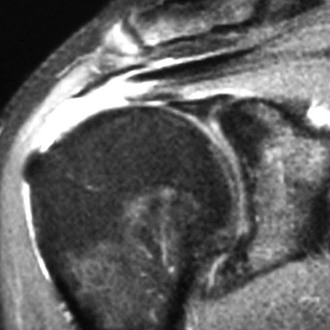

Chapter 20 Although the use of arthroscopic techniques for operative repair of the rotator cuff has become increasingly common, controversy has emerged between advocates of single-row anchor fixation and those who advise use of two such rows (e.g., “double row,” “dual row,” “suture bridge,” “transosseous equivalent”). Proponents of single-row fixation cite decreased cost and decreased operative time and point out the dearth of clinical outcome studies that justify use of double-row techniques. Proponents of double-row fixation, on the other hand, cite biomechanical advantages that include superior repair strength1 and footprint coverage,2 decreased micromotion at the tendon-bone interface,3 and increased, more homogenous pressure distribution across the repair site.4 All of these factors, they suggest, may translate into improved healing potential at the tendon-bone interface. More recently, arthroscopic non–anchor-based transosseous techniques have been developed and may hold significant promise, but for the time being they remain out of mainstream practice. • Distant or recent traumatic event, most commonly a fall from standing height with subsequent temporary inability to actively abduct the arm away from the side • Difficulty with overhead activity secondary to pain and/or “quick” fatigue • Difficulty with outstretched activity secondary to pain and/or quick fatigue • Observable atrophy in the supraspinatus and/or infraspinatus fossae (large or chronic tears) • Tenderness to palpation over the anterolateral shoulder or greater tuberosity • Reproducible anterolateral or lateral shoulder pain on manual motor testing of the rotator cuff • Weakness with manual motor testing of the rotator cuff (large or chronic tears) • Positive “hornblower’s sign” with massive posterolateral tears (inability to actively externally rotate with the arm supported in 90 degrees of abduction) • Plain radiographs consisting of Grashey, outlet, and axillary views for the following: – Evidence of greater tuberosity fracture when a history of trauma is present. – Acromial morphology including identification of enthesophyte on outlet view and os acromiale on axillary view. – Presence of static superior migration of the humeral head with respect to the glenoid. Note that the presence of such static changes together with a large or massive tear serves as a relative contraindication to operative repair. Superior static migration is the condition to look for on plain radiographs. Presence of a massive tear is inferred from the presence of observable static migration. – Presence of degenerative, chronic changes such as osteophyte formation along the inferior anatomic neck of the humeral head, acetabularization of the undersurface of the acromion, sclerosis and “rounding off” of the greater tuberosity, narrowing of the glenohumeral joint space, and loss of sphericity of the humeral head. • Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the following: – Identification of tear size, degree of retraction, tendon quality, and presence of intratendinous delamination and potentially recognition of tear pattern (Fig. 20-1). – Quantification of associated muscle belly atrophy and fatty infiltration. Note this is best performed on T1-weighted sagittal oblique views at the first cut in which the scapular spine becomes visible and can be useful in determining the reparability of the tear. – Identification of associated, potentially surgical pathology such as acromioclavicular arthritis or osteolysis, partial-thickness tearing or subluxation of the long head of the biceps tendon, articular cartilage defects, labral pathology, calcific tendonitis, intra-articular loose bodies, and subscapularis pathology. • Acute, traumatic full-thickness tear in an active, otherwise healthy individual capable of complying with postoperative protocol. • Full-thickness tear with associated, appropriate pain recalcitrant to nonoperative treatment. Note that pain out of proportion to objective findings and/or pain in a distribution inconsistent with rotator cuff pathology should prompt further diagnostic investigation and consideration of alternative diagnoses such as complex regional pain syndrome and cervical spine disease. • Concomitant adhesive capsulitis (relative) • Complex regional pain syndrome • Changes consistent with rotator cuff tear arthropathy (e.g., static proximal migration of the humeral head on plain radiography) • Stage 4 fatty infiltration with significant muscle belly atrophy and significant tendon retraction (e.g., to glenoid rim) (relative)

Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair

Single-Row Technique

Preoperative Considerations

Physical Examination

Imaging

Indications and Contraindications

Contraindications

Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair: Single-Row Technique