Arthroscopic Meniscus Repair

Hussein A. Elkousy MD

Freddie H. Fu MD, DSc, DPs (Hon)

History of the Technique

Thomas Annandale performed the first meniscus repair in 1883. However, the technique was ignored mostly due to the perceived minor role that the meniscus plays in normal knee function. Several studies have subsequently proven the importance of the meniscus in normal knee function and documented the adverse sequelae of meniscectomy over time.1,2,3,4 The menisci are now known to play important roles in joint lubrication, shock absorption, proprioception, articular cartilage nutrition, secondary stabilization, and load transmission.1,5 As a result, several techniques were developed to repair, rather than to excise, a torn meniscus. An open technique was reported by DeHaven et al.6 to have successful results, but arthroscopic techniques have become the standard. The first arthroscopic meniscus repair was done in Japan in 1969 by Ikeuchi.7,8

Arthroscopic meniscus repair can be broadly divided into three different techniques: inside-out, outside-in, and all-inside. Inside-out techniques use specially designed cannulae to pass sutures through the meniscus from the inside to the outside of the joint. This technique was introduced in North America in 1980 by Charles Henning.7 The outside-in technique uses spinal needles or cannulae to pass sutures through the meniscus from outside the joint to the inside. This technique was popularized by Russell Warren in the 1980s.9 The all-inside technique does not require any external incisions and all fixation is performed arthroscopically. This technique has changed significantly since its original descriptions in the early 1990s.1,10

This chapter will primarily discuss inside-out and outside-in techniques. We prefer the inside-out technique and will focus on this technique, but both are useful for successful repair of a torn meniscus. All-inside techniques vary due to the large number of devices manufactured by different vendors, but a short summary of all-inside techniques will be included.

Indications and Contraindications

Meniscus repair has two goals. First, it should relieve pain and allow the patient to return to his or her previous level of activity. Second, it theoretically preserves the function of the meniscus and minimizes future degenerative changes. The first goal can equally be achieved with partial meniscectomy.11 However, it is the second goal that holds promise for meniscus repair. Several studies have been done to evaluate meniscus repair, but only a few have shown that it prevents future degenerative changes.6,12,13

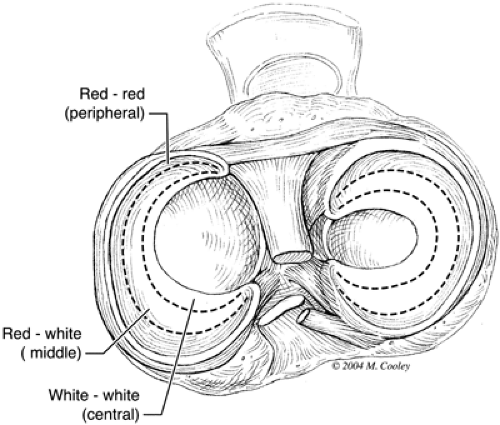

Not every torn meniscus is amenable to repair. Certain parameters have been defined that help predict which tears can be repaired with a reasonable expectation for a successful result.5,14 First, the tear should be in a well-vascularized area. Arnoczky and Warren15,16 defined the zones of the meniscus based upon vascularity (Fig. 50-1). The peripheral 10% to 25%, termed the red-red zone, is supplied by a perimeniscal capillary plexus. The middle third is the red-white zone, and the central third is the white-white zone. The poor blood supply of these more central zones limits the healing potential of more central meniscus tears. Second, longitudinal tears have a higher rate of healing than radial, horizontal cleavage, or other complex tears. Bucket handle tears are a subset of longitudinal tears. Third, the knee must be stable. Meniscus repairs tend to fare poorly in anterior cruciate ligament–deficient knees, and improved outcomes are seen with concomitant anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction.16,17,18 Fourth, most candidates for repair are below the age of 40.5,14 Some studies have demonstrated successful

outcomes in older populations.18,19 However, the potentially limited benefit over partial meniscectomy should be carefully weighed in this older population considering the likely presence of articular cartilage changes, the hardships of rehabilitation, and the poorer quality of tissue and inferior blood supply. Finally, acute tears have a higher rate of healing than chronic tears.14

outcomes in older populations.18,19 However, the potentially limited benefit over partial meniscectomy should be carefully weighed in this older population considering the likely presence of articular cartilage changes, the hardships of rehabilitation, and the poorer quality of tissue and inferior blood supply. Finally, acute tears have a higher rate of healing than chronic tears.14

Inside-out Meniscus Repair

Anesthesia

We generally use general endotracheal anesthesia. The patients who are candidates for meniscus repair are otherwise young and healthy; therefore, they generally have few risk factors that preclude this. A lower extremity regional nerve or plexus block is not unreasonable, but we cannot see any particular advantage to this at the present time, unless the ACL is reconstructed at the same sitting. Postoperative pain is generally adequately controlled with oral narcotics. In addition, some surgeons may infiltrate a local anesthetic such as Marcaine perioperatively to augment analgesia. We tend to avoid postoperative injections that may disrupt the internal milieu of the joint, particularly if fibrin clot is used.

