CHAPTER 9 Arthroscopic Evaluation and Diagnosis of the Patellofemoral Joint

In this chapter, we will focus on the following:

Specific pathologies (radiologic assessment, arthroscopic findings)—patellofemoral pain, chondromalacia, osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), instability, patellar maltracking

Specific pathologies (radiologic assessment, arthroscopic findings)—patellofemoral pain, chondromalacia, osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), instability, patellar maltrackingPATIENT EVALUATION

History and Physical Examination

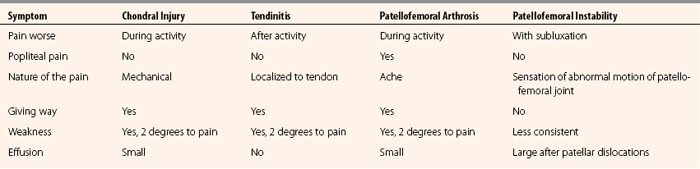

Differentiating acute from chronic problems, the quality of the patient’s pain, and what makes it better and worse all help the clinician make the diagnosis. Table 9-1 presents the major subjective differences when taking a history of a patient’s problem with patellofemoral complaints.

The physical examination should be performed with the goal of systematically evaluating the entire lower extremity. Patellofemoral problems can stem from malalignment secondary to femoral anteversion, genu recurvatum, genu varum, genu valgum, tibial torsion, pes planus, or ligamentous laxity. The extensor mechanism should be evaluated, as well as patellar position, mobility, and tracking.

Next, the examiner should evaluate the joints above and below the knee (hip along with the foot and ankle). It is easy to focus on the knee and patellofemoral joint. Examine all aspects of the knee prior to focusing on the suspected patellofemoral problem (Table 9-2).

TABLE 9-2 Physical Examination of the Patellofemoral Joint

| Parameter | Features | Abnormal Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Observation | Alignment | Varus, valgus, patella (alta, baja, or squinting), decreased foot progression angle, pes planus (increased forefoot pronation) |

| Palpation | Knee joint | Effusion, tenderness, crepitus, pain with patellar compression on ROM |

| Range of motion (ROM) | Passive and active | Amount of ROM, limited end points, extensor lag |

Lateral → translation of > 50% of patella width is abnormal; if no hard end point, MPFL (53% of lateral stability) is out | ||

ASIS, anterosuperior iliac spine.

Anatomy

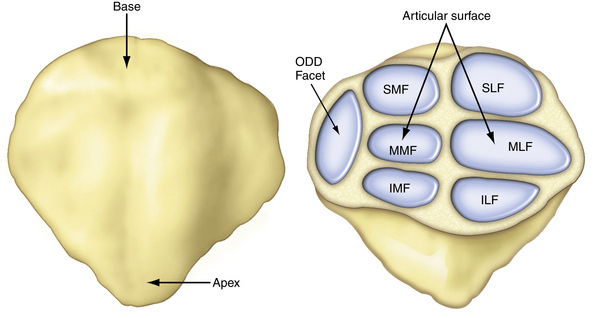

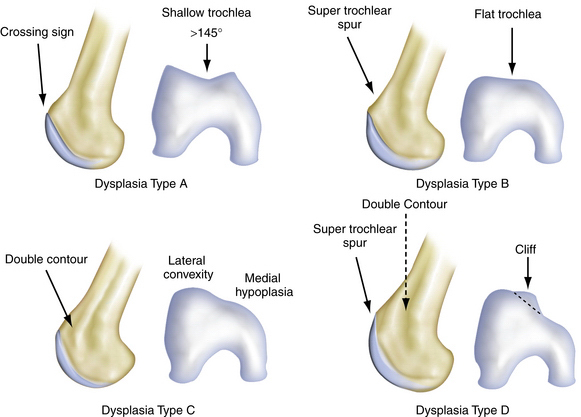

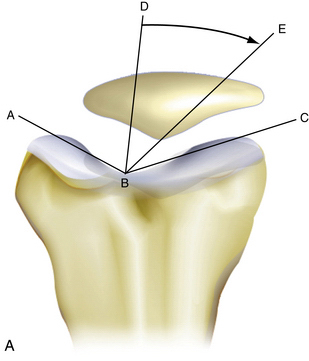

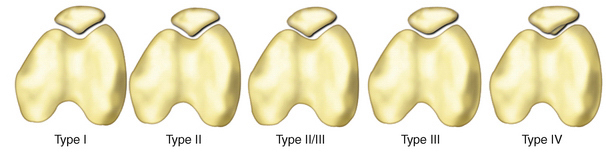

The anatomical landmarks of the patellofemoral joint are the seven facets of the posterior patella (Fig. 9-1). The medial and lateral facets are each divided into roughly equal thirds and the seventh facet is the odd facet located on the extreme medial border of the patella. On the trochlear side, the patella articulates with the femoral joint surface on the medial and lateral sides of the trochlear groove. The contact area pressures vary in location and load depending on the level of flexion. The patellofemoral contact, load, and tracking are also affected by anatomical variants, as described by Wiberg and Baumgartl (Fig. 9-2). Also, anatomic abnormalities such as patella baja, patella alta, trochlear dysplasia, rotational alignment of the femur and tibia, foot alignment, tight lateral retinaculum, and vastus medialis strength also play a role in the tracking and articulating pressures and contact locations (Fig. 9-3).

FIGURE 9-2 Anatomic variants of the patella as described by Wiberg and Baumgartl.23 I. Equal medial and lateral facets which are both slightly concave (normal anatomy), II. Smaller medial than lateral facet, medial facet is flat or slightly convex, III. Very small medial facet which is convex, IV. Without a medial ridge or medial facet.

FIGURE 9-3 Anatomy of the medial aspect of the knee. The MPFL provides 53% of the restraint to lateral displacement of the patella. The patellomeniscal ligament and medial retinacular fibers are responsible for 22% of patellar restraint.

Anatomic variations responsible for patellofemoral problems vary, depending on the pathology. Excessive femoral anteversion, tibial torsion, patella alta, and shallow trochlea are all causes of patellar instability, and pain caused by instability (Fig. 9-4).

Diagnostic Imaging

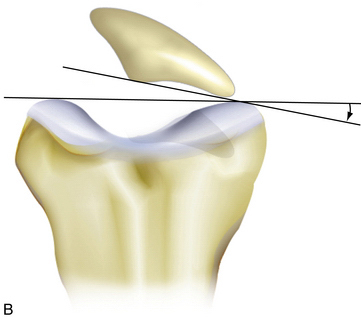

When the patella does not engage in the trochlea by 15 to 20 degrees of knee flexion, patella alta may be present. Patella alta may be radiographically assessed in many ways. Laurin and Merchant axial radiographs are obtained with the knee flexed 20 and 40 degrees, respectively (Fig. 9-5). These assess patellar tilt, but one tangential radiograph obtained at 30 degrees of flexion is sufficient in most cases. The x-ray beam is projected caudad at an angle of 30 degrees from the plane of the femur. A line is drawn along the lateral facet of the patella, and a second line is drawn between the condyles of the trochlea anteriorly. Normally, the angle between these two lines will be open laterally. However, if the lines are parallel or the angle opens medially, the patella is probably tilted.

Teitge and colleagues1 have described a radiographic technique that can be helpful for diagnosing patellar instability. They obtained bilateral axial radiographs of the patellofemoral joints in anatomic position, with constant medial and lateral force applied to the patellae with an instrumented device, and then axial radiography was repeated. It was found that a 4-mm increase in medial or lateral patellar excursion compared with the patellar excursion on the asymptomatic knee correlated with patellar instability. Stress radiographs are helpful in identifying patients with congruity of the articular surfaces whose knees may subluxate or dislocate because of deficient ligamentous structures. Patients who are unable to relax the extensor mechanism because of pain or who have bilateral symptoms are not candidates for stress radiography.

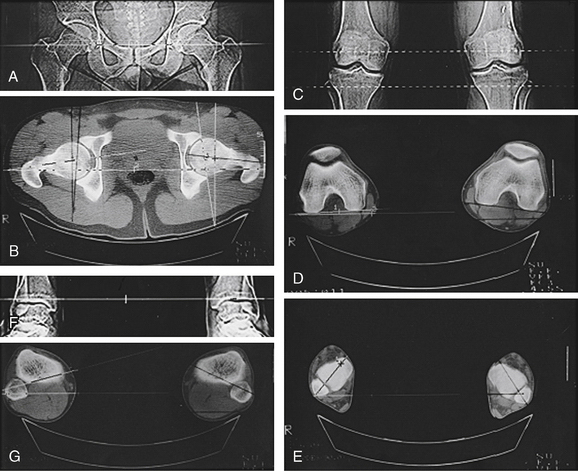

Once x-rays have been evaluated, limb alignment may be further evaluated for rotational malalignment with an overlay alignment CT scan to measure femoral anteversion and tibial torsion. CT has been shown to be more sensitive than axial radiography in delineating patellar malalignment2; it allows axial cuts of the patellofemoral articulation at angles less than 20 degrees of knee flexion, which enhances the detection of subluxation as the patella loses the stabilizing function of the lateral femoral condyle. Another role for CT is in identifying lateralization of the tibial tubercle, as measured by the distance between the tibial tubercle and the trochlear sulcus (Fig. 9-6). An axial CT image demonstrating the femoral trochlear groove is superimposed on an axial image of the tibial tubercle. A line is drawn on this superimposed image between the posterior margins of the femoral condyles. Two lines are drawn perpendicular to this line, one bisecting the femoral trochlear groove and the other bisecting the anterior tibial tuberosity. The distance between these two lines determines the extent of lateralization of the tibial tubercle. Values greater than 9 mm have been shown to identify patients with patellofemoral malalignment, with a specificity of 95% and a sensitivity of 85%.3