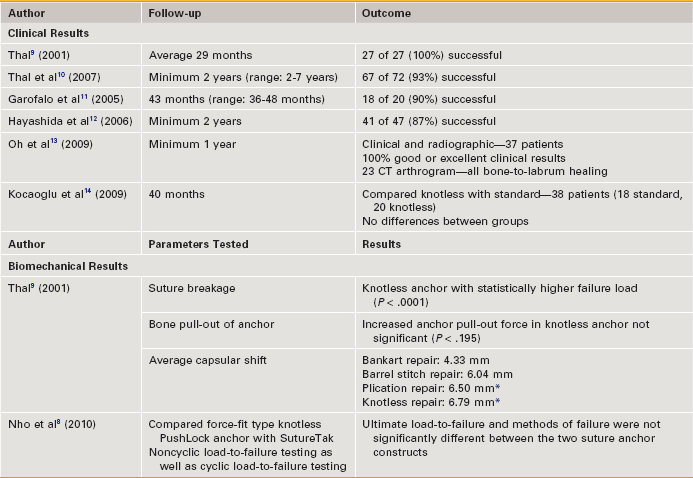

Chapter 5 Of the numerous surgical techniques introduced for performance of successful arthroscopic Bankart repair, fixation of the avulsed labrum with suture anchors has most consistently shown results comparable with those of open repair.1,2 This has often been attributed to the ability of suture anchors to achieve an anatomically reduced labrum and capsule while also providing a more secure construct when compared with other techniques such as bioabsorbable tacks. Traditional suture anchors, however, require proficiency with technically demanding knot designs and techniques, which are time-consuming and provide the surgeon little room for error. Furthermore, the completed knot may be bulky, and this has been reported to pose a threat to the glenohumeral cartilage via knot abrasion.3 In an attempt to simplify suture anchor placement, in 2001 Thal introduced the Mitek Knotless Suture Anchor (Mitek, Norwood, MA) and presented its use in the repair of Bankart lesions.4 The proposed advantages of this suture anchor were faster anchor placement and use, elimination of the arthroscopic knot as a source of failure, technical ease, and superior capsular shift compared with traditional anchors. Since its development, a number of other knotless anchors have been developed that offer the surgeon different options with regard to size, material, and method of fixation. In this chapter we discuss the functional characteristics of knotless anchors, the results of studies that have used such anchors for traumatic Bankart repair (Table 5-1), and the risks and benefits of use of such anchors versus traditional designs. TABLE 5-1 Results of Knotless Suture Anchor Fixation in Shoulder Instability *Statistically significant increase in capsular shift versus Bankart repair with standard suture anchors. Since introduction of the Mitek Knotless Suture Anchor, many anchor designs have been introduced that differ in material, method of fixation, and technique of application. Knotless anchors have been demonstrated to similarly restore labral height when compared with traditional suture anchors,5 but fundamental to their clinical performance is how the anchors will resist displacement once placed, because displacement of the anchor will result in displacement of the labrum and captured tissue from its appropriate position on the glenoid.6 Broadly, knotless anchors can be grouped based on their method of fixation into bone as either form-fit or force-fit. Form-fit anchors function by changing their original shape once deployed in such a way that they become wedged within the bone. The original Knotless Suture Anchor is an example of this, where nitinol arcs spread after insertion to increase resistance to pull-out. Force-fit anchors rely on the friction of the anchor-to-bone interface created by the anchor’s design to resist pull-out; screw-type anchors are an example of this. Initial biomechanical testing of the Mitek Knotless Anchor was done by Thal, who compared maximal pull-out strength of the Knotless Anchor with that of the Mitek GII anchor, on which its design was based.7 Results from these studies were encouraging—failure by suture breakage occurred at considerably higher loads in the Knotless Anchor group (55.6 pounds vs. 24.3 pounds with use of No. 1 Ethibond), and there was no significant difference in bone pull-out strength. As other designs have been introduced they have also undergone biomechanical and in vitro testing. Nho and colleagues compared the force-fit type knotless PushLock anchor with the SutureTak anchor (both from Arthrex, Naples, FL) with regard to both noncyclic load-to-failure testing and cyclic load-to-failure testing with use of simple, horizontal mattress, and double-loaded simple stitch patterns.8 This anchor has the proposed advantage of making final tissue tension independent of anchor depth, which would allow the anchor to be wedged more consistently in subchondral bone. Ultimate load-to-failure and methods of failure were not significantly different between the two suture anchor constructs. Overall, knotless suture anchors have provided good results in both clinical and biomechanical studies.

Arthroscopic Instability Repair with Knotless Suture Anchors

Knotless Anchor Design and Biomechanical Studies

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine