Arthroscopic Reconstruction of the Coracoclavicular Ligaments for Acromioclavicular Dislocations

Eugene M. Wolf MD

Austin T. Fragomen MD

History of the Technique

Dislocations of the acromioclavicular (AC) joint have been recognized as significant sports-related shoulder injuries since the time of Hippocrates. Thorndike and Quigley1 observed that these dislocations compromised more than one third of all shoulder injuries in the over 500 athletes that they studied. Most trauma to the AC joint results in an incomplete joint dislocation (Rockwood types I and II) whose acute treatment is universally nonoperative. When the displacement of the clavicle is complete (Rockwood types III through VI), the preferred treatment varies greatly. Good results have been reported with conservative management of these injuries.2 However, experience has taught us that there exist a significant number of patients who benefit from operative intervention.

Arthroscopic reconstruction of the coracoclavicular ligaments was created to introduce a less invasive alternative for the anatomic reconstruction of the conoid and trapezoid ligaments. It was designed to provide stability and pain relief to patients with symptomatic complete AC joint dislocations while simultaneously achieving a superior cosmetic result. The technique has evolved since the publication of the original description in 2001.3 With the development of reliable instrumentation, strong and resilient implants, and reproducible techniques, arthroscopic coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction has proven to be an attractive method for treating AC joint dislocations.

The arthroscopic acromioclavicular reconstruction is a reproducible, minimally invasive technique well suited for orthopedic surgeons with experience in arthroscopic shoulder surgery. This technique provides an anatomic reconstruction of the coracoclavicular ligaments with the goal of restoring normal shoulder kinematics. It has been observed that scapulothoracic and acromioclavicular malalignment lead to symptomatic shoulder dyskinesis in patients who sustain high-grade shoulder separations (dislocation). This technique will restore a strong coracoclavicular construct while preserving coracoid and clavicular bone. The arthroscopic nature of this procedure allows for a rapid rehabilitation and a full return to preinjury activities.

Indications and Contraindications

Arthroscopic AC joint reconstruction is indicated for Rockwood type IV through VI AC joint separations and for certain Rockwood type III separations: chronic AC joint separations that are painful and result in a dysfunctional shoulder girdle with significant deformity, and acute AC joint separations in active patients who are unwilling to accept any deformity, dysfunction, or pain in the affected shoulder.

Rockwood type I and type II separations are typically treated nonoperatively. Distal clavicle resection alone may be indicated in select cases with painful degeneration of the AC joint. Patients who remain asymptomatic and have no cosmetic concerns are not indicated for surgery regardless of the severity of injury. Patients who cannot follow a postoperative rehabilitation protocol are not candidates for this surgery. A relative contraindication is advanced age. Poor bone quality in older patients may compromise the reconstruction effort. The oldest patient to have received this operation was 67 years old, and he obtained an excellent result at his 3-year follow-up examination.

Patients typically complain of pain, popping, a sensation of instability, and/or deformity in the region of the AC joint. The grade of separation may not be directly proportional to the level of complaints from a patient. A minimally displaced

separation may be more painful and disabling than a high-grade separation. Similarly, once a chronically separated distal clavicle is reduced and contacts the acromion, the potential exists for creating a painful, anatomically reduced AC joint. Any painful AC joint must undergo a distal clavicle resection, either open or arthroscopic, at the time of reconstruction. In light of the sensitivity of the AC joint, it is strongly recommended that a distal clavicular resection be performed routinely with any coracoclavicular reconstruction. Two centimeters of distal clavicle should be removed to ensure that there will be no contact with the acromion. This will also provide the best aesthetic result.

separation may be more painful and disabling than a high-grade separation. Similarly, once a chronically separated distal clavicle is reduced and contacts the acromion, the potential exists for creating a painful, anatomically reduced AC joint. Any painful AC joint must undergo a distal clavicle resection, either open or arthroscopic, at the time of reconstruction. In light of the sensitivity of the AC joint, it is strongly recommended that a distal clavicular resection be performed routinely with any coracoclavicular reconstruction. Two centimeters of distal clavicle should be removed to ensure that there will be no contact with the acromion. This will also provide the best aesthetic result.

The acromioclavicular separation must be evaluated preoperatively to determine the degree of separation of the joint and its reducibility. Preoperative weighted stress radiographs are obtained in the office, and the amount of superior displacement of the distal clavicle is evaluated by measuring the coracoclavicular distance. Only Rockwood type III through VI AC joint separations are considered for reconstruction. The AC joint should be tested for ease of reduction. An irreducible joint indicates the presence of interposing scar tissue that will have to be removed intraoperatively.

Surgical Technique

General anesthesia is routinely administered to patients for all arthroscopic shoulder procedures at our institution. Alternatively, brachial plexus blocks in conjunction with sedation have been used with success. This technique may be performed in the lateral decubitus position or in the beach chair position.

The bony landmarks of the shoulder are outlined with a sterile marker to include the distal clavicle, the coracoid, and the acromion, and the proposed portal sites are marked. A standard posterior portal is created for the insertion of a 30-degree arthroscope into the glenohumeral joint. An anterior inferior portal is created 2 to 3 cm lateral to the tip of the coracoid. The portal is created with an outside-in technique by first placing a spinal needle in the rotator cuff interval and entering the joint at the superior margin of the subscapularis tendon. An incision is made adjacent to the needle and a clear 8.25 mm by 7 cm Twist-In Cannula (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, Fla) with reusable obturator is advanced into the joint. This cannula will serve as the primary working portal.

Visualization of the coracoid is the goal of this portion of the procedure. This will require resection of the rotator interval capsule, including the superior glenohumeral and part of the middle glenohumeral ligaments.

