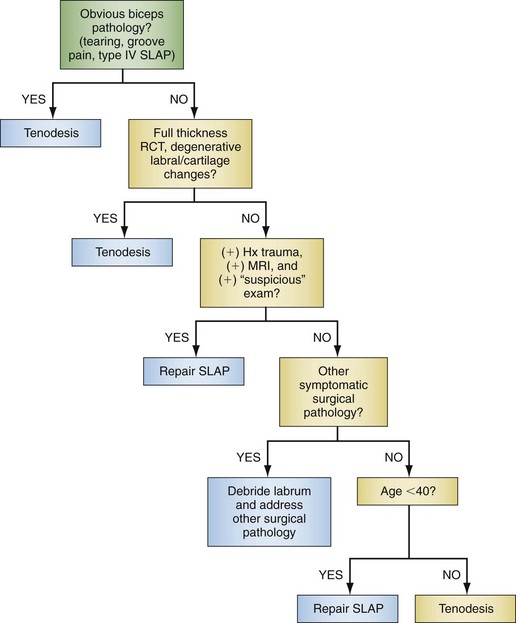

Chapter 26 Tears of the superior labrum were first described by Andrews and colleagues in 19851 and later named and classified by Snyder and colleagues in 1990.2 Since that time, the treatment of superior labral anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesions has evolved from debridement to repair using drill holes, tacks, and now suture anchors. With minor variations in technique only, most surgeons currently advocate the use of one or more suture anchors on the edge of the glenoid to stabilize and restore labral and biceps anchor anatomy. With only level III and IV evidence available in the literature, and a good deal of confusion regarding accurate diagnosis of a symptomatic SLAP lesion, there is still a great deal to be learned. Over the past 25 years, we have been working to develop a better understanding of SLAP lesions. This chapter represents our current management strategy. A thorough history is essential in elucidating an injury to the superior labrum. Typically the patients are young male athletes who report shoulder pain exacerbated by overhead activity, or male or female patients who have sustained a traumatic traction or compression injury to the shoulder.2,3 This is often associated with popping, snapping, catching, or locking, similar to mechanical symptoms that may be associated with a meniscal tear in the knee.4,5 SLAP lesions must be differentiated from other pathologic processes of the shoulder, such as instability, impingement, rotator cuff tear, and acromioclavicular joint disease. Without a clear history of throwing overuse or trauma, the diagnosis must be questioned. Unfortunately, there is no single physical examination test that is specific and sensitive for a SLAP lesion, although several have been described. Both the comprehensive physical examination and the history are essential in raising the index of suspicion for a possible SLAP lesion. A complete examination is important but not accurate in predicting with certainty the existence of a SLAP lesion, although there are several tests that may prove useful. The biceps tension (Speed) test was the most accurate in several studies.6–8 The Speed test result is positive when pain is elicited with resisted forward elevation of the fully supinated arm with the elbow extended and the arm flexed to 90 degrees. The compression-rotation sign described by Andrews and colleagues9 is demonstrated with the patient supine, the shoulder elevated to 90 degrees, and the elbow flexed to 90 degrees. An axial load is then applied to the humerus to compress the glenohumeral joint while the arm is rotated. A positive test result is pain as well as mechanical symptoms elicited during this test. The O’Brien sign, or the active compression test, is elicited by first placing the arm in 90 degrees of forward flexion and 10 to 20 degrees of adduction. The arm is then fully internally rotated into the thumb-down position. The patient is then asked to resist downward pressure to the arm that is applied by the examiner. Pain is often produced when an unstable superior labrum is present. The test is then repeated but with the arm in full supination; the pain should be decreased in this position compared with the initial position for the test result to be considered positive. We consider mechanical pain and one or more positive provocative tests to be consistent with a “suspicious physical examination.”10 Although very high–quality magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines and very experienced evaluators may not need gadolinium-enhanced arthrograms to achieve similar sensitivity, MRI with arthrogram is still the most reliable imaging test of choice. Normal anatomic variations around the superior labrum can make MRI findings nonspecific, and the gold standard in diagnosing SLAP lesions is still arthroscopy itself, but the presence of paralabral cysts and coronal images with contrast extension under the superior labrum and extending laterally into the substance of the labrum are most commonly associated with true SLAP lesions (Fig. 26-1). MRI is also useful to evaluate for concomitant pathologic changes, such as rotator cuff tears, acromioclavicular joint disease, and biceps disease. A combination of knowledge of anatomy (anatomic variants), patient history (traumatic event, overhead athlete), physical examination findings (“suspicious” provocative test results), MRI findings (contrast into labral tissue), and arthroscopy findings (detached unstable labrum and biceps anchor) with no other obvious explanation for the symptoms will give the best chance to correctly diagnose a SLAP lesion. Diagnostic arthroscopy is indicated when a SLAP tear is suspected in a symptomatic patient in whom a course of nonoperative treatment has failed but who otherwise has the corresponding history, physical examination, and MRI findings. Indications for repair are still being defined. We have developed and published an algorithm that can assist in the decision-making process (Fig. 26-2).10

Arthroscopic Repair of Superior Labral Anterior-Posterior Lesions by the Single-Anchor Double-Suture Technique

Preoperative Considerations

Physical Examination

Imaging

Indications and Contraindications

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Arthroscopic Repair of Superior Labral Anterior-Posterior Lesions by the Single-Anchor Double-Suture Technique