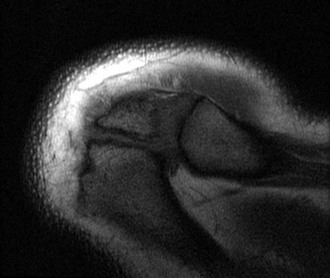

Chapter 28 The concept of shoulder impingement was first described by Meyer in 1937. Later, Neer expanded on Meyer’s work, describing the successive stages of impingement (Box 28-1). Shoulder impingement syndrome is characterized by anterior shoulder pain worsened with overhead activity. Shoulder impingement syndrome is thought to be caused by an anatomic narrowing of the subacromial space by the structures forming the coracoacromial arch leading to progressive bursitis, tendinitis, and rotator cuff tearing. Arthroscopic subacromial decompression has become one of the most common surgical procedures involving the shoulder, both as primary treatment for shoulder impingement syndrome and as a routine practice in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair to create an adequate working space and protect the repair construct. On physical examination of the shoulder, patients with impingement syndrome are said to have positive Neer and Hawkins signs. They may have tenderness to palpation at the greater tuberosity and demonstrate a painful arc syndrome, defined as pain between 60 and 120 degrees of forward elevation in the scapular plane. The infraspinatus test is performed with the patient’s elbows flexed to 90 degrees and the arms adducted to the side. A positive test result is defined as pain and/or weakness when the patient attempts to resist an internal rotation force applied by the examiner. A Neer test may be performed, whereby a diagnostic subacromial injection of 10 mL of lidocaine is provided to assess for relief of symptoms with provocative testing. Park and colleagues reported that the combination of three positive test results—specifically the Hawkins sign, the painful arc sign, and the infraspinatus test result—had a 95% post-test probability for any degree of impingement.1 Multiple physical examination maneuvers to identify AC joint pathology have been described, including direct tenderness to palpation of the AC joint, the cross-arm adduction test, the O’Brien test, and the Paxinos test. An intra-articular diagnostic lidocaine injection remains the gold standard for diagnosis of AC joint pathology, although Partington and Broome demonstrated in a cadaveric study that nearly one third of attempted AC joint injections may be extra-articular.2 In addition to impingement and AC joint arthritis, the differential diagnosis of shoulder pain is broad and includes glenohumeral arthritis, adhesive capsulitis, multidirectional instability, symptomatic os acromiale, biceps tendon pathology, and cervical radiculopathy. One should also be aware that failure to recognize AC joint degeneration and pain concomitant with impingement may lead to a failed subacromial decompression.3 After an initial impression is formed from the history and physical examination, imaging modalities may be used to confirm the diagnosis of impingement or AC joint arthritis or both and to rule out some of the more common causes of shoulder pain often mistaken for these two entities. Radiographs of the involved shoulder should include a true anteroposterior (AP) view of the shoulder (Fig. 28-1), a scapular-Y view (Fig. 28-2), an axillary view, and a Zanca view of the distal clavicle. Magnetic resonance imaging may assist in identifying rotator cuff or labral pathology, AC joint edema, or biceps tendon pathology, as well as an unstable os acromiale (Fig. 28-3). Figure 28-2 Preoperative scapular-Y radiograph of the right shoulder demonstrating a subacromial spur. All patients with impingement should undergo a minimum of 3 to 6 months of nonoperative treatment including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), a subacromial corticosteroid injection, physiotherapy, and modalities. A prospective series by Cummins and colleagues has demonstrated that nearly 80% of patients with symptoms of impingement will have symptomatic resolution without the need for surgery at 2 years of follow-up.4 Nonoperative treatment for AC joint pathology is similar. In addition, activity modification should be encouraged, including cessation of all aggravating activities. Physical therapy may be beneficial in those cases in which impingement and AC joint pain coexist, but it is typically not beneficial in isolated cases of AC joint pathology. For patients with persistent symptoms and functional limitation despite an adequate trial of nonoperative care, shoulder arthroscopy is indicated for management of the pathology. Subacromial decompression and distal clavicle excision can be performed with the patient under regional anesthesia with an interscalene nerve block; with general anesthesia; or with a combined approach. Regional anesthesia can provide enhanced efficiency perioperatively (i.e., block room) as well as improved postoperative pain control, with small associated risks of complications such as intraneural injection, pneumothorax, and cardiac toxicity. Traditionally, hypotensive anesthesia with systolic blood pressure below 100 mm Hg has been advocated to enhance visualization and ease of subacromial decompression. A case series by Pohl and Cullen reported several serious medical complications associated with hypotension, specifically in the upright beach chair position, including stroke and death.5 The practice of deliberate hypotension in the beach chair position should be approached with caution. It is possible to perform each procedure with the patient in either the beach chair or the lateral decubitus position. There are various advantages and disadvantages typically associated with each patient position. One may argue that the lateral decubitus position is more advantageous for a subacromial decompression, as traction on the upper extremity opens up the glenohumeral joint and subacromial space. However, patients in the lateral position do not tolerate regional anesthesia well; thus general anesthesia is required. It is the senior author’s preference to use the beach chair position for both subacromial decompression and distal clavicle excision. This position provides a familiar anatomic orientation, provides for improved access to anterior portal sites, allows easy conversion to an open procedure if required, and lends itself to a regional anesthetic technique.6

Arthroscopic Subacromial Decompression and Distal Clavicle Excision

Preoperative Considerations

Physical Examination

Imaging

Indications and Contraindications

Surgical Technique

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine