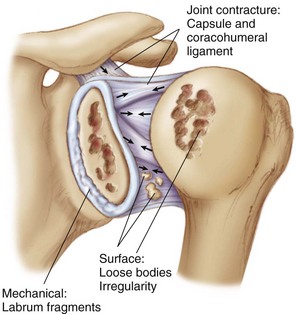

Chapter 29 Glenohumeral degenerative disease is a growing problem in the relatively young, active patient population. Patients with shoulder arthritis have increased pain and decreased function compared with patients with normal shoulder joints,1 and such symptoms can certainly have a significant impact on quality of life, particularly at a younger age. However, given the complexity of the shoulder joint, it can be difficult to determine the exact pain generator (Fig. 29-1). Articular cartilage degradation can contribute to the patient’s symptoms, as can other shoulder pathologies including synovitis and capsulitis, labral tears, rotator cuff pathology, and long head of the biceps (LHB) tenosynovitis. Thus a comprehensive diagnostic and therapeutic approach is necessary. Nonoperative treatment techniques including activity modification, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and intra-articular injections of corticosteroids and/or hyaluronic acid solutions (off-label use) are typically effective as first-line options; however, their effects are often temporary.2,3 Surgical options are varied and range from simple arthroscopic debridement to total shoulder arthroplasty. Arthroplasty has certainly shown favorable outcomes with regard to pain relief; however, postoperative limitations and risks can be significant in an active patient. Nonarthroplasty alternatives, including arthroscopic debridement, are increasingly attractive options in contemporary orthopedics.4–7 Shoulder arthroscopy and debridement is a commonly used initial surgical technique in the approach to treating patients with early glenohumeral degeneration, and several authors have demonstrated its potential for decreasing pain, improving function, and potentially delaying the need for eventual arthroplasty.8–15 These debridement and arthroscopic procedures often include a combination of debridement, chondroplasty, synovectomy, capsular release, and subacromial decompression (SAD). However, it is important to keep in mind that the goal of arthroscopy at this stage is not to cure the underlying disease process (arthritis) but rather to provide symptomatic improvement and maintenance of function for as long as possible. • Decreased ROM—specific documentation with preoperative ROM is essential • Sensation of crepitus, clicking, catching, or locking – Note: Some patients may have painless crepitus, and although this may signal articular cartilage disease, this is likely not the source of the patient’s symptoms (incidental finding). • Limited ROM compared with normal shoulder – Decreased forward flexion in patients with large inferior humeral head bone spur – Decreased external rotation in patients with flattened humeral head – Especially if a component of bursitis is present – Evaluation for tenderness over the LHB – Evaluation for tenderness over the acromioclavicular (AC) joint • Provocative testing such as LHB tension signs • Normal strength, though examination can be limited by pain • MRI (without contrast) can show the following: – Status of articular cartilage and subchondral bone – Soft-tissue pathologies (labrum, rotator cuff, biceps tendon)

Arthroscopic Management of Glenohumeral Arthritis

Preoperative Considerations

Physical Examination

Imaging

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Arthroscopic Management of Glenohumeral Arthritis