Surface Anatomy and Skin Incision

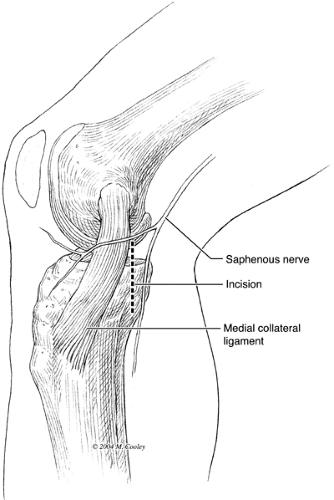

The skin incision is marked at the beginning of the case prior to placing the arthroscope. The skin incision for a medial meniscus repair is placed just posterior to the medial collateral ligament (Fig. 50-2). This site is approximated on the skin by first placing the knee in 90 degrees of flexion. The medial joint line is marked by identifying and marking the lateral joint line and extrapolating this line medially. The medial joint line can sometimes be difficult to identify directly. As this line is directed posteriorly, care should be taken to re-create a small amount of posterior slope that is most certainly present. Next, the posteromedial border of the tibial diaphysis is palpated. A line is projected proximally and in-line with the diaphysis. This is the vertical line defining the anteroposterior position of the incision. A 3-cm to 4-cm incision is marked with one third of the incision proximal to the joint line and two thirds distal to the joint line.

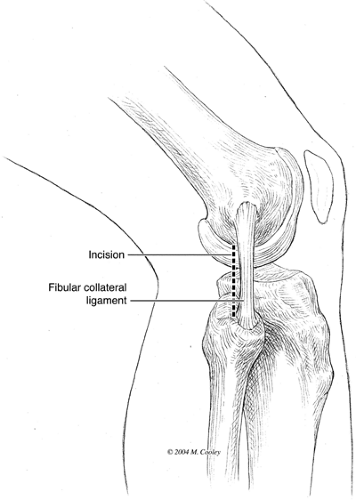

The lateral incision is marked by placing the knee in 90 degrees of flexion and marking the joint line as for the medial side. The lateral collateral ligament and the fibular head are palpated and a vertical incision is marked along the posterior border of the lateral collateral ligament (Fig. 50-3). The incision does not extend further distal than the tip of the fibular head. It is also placed one-third above and two-thirds below the joint line.

Deep Anatomy

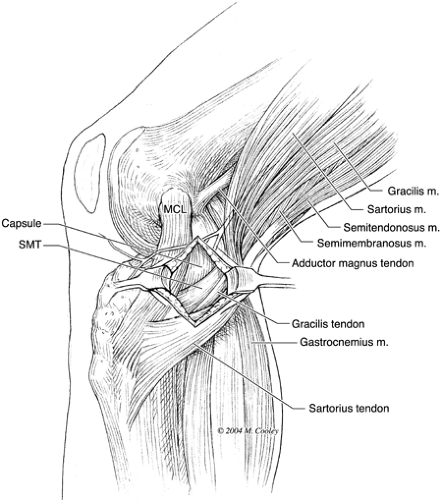

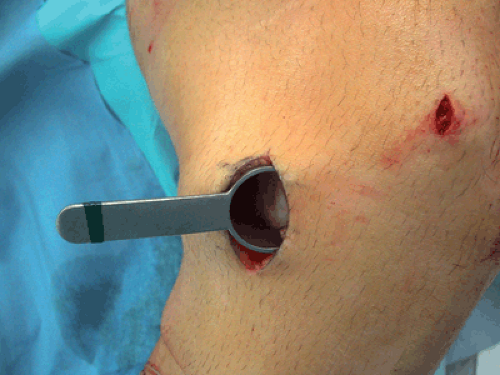

The medial and lateral approaches require dissection through two layers of tissue. The superficial layer includes the skin, fat, and superficial fascia. The second layer on the medial side includes the pes anserine fascia proximal to the sartorius fascia (Fig. 50-4). The superficial medial collateral ligament should be anterior to the plane of dissection. The retractor is placed superficial to the deep medial collateral ligament and the capsule (Fig. 50-5). The structure at risk with this approach is the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve (Fig. 50-6).

Once the skin and superficial fascia are incised on the lateral approach, the iliotibial (IT) band and biceps femoris are identified (Fig. 50-7). The plane of dissection remains anterior to the biceps femoris and extends to the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle. The retractor is placed between the lateral head of the gastrocnemius and the capsule. The structure most at risk with this approach is the peroneal nerve. However, this should not be an issue as long as the dissection remains anterior to the biceps femoris.

Surgical Details

Once the patient is asleep, the knee is examined. If there is any question of stability, this should be evaluated with a thorough exam under anesthesia. Additional procedures such as ACL reconstruction should have been discussed with the patient preoperatively. If an ACL reconstruction is to be performed, the meniscus repair sutures are passed prior to ACL reconstruction, but they are not tied until after the ACL reconstruction is complete.

Potential medial and lateral incisions are marked as described in the section on superficial anatomy. This can be done after the knee is cleaned with Betadine solution and

draped, but we prefer to do this initially. The knee is then prepared and draped in sterile fashion.

draped, but we prefer to do this initially. The knee is then prepared and draped in sterile fashion.

Fig. 50-6. Infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|