The resection of the rotator interval capsule begins by backing out of the anterior inferior cannula to a position just outside the capsule. An arthroscopic shaver is used to remove rotator interval tissue until the coracoid is well visualized. A radiofrequency wand is used to control bleeding.

The anterior superior portal is then created at a point just anterior to the anterior margin of the acromion. A spinal needle enters the joint immediately anterior to the biceps tendon. A no. 11 scalpel blade is directed into the joint adjacent to the spinal needle to create a path through the rotator cuff. The scalpel is withdrawn and a switching stick is inserted into the newly created anterior superior portal (ASP). The arthroscope is transferred to the ASP and a 5-mm cannula is placed in the posterior portal

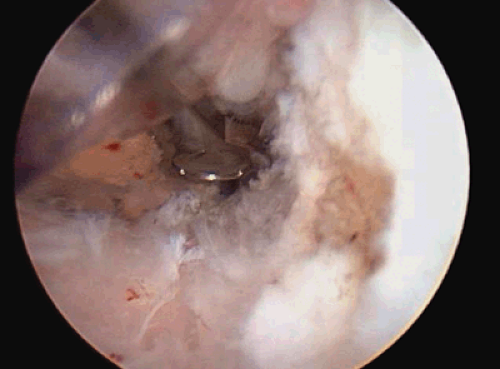

This configuration allows direct visualization of the base of the coracoid and anterior scapular neck. With the arthroscope in the ASP, a radiofrequency wand and shaver are used to define the base of the coracoid as far medially as possible (Fig. 15-1).

Fig. 15-1. View of the base of the coracoid and anterior scapular neck from ASP with probe in place. |

In cases of chronic acromioclavicular dislocations, it may be necessary to extend the arthroscopic dissection medially to resect the scar tissue between the coracoid and the clavicle. The surgeon may opt to perform an open distal clavicle resection, since a small incision over the distal clavicle will

be necessary at the terminal portion of every case. A 2-cm incision is made in the Langer lines over the superior aspect of the distal clavicle. The skin is undermined and mobilized. The soft tissues on the superior surface of the clavicle are elevated subperiosteally. The distal 2 cm of clavicle are removed and morselized for later use as bone graft.

be necessary at the terminal portion of every case. A 2-cm incision is made in the Langer lines over the superior aspect of the distal clavicle. The skin is undermined and mobilized. The soft tissues on the superior surface of the clavicle are elevated subperiosteally. The distal 2 cm of clavicle are removed and morselized for later use as bone graft.

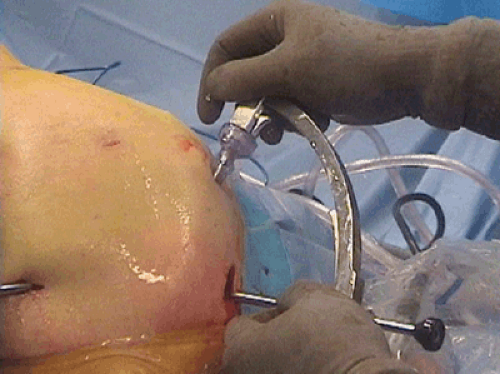

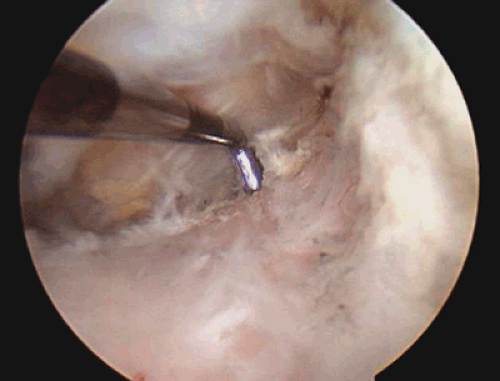

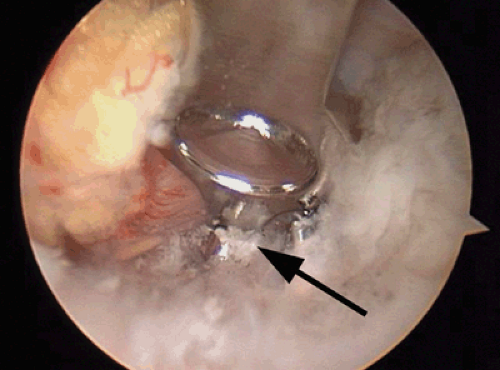

The Sub-Coracoid Drill Guide (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, Fla) on an Adapteur C-ring Drill Guide (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, Fla) is selected. The Sub-Coracoid Drill Guide is placed through the anterior inferior cannula onto the inferior surface at the base of the coracoid (Fig. 15-2). The 8.25-mm clear cannula is advanced to the “axilla” of the coracoid base so as not to limit the medial excursion of the Sub-Coracoid Drill Guide. The probelike tip of the guide is advanced medially until it falls off the medial border of the base of the coracoid. This will center the drill hole in the stronger, wider coracoid base. Traction is released and the clavicle reduced. The resected end of the distal clavicle is identified. The drill sleeve on the Adapteur C-ring Drill Guide is then advanced onto the superior aspect of the reduced distal clavicle (Fig. 15-3). With a clear arthroscopic view of the Sub-Coracoid Drill Guide, a 2.4-mm Drill-tipped Guide Pin (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, Fla) is drilled through the clavicle and the base of the coracoid. The tip of the Guide Pin is viewed as it exits the base of the coracoid (Fig. 15-4). The guide is left in place and a 4.5-mm cannulated drill is used over the Guide Pin to create a tunnel through the clavicle and the base of the coracoid. When the tip of the drill bit is seen exiting bone it is stopped and left in place.

Fig. 15-4. View from ASP of coracoid drill stop portion of the Sub-Coracoid Drill Guide catching Drill Tipped Guide Pin as it exits coracoid base.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|