosseous coalition (Fig. 94.7).

Decision-Making Algorithms

We have not seen a classification of the subtalar arthritis reported in English literature. Most clinicians rely on the presence of symptoms and the response to nonoperative management to guide further treatments. The subtalar joint is mechanically delicate and can cause substantial pain in spite of minimal radiographic changes (1). On the other hand, severe arthrosis of the subtalar joint may allow little motion and can be asymptomatic. Subtalar arthrodesis is usually the only available option after a failure of nonoperative treatment.

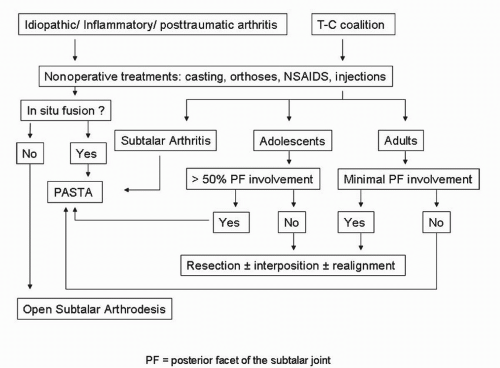

The pathology of the tarsal coalition can be classified into osseous, fibrous, or cartilaginous. The amount of articular involvement can be determined with a CT scan, as the degree of posterior facet involvement has shown association with success after a resection (7). There is no universally accepted protocol in the treatment of T-C coalition. From the available evidence, the resection of coalition is suitable for adolescents with posterior facet involvement of less than 50%; while an arthrodesis is indicated in adolescents with posterior facet involvement greater than 50%, or in patients of any age with arthritis. The treatment in adults with symptomatic coalition without arthritis is inconclusive. We reserve the resection of the T-C coalition for only select cases with minimal involvement of the posterior facet, normal posterior facet joint space, relatively preserved subtalar motion, and absence of tenderness of the lateral subtalar joint. The decision-making algorithms are shown in Figure 94.8.

TREATMENT

Nonoperative Treatment

Nonoperative methods are effective and should be used routinely as first-line treatment, especially for symptomatic T-C coalitions; they have a success rate up to 80%. The goal is to decrease inflammation and mechanical overload of the joint. Anti-inflammatory medication and acetaminophen can be helpful additions. Intra-articular cortisone injections are effective in cases with inflammatory arthropathy such as rheumatoid arthritis, seronegative spondyloarthropathy, systemic lupus erythematosus, and gout. Repetitive injections may accelerate cartilage degradation and increase risk of joint infection. Orthoses are the mainstays of nonoperative treatment (Fig. 94.9). Various types of orthoses with different degree of corrective and accommodative characteristics have been used with the goal of decreasing subtalar motion and normalizing tibial rotation. An optimal amount of medial or lateral forefoot posting can be applied to the orthosis if the deformity is supple. Shoe inserts are generally helpful in shock absorption and mild alignment control. The University of California Biomechanics Laboratory (UCBL) shoe inserts have improved hindfoot control due to their higher trim-lines. Ankle-foot-orthoses and Arizona braces are reserved for cases with severe deformity necessitating a control proximal in the calf. Below-the-knee walking casts or boots are useful as short-term treatment when the pain is severe.

Operative Indications, Timing, and Technique

The most common operative indication for subtalar arthrodesis is intractable pain due to an arthritis or a T-C coalition. Patient should have failed nonoperative treatment for at least 3 to 6 months before considering operative treatment. The surgery can be performed with either an open or an arthroscopic approach. Isolated subtalar arthrodesis by an open approach has been widely used, with a fusion rate of 84% to 100% in primary cases

(8, 9 and 10). The open technique is recommended in a postoperative situation when extensive scar formation prevents arthroscopic access. Lateral extensile exposure also allows surgeons to remove hardware or osseous mass on the lateral side of the calcaneus as well as an opportunity for the realignment calcaneus osteotomy and structural bone grafting to be done (Fig. 94.10). The overall favorable outcome of the open subtalar arthrodesis was mixed with relatively high complication in some series (11, 12 and 13). Arthroscopic approach is advantageous in preserving blood supply to the bone, minimizing soft tissue injury, and decreasing postoperative pain and scarring. The fusion time of the arthroscopic approach is generally shorter than the open technique (9, 14). Although arthroscopic approach has been used mainly for an in situ fusion, a considerable amount of hindfoot alignment can be changed through arthroscopic release and joint debridement. Arthroscopic-assisted arthrodesis, however, requires greater arthroscopic understanding of the anatomy of the hindfoot and some laboratory cadaver training. The posterior facet is the only joint to be fused for most subtalar arthrodeses. It can be approached from either the lateral or the posterior aspect. The lateral approach uses a combination of anterior, middle, and posterior portals for the cartilage debridement in lateral decubitus position (1, 15). We have found it quite difficult to debride the cartilage in the posteromedial aspect of the subtalar joint because of the contour and the tightness of the joint. The posterior approach to the subtalar joint using three posterior portals allows a more direct approach to the entire posterior facet (Fig. 94.11). Access to the posteromedial aspect of the joint is possible due to the release of the posterior T-C ligaments and flexor retinaculum overlying the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon. The addition of posteromedial portal increases the working area in the posterior aspect of the subtalar joint by 45% (16). The alignment of the hindfoot is better controlled in this position and allows straight posterior observation. Indications and contraindications of the arthroscopic subtalar arthrodesis are listed in Table 94.1.

(8, 9 and 10). The open technique is recommended in a postoperative situation when extensive scar formation prevents arthroscopic access. Lateral extensile exposure also allows surgeons to remove hardware or osseous mass on the lateral side of the calcaneus as well as an opportunity for the realignment calcaneus osteotomy and structural bone grafting to be done (Fig. 94.10). The overall favorable outcome of the open subtalar arthrodesis was mixed with relatively high complication in some series (11, 12 and 13). Arthroscopic approach is advantageous in preserving blood supply to the bone, minimizing soft tissue injury, and decreasing postoperative pain and scarring. The fusion time of the arthroscopic approach is generally shorter than the open technique (9, 14). Although arthroscopic approach has been used mainly for an in situ fusion, a considerable amount of hindfoot alignment can be changed through arthroscopic release and joint debridement. Arthroscopic-assisted arthrodesis, however, requires greater arthroscopic understanding of the anatomy of the hindfoot and some laboratory cadaver training. The posterior facet is the only joint to be fused for most subtalar arthrodeses. It can be approached from either the lateral or the posterior aspect. The lateral approach uses a combination of anterior, middle, and posterior portals for the cartilage debridement in lateral decubitus position (1, 15). We have found it quite difficult to debride the cartilage in the posteromedial aspect of the subtalar joint because of the contour and the tightness of the joint. The posterior approach to the subtalar joint using three posterior portals allows a more direct approach to the entire posterior facet (Fig. 94.11). Access to the posteromedial aspect of the joint is possible due to the release of the posterior T-C ligaments and flexor retinaculum overlying the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon. The addition of posteromedial portal increases the working area in the posterior aspect of the subtalar joint by 45% (16). The alignment of the hindfoot is better controlled in this position and allows straight posterior observation. Indications and contraindications of the arthroscopic subtalar arthrodesis are listed in Table 94.1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree