Fig. 14.1

Sagittal view of the preoperative PCL. a Top MRI reveals the proximal avulsion, the ligament is still intact at the tibia but avulsed from the femur (white arrow). b Bottom MRI shows distal avulsion, the ligament is still intact at the femur but avulsed from the tibia (black arrow). PCL posterior cruciate ligament, MRI magnetic resonance imaging. (From Lissy et al. 2012 [33, p. 195]. Reprinted with permission)

When reading the MRI , in general, one end of the ligament will appear rather normal at its insertion to bone, and have a large percentage of the ligament that has a relatively “normal” homogeneous signal appearance. It is not uncommon for there to be significant heterogeneity of signal with proximity to the zone of injury at the avulsed end. Unfortunately, no standard has been established as to exactly what appearance is predictive of possible repair. An MRI evaluation will simply give the surgeon an idea that primary repair may be possible at surgery. Ultimately, tissue length and quality at surgery will determine if this procedure has a chance of success. Anecdotally, the MRI is only moderately predictive of which tears will eventually be reparable.

Senior Author’s Preferred Surgical Technique

It should be noted that the description of this technique will discuss the repair of a femoral soft tissue avulsion. This is the more common and technically easier repair to perform.

Prior to entering the operating room (OR), the surgeon must assure that the proper equipment is available. Standard knee arthroscopy equipment complimented by some select equipment from the shoulder arthroscopy sets will be required. In particular, large bore, malleable cannulas (PassPort-Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA), a reloadable suture-passing device (Scorpion FastPass-Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) and/or other suture-passing devices, and a high-grade polyester suture (#2 Fiberwire-Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA). Depending on the choice of fixation, the surgeon would also need knotless suture anchors (4.75 BioComposite Swivelock-Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) with their associated punches and taps, or a cannulated drill (RetroDrill-Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) and a standard ligament button.

The setup does not necessitate a deviation from the surgeon’s preferred arthroscopy setup as long as access to the knee is not limited. A leg holder for the opposite leg, however, does help in allowing access to accessory posterior portals that are necessary if addressing tibial-sided avulsions. Standard arthroscopic portals are created and a diagnostic tour of the knee is initiated. The PCL stump must be identified and mobilized by gently freeing it from any scar tissue (Fig. 14.2) that typically will form to the ACL or its remnant depending on the injury pattern. Once mobilized, the surgeon must ensure that there is adequate length for repair and that the ligament tissue is of sufficient quality to hold the stitches. It is important to utilize a broad grasper (Cuff Grasper, Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) when assessing the ligament so as to avoid further damage to the ligament remnant (Fig. 14.3). When assessing length, it is critical to remember to reduce the knee so that the anterior tibia is 1 cm anterior to the femoral condyles when the knee is flexed at 90°. If the tibia is sagging posteriorly as is common, and the tibia is not reduced, then the PCL will give the appearance that it does not have the appropriate length to reach the wall for primary repair. With a tibial reduction maneuver, a more accurate assessment of length can be made. Once a decision has been made to attempt a primary repair, and prior to passing sutures through the ligament, it is advisable to dilate the medial portal and insert the malleable cannula. It should also be noted that if addressing a tibial avulsion, posteromedial and/or posterolateral accessory portals will be necessary.

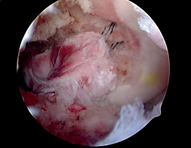

Fig. 14.2

Initial arthroscopic view of the PCL stump prior to debridement. PCL posterior cruciate ligament

Fig. 14.3

Assessment of the ligament length

The next, and generally the most technically demanding aspect of the procedure, is suture passage through the remnant. Using a reloadable suture-passing device, as would be utilized for a rotator cuff repair, high-tensile suture is passed through the ligament stump and autoretrieved via the trapdoor mechanism on the opposite jaw (Fig. 14.4). It is important to start the first pass as close as possible to intact insertion of the ligament stump so as to maximize the number of locking throws that can be placed into the ligament. Once the first pass is made, the suture is retrieved and the suture limbs are equalized. Each limb of the suture is then passed back through the ligament; alternating suture limbs and the direction of the suture pass gradually progressing along the length of the stump towards the avulsion. This creates an interlocking suture pattern akin to the Bunnell stitch. It is imperative that the previously passed suture is not cut during subsequent passes. This is avoided by monitoring tissue resistance. If resistance is encountered on an attempted pass, the pass should be aborted. The suture passer can then be repositioned and another attempt can be made. There should be little resistance during passage through the tissue.

Fig. 14.4

The Scorpion® (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) suture passer is used to pass the #2 Fiberwire (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) into the PCL. PCL posterior cruciate ligament

If individual bundles are identified and isolated, they may be addressed separately; otherwise, the sutures are passed without regard to bundles. Effort should be expended on having the final suture passes exit the torn end of the tendon towards the wall. Typically, two high-tensile sutures are passed per repair resulting in four free limbs of suture exiting the avulsed end of the tendon. Occasionally, with larger patients, it is possible to get two sutures into each bundle, resulting in eight free limbs for repair (Fig. 14.5). Meticulous suture management, utilizing accessory portals, and the malleable cannula are necessary to avoid tangles and soft tissue bridges.

Fig. 14.5

An arthroscopic view of a double-bundle repair of the PCL with sutures passed, prior to fixation. PCL posterior cruciate ligament

With the suture limbs “parked” out of the way, either out an accessory portal or outside the cannula, they can be gently tensioned to retract the ligament remnant and protect it during preparation of the repair bed. Then, using either an arthroscopic shaver or a burr according to surgeon preference, the insertional footprints can be debrided to create a bed of bleeding bone.

At this point, the technique deviates depending on the choice for fixation. However, regardless of the technique, a precise understanding of the insertional footprint is critical. The goal is to attempt to recreate the anatomic attachments of both the anterolateral and posteromedial bundles. If knotless anchors are used, the steps are slightly different than if the repair is to be tied over a button. First, the arthroscope must be placed in the anteromedial portal to facilitate the angle of approach that is necessary for placing the anchors into the medial femoral condyle from lateral. Next, coming through the anterolateral portal the first anchor hole is made into the anterolateral bundle origin using a drill, awl, and/or tap according to bone quality and surgeon preference. The appropriate sutures are then inserted into the knotless anchor and the anchor is deployed into the medial femoral condyle in standard fashion reapposing the anterolateral bundle to the bone. The knee is held at 90° with an anterior drawer force on the tibia during fixation. This process is then repeated to place the anchor reattaching the posteromedial bundle origin.

If fixation is to be performed by tying over a bone bridge, then the procedure is slightly different. A PCL femoral guide is placed through the medial portal and used to guide the cannulated drill into the origin of the anterolateral bundle. A small incision is made medially over the femoral condyle to advance the guide down to bone. Once the drill is passed, a nitinol-passing wire is shuttled through the cannulation of the drill, retrieved out of the cannula, and used to shuttle the appropriate repair stitches through the femoral condyle (Fig. 14.6). This procedure is then repeated for the posteromedial bundle. After shuttling all of the suture limbs out their respective bone tunnels, they are passed through the ligament button and tied with an anterior drawer force being applied to the tibia. Alternatively, a 2.4-mm drill bit and spinal needles can be used to pass the nitinol wire, or the suture limbs can be tied to a post depending on surgeon preference. Reduction of the ligament to its insertion during fixation with the knee in 90° of flexion should be visualized with the arthroscope. Once fixation is completed, the ligament should be gently probed to confirm integrity of the repair, and a gentle posterior drawer can be performed to evaluate the improvement in posterior laxity afforded by the repair.

Fig. 14.6

PCL repair through drill holes prior to tensioning. PCL posterior cruciate ligament. (From Lissy et al. 2012 [33, p. 205]. Reprinted with permission)

Postoperative Management

Postoperative management will be variable and depend on whether this was an isolated repair or in conjunction with a multiligament reconstruction. Confidence in the PCL repair will determine the duration of immobilization prior to beginning range of motion (ROM) exercises. Typically, a hinged knee brace locked in extension is placed in the operating room. Protected weight bearing is recommended with crutches and close attention is paid to edema control and cold therapy. Immediate quadriceps isometrics in extension are encouraged to restore control of the limb. Gentle progressive ROM exercises can be initiated between 2 and 4 weeks postoperatively, again depending on surgeon preference and confidence in the repair. Progression will be dictated by the clinical situation. Active hamstrings should be avoided for 4–6 months.

Case Examples

Case #1: Repair of a PCL Femoral Avulsion in a 67-Year-Old Female with a Knee Dislocation-3 Lateral MLIK

A 67-year-old female suffered an isolated, low-energy, KD-3 lateral knee dislocation after a trip and fall. She was manually reduced in the emergency room (ER), and throughout her post-injury course she had normal neurovascular exams. She was splinted and admitted for neurovascular checks. An MRI revealed that her injury pattern included what appeared to be complete proximal avulsions of both cruciates, and an arcuate fracture resulting in gross laxity in multiple planes on clinical exam (Fig. 14.7).

Fig. 14.7

a and b AP and lateral injury radiographs showing anterior knee dislocation. AP anteroposterior

After several days of observation, the patient was discharged in a locked hinged knee brace. She was allowed protected weight bearing and instructed in edema control. Close follow-up confirmed maintenance of neurovascular stability and gross instability of the knee to anterior and posterior drawer and to varus in extension. Surgical intervention was recommended with a plan for attempted arthroscopic open repair versus allograft reconstruction of the cruciates, and open repair versus allograft augmentation/reconstruction for the lateral side. Given the injury patterns, and her age, the hope was to minimize the surgical insult by primarily repairing the injured structures wherever possible (Fig. 14.8). Surgery was performed at 2.5 weeks post injury.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree