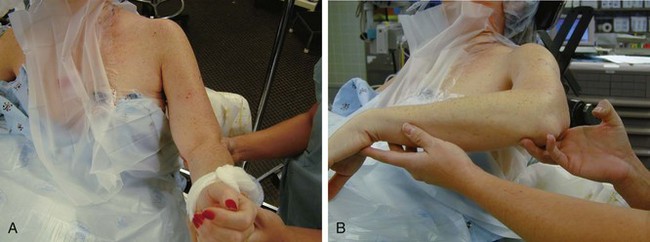

Chapter 30 The diagnosis of shoulder stiffness, also termed frozen shoulder or adhesive capsulitis, is one of exclusion. It is a clinical syndrome characterized by painful restricted passive and active range of motion. It is associated with night pain and pain with activities.1–5 This clinical entity has been difficult to classify and follows an unpredictable clinical course.1,3,6,7 Etiologic factors in the pathophysiology of the disease include idiopathic causes, posttraumatic conditions, diabetes, and postsurgical factors; the condition can arise even as a consequence of prolonged impingement syndrome.4,5,8–11 It appears that susceptible shoulders respond to an insult in a common pathway of expression. This is a glenohumeral synovitis. If this process continues unabated, the capsule will become thickened and disorganized in its collagen structure and actually become contracted.12,13 The time course of the process and recovery is unpredictable. The true cause, diagnostic criteria, pathophysiology, treatment methods, and natural history of this condition are under debate and investigation.1,4–8,14–16 There are patients who do not respond to time, proper therapy, injections, or anti-inflammatory medications and who are profoundly affected by the shoulder stiffness. These patients can be offered an arthroscopic capsular release. Plain radiographs will evaluate conditions such as arthritis of the glenohumeral joint, calcific tendonitis, and subacromial impingement. A true anteroposterior (AP) view of the glenohumeral joint, an axillary view, and an outlet view should be performed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can evaluate for rotator cuff pathology, but in a true adhesive capsulitis picture, MRI will exclude other pathology. Bone scan, computed tomography (CT), and electromyography are rarely necessary for the evaluation of frozen shoulder. Arthrography with limited joint volume was at one time felt to be a gold standard–type test,3 but it is not necessary for the diagnosis of shoulder stiffness if a proper history is obtained and a proper physical examination is performed. Another diagnostic test can be physical therapy. A patient who does not respond to or who actually gets worse with a therapy program designed specifically for shoulder stiffness can be a candidate for arthroscopic capsular release. Conservative treatment should always be attempted. As mentioned previously, injections can relieve pain and facilitate therapy. The pathophysiology is that of glenohumeral inflammation. Corticosteroid injections into the glenohumeral joint can decrease the inflammatory response, relieve pain, and allow better motion. An oral steroid medication can also be used. Gentle range of motion and stretching are instituted. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used after or in conjunction with steroids. If the pain is relieved, most patients can accept the limitations of motion.6,7 This allows more time to restore motion and function. Some patients do not respond to conservative management. A recalcitrant frozen shoulder is one that has had symptoms for over 4 months and has not responded to a surgeon-directed therapy program directed toward the diagnosis of shoulder stiffness. This program should be given at least 6 weeks to show progress. If patients still have sleep disturbance, pain, and limitation of motion that affects their occupation, recreation, and sleep, then it is time to consider an arthroscopic capsular release.4,17,18 The cause of the stiffness has been found to not have a significant effect on the outcome of arthroscopic capsular release; thus the procedure is equally effective across causes.4 The patient is placed in the beach chair position with a small towel roll under the medial border of the scapula. The landmarks of the scapular spine, acromion, and coracoid are marked out after standard preparation and draping. An assessment of motion is made with the patient under anesthesia (Fig. 30-1). No manipulation is performed at this time. It would create bleeding within the glenohumeral joint and make for a more difficult procedure.

Arthroscopic Capsular Release for the Treatment of Stiff Shoulder Pathology

Preoperative Considerations

Imaging

Conservative Treatment

Indications for Surgical Intervention

Surgical Technique

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Arthroscopic Capsular Release for the Treatment of Stiff Shoulder Pathology