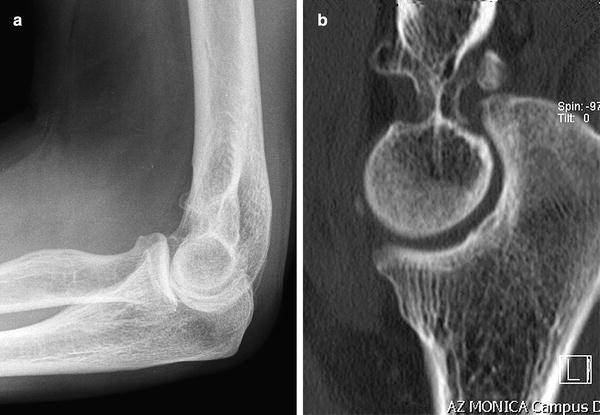

Fig. 31.1

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of a right elbow showing signs of advanced stage osteoarthritis. Note the joint symmetrical joint space narrowing, as well as ulnohumeral and radiohumeral osteophytes and obliteration of the anterior and posterior fossae. (Courtesy of MoRe Foundation)

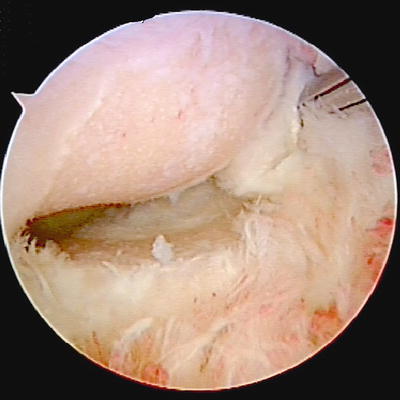

Fig. 31.2

The exact location of impinging osteophytes gets clear when analyzing CT images. Large osteophytes are present on the coronoid tip and coronoid fossa. These are likely to block flexion. The olecranon fossa has been filled by another large osteophyte and a large loose body is present in the posterior compartment. There is a smaller corresponding osteophyte at the tip of the olecranon. (Courtesy of MoRe Foundation)

Fig. 31.3

(a) Lateral radiograph of a left elbow showing mild osteoarthritic changes. (b) CT scan of the same elbow showing signs of advanced osteoarthritic disease with loose bodies and thickening of the olecranon fossa membrane. (Courtesy of MoRe Foundation)

Fig. 31.4

Three-dimensional reconstructions of native CT images are particularly helpful in localizing loose bodies, such as here in the radiohumeral gutter. (Courtesy of MoRe Foundation)

Ultrasound scans, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Technetium bone scans are usually not indicated, unless in cases where inflammation of the joint and/or discrete cartilage disruption or ligamentous injury are suspected.

Electromyography (EMG) is indicated when ulnar nerve symptoms are present. If the EMG is positive, an ulnar nerve release should be performed at the time of the arthroscopic procedure. If the preoperative arc of motion is less than 90° an ulnar nerve release should be contemplated, even when the EMG is negative.

Indications for Arthroscopic Surgery

The most common indications for surgery are pain and elbow stiffness, locking, or recurrent synovitis. Conservative measures such as physiotherapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and intra-articular corticosteroid injections are the first line of treatment, together with the pharmacological treatment of inflammatory disease, but if these fail surgery may become an option. Pro’s and cons as well as potential complications of all surgical options should be discussed with the patient. Arthroscopic and open debridement, the possibility of a total elbow arthroplasty and even arthrodesis should are discussed, depending on the severity of the symptoms and progression of the arthritis, so that the patient can make an informed decision. Arthroscopic arthroplasty is my preferred choice for the surgical management of elbow osteoarthritis.

ContraIndications for Arthroscopic Surgery

Besides general contraindications for surgery, such as poor health or significant comorbidities, there are no specific absolute contraindications to use an arthroscopic technique in the treatment of elbow arthritis. There are however several relative contraindications mostly relating to the safety of the procedure. These depend greatly on the experience of the surgeon and may include multiple prior surgeries and scars, retained hardware, previous ulnar nerve surgery, severe stiffness or instability, heterotopic ossification etc. It is important for the surgeon to know their limits as arthroscopic osteocapsular arthroplasty is technically demanding and becomes increasingly difficult if any of the previously mentioned cofactors are present.

In cases of severe bone loss or instability, arthroscopy is not likely to significantly improve the patient’s symptoms and an arthroscopic technique will not be indicated [7]. If the surgeon thinks the risk of complications or the potential gain from the arthroscopic technique are unacceptable, an open procedure or an intra-operative conversion to an open procedure should be possible and this should preoperatively be discussed with the patient.

Arthroscopic Technique

The elbow is examined thoroughly, once general anesthesia has been administered. The elbow is taken through the arc of motion and range, end-feeling (hard or soft), crepitus, or mechanical blocking are tested. Varus-valgus and rotator stability are tested as well. The patient is then positioned in lateral decubitus, with the arm over an armrest. Prone and supine positions are also possible, depending on the surgeon’s preference. The arm is exsanguinated and a tourniquet is used. The ulnar nerve is palpated and marked with a sterile skin marker. If a mini-open ulnar nerve release is indicated, it can be done at this moment. Other landmarks, such as the olecranon, epicondyles, and radial head can be marked as well. The elbow capsule is distended with approximately 25 ml of saline. The volume of the capsule can be significantly decreased in severe OA with capsular retraction.

It depends on the surgeon’s preference whether the anterior or posterior compartment is treated first. Some prefer to start the arthroscopy at the posterior compartment because it is often difficult to get a good view of the posterior structures. A posterior synovectomie and removal of fibrosis and intra-articular adhesions can be quite laborious and becomes more difficult once the soft tissues are swollen. Others prefer to start at the anterior comportment as neurovascular structures are particularly at risk anteriorly. Swelling and edema are limited at the beginning but are often pronounced at the end of the procedure.

Anterior Compartment

The anteromedial portal is made 2 cm proximal and 1 cm anterior to the medial epicondyl [8, 9]. The skin is incised only in order to protect the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. If a mini-open ulnar nerve release was performed, the portal can be included in this skin incision. The fascia anterior to the intermuscular septum is pierced with a blunt trocar. The humerus is posterior to the trocar at his point. In patients with OA it is very important to keep the trocar in contact with the humerus and directed at the radial head, as anterior osteophytes may deflect the trocar anteriorly in the direction of the radial nerve. The capsule is pierced and a standard 4.5 mm scope is inserted. The radial head is brought into view (Fig. 31.5). The position of the scope can be confirmed by rotating the forearm. The anterior compartment is inspected in a standard fashion, starting from the radial head and radiocapitellar joint. The scope is directed medially to visualize the coronoid process, coronoid fossa, and radial fossa on the humerus. The elbow can be flexed to improve the view.

Fig. 31.5

Arthroscopic view of the anterior compartment of the elbow, showing loss of cartilage from the radial head (bottom) and capitellum (top) and accompanying synovitis. (Courtesy of MoRe Foundation)

The position of the lateral portal is determined with a needle. The radial head is palpated and the needle is inserted into the joint, anterior to the radial head. The tip of the needle is directed towards the coronoid process, to make sure further instruments will be able to reach. The position of the lateral portal is crucial. If the portal is placed too posteriorly instruments it will not be possible to remove coronoid osteophytes (Fig. 31.6). The radial nerve will be at risk if the portal is placed too anteriorly [10].

Fig. 31.6

The position of the anterolateral portal is confirmed with a needle directed at the tip of the arthritic coronoid process. (Courtesy of MoRe Foundation)

A more proximal position (proximal anterolateral portal) will decrease the risk, when compared to a distal portal (anterolateral portal), but may again decrease the ability to work on the medial side of the elbow. An excellent 3D knowledge of the elbow’s anatomy is necessary in order to avoid injury to the important anterior structures.

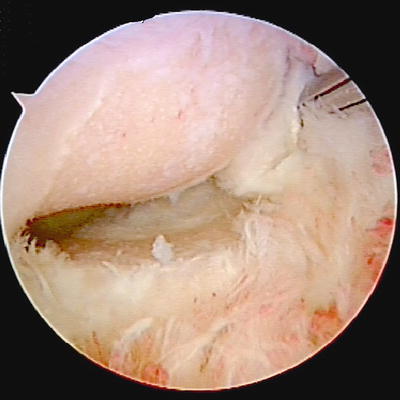

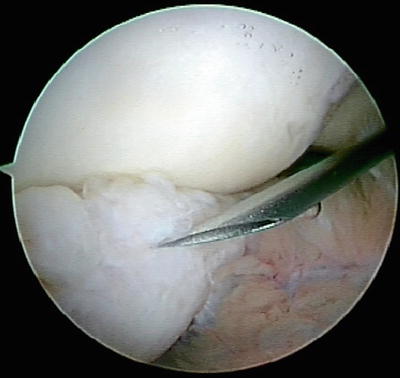

A synovectomie is performed with a shaver or radiofrequency (RF) probe and intra-articular adhesions are removed. In severe cases this step is necessary before the medial side of the elbow can be visualized. Care should be taken not to cut the capsule at this point, as this will increase swelling in the surrounding soft tissues, complicating the rest of the procedure. It should be noted that the capsule in patients with RA is often not thickened and is often relatively loose. It is imperative that the tip of the shaver is always in direct view and suction is not used when the shaver is active. The loose capsule in patients with RA can easily be sucked into the shaver and could be cut accidentally. This will of course increase the risk of neurovascular complications. Coronoid osteophytes are removed with a burr or a 5 mm osteotome (Fig. 31.7). Osteophytes blocking the coronoid and/or radial fossae are removed with a burr (Fig. 31.8). The elbow is moved to full flexion in order to check for further impingement. The radial head can be resected with a burr. Resection starts on the anterolateral quadrant of the head and further resection is done by rotating the forearm, while the burr is placed on the radial head. If it is not possible to resect the entire radial head, this can quite easily be finished from the soft spot portal with the scope in radial gutter.

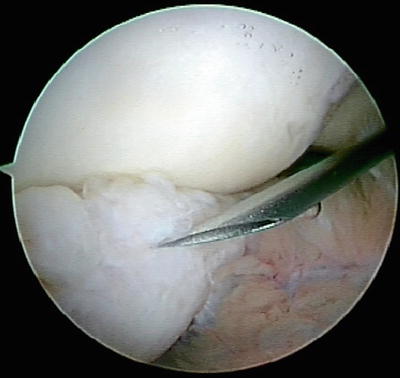

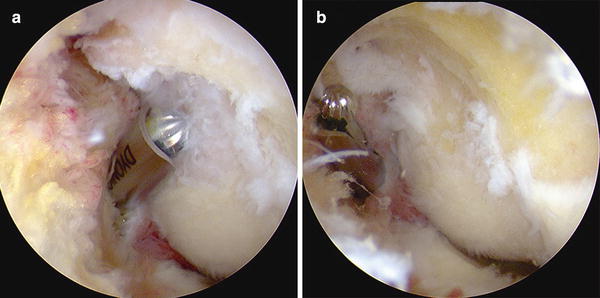

Fig. 31.7

(a) Osteophytes at the tip of the coronoid process can be removed with a burr or (b) an osteotome. (Courtesy of MoRe Foundation)

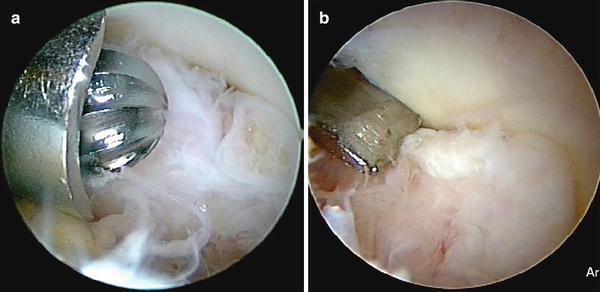

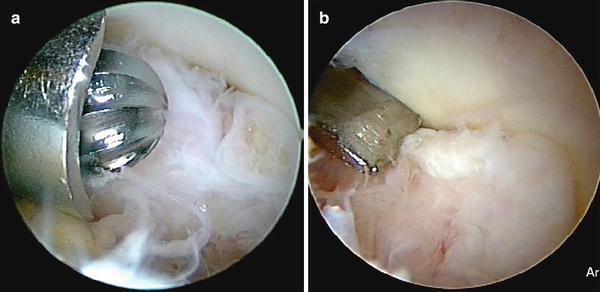

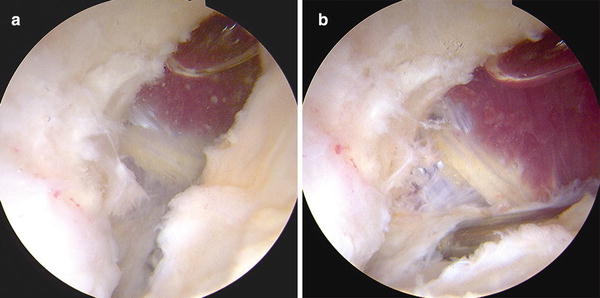

Fig. 31.8

(a) The burr is directed at a large osteophyte extending from the radial into the coronoid fossa. (b) the osteophyte is removed, so there is no longer a bony block to flexion. (Courtesy of MoRe Foundation)

A capsulectomy is performed at the end of the bony procedure. This step is not necessary if range of motion is normal was full preoperatively. Typically the scope is switched to the lateral portal and capsule is cut, from medial to lateral, with a duckbill. Alternatively the capsule can be cut from lateral to medial. The remainder of the capsule is then removed with a shaver. Particularly at this point, the radial nerve is at risk and care should be taken to protect the nerve at all times. The nerve is situated slightly medial to the anterior center of the radial head, directly against the capsule. The median nerve and brachial artery are somewhat protected by the brachialis muscle that lies between the nerve and the capsule [11].

It has not conclusively been proven that a complete capsulectomy offers a clear advantage over a simple release and some surgeons therefore prefer to perform a capsulotomy. This is technically less challenging and it may decrease the risk of neurologic injury. A capsulotomie is performed with the shaver on the humeral bone. The shaver is advanced from distal to proximal and the capsule is stripped from the bone. A blunt instrument can be used to further strip the capsule, until muscular fibers become visible and the capsule is fully detached from the bone (Fig. 31.9).

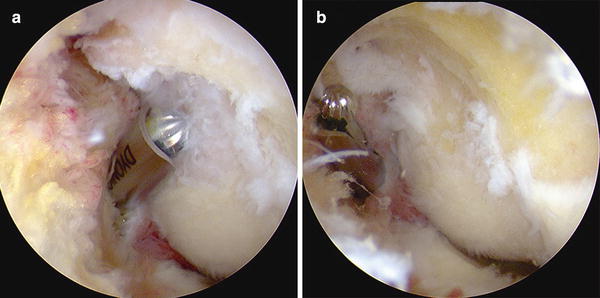

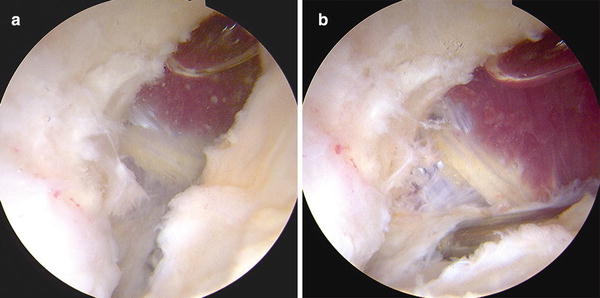

Fig. 31.9

(a) Humerus (left) and capsule (right) are separated with a shaver or a blunt instrument. (b) Once the capsulotomy is completed the remaining capsule can be removed with a shaver, but this is not always indicated and increases the risk of neurovascular complications. (Courtesy of MoRe Foundation)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree