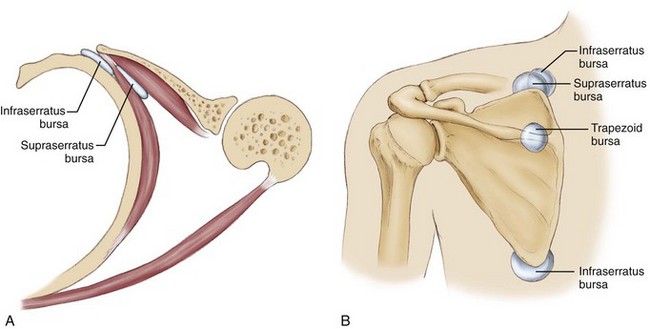

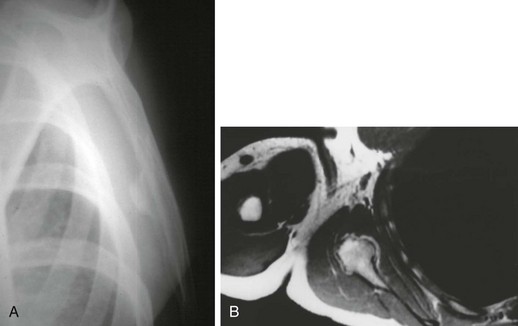

Chapter 31 Knowledge about the interplay of structures and biomechanics surrounding the scapula and its role in shoulder motion is evolving steadily. The result is that our understanding of shoulder disease is also increasing. It is becoming clear that processes affecting the scapula in turn greatly influence the function of the shoulder.1 Conditions of the scapulothoracic articulation can be broadly divided into four main disease processes: bursitis, crepitus, dyskinesis, and winging. Each of these is a unique entity, but they are often seen in combination. Scapulothoracic bursitis manifests as posterior shoulder pain with range of motion. The patient can often localize the pain under the scapula. Two major bursae are consistently identified: the infraserratus bursa between the serratus and the chest wall and the supraserratus bursa between the subscapularis and the serratus (Fig. 31-1). In addition, four minor adventitial bursae have been described.2 Clinically significant bursitis tends to affect two areas most commonly: the superior medial angle and the inferior angle. The bursae at these locations are minor adventitious bursae that may become apparent only when they are inflamed. Through a process that is similar to subacromial bursitis, repetitive motion of the scapula over the rib cage causes inflammation and edema in the bursae. As with other types of bursitis, this process can be initially treated with rehabilitation and judicious corticosteroid injections.3 This is often sufficient to quiet the process and relieve the patient’s symptoms. On occasion the bursitis is refractory to medical management, and surgical intervention in the form of a bursectomy is required. Winging of the scapula is a finding that may result from many causes. In athletes, winging is typically seen as an isolated palsy of the serratus caused by a long thoracic nerve neurapraxic injury. Winging may also be seen with profound scapular bursitis or may manifest as part of scapular dyskinesis. Scapular dyskinesis is defined as abnormal motion of the scapula characterized by medial border or inferior angle prominence, early excessive scapular elevation and shrugging, or rapid downward rotation during lowering of the arm.1 A static abnormality of scapular position, called the SICK scapula (scapular malposition, inferior medial border prominence, coracoid pain and malposition, and dyskinesis of scapular movement), probably represents a more severe state of this condition.4 Whereas dyskinesis is likely to be the most common finding in the athlete with shoulder pain, it is best treated with appropriate rehabilitation and will not be explored in detail in this chapter. Winging caused by bursitis typically resolves with treatment of the bursitis. Winging caused by long thoracic nerve injury resolves spontaneously in most athletes; when it persists, surgical intervention can be considered. The physical examination for scapulothoracic disorders requires the physician to stand behind the patient, who is disrobed or wearing a sports bra. The scapular position at rest should be noted. A scapula that is depressed, anteriorly tilted, and internally rotated suggests a SICK scapula and typically has tenderness at the pectoralis minor insertion on the coracoid.4 The patient is asked to elevate and then lower the arms while the physician looks for dyskinesis. Crepitus can be heard, and the location of crepitus (superomedial angle or inferior angle) frequently can be determined by careful palpation. Provocative testing to elicit winging can be performed by having the patient push off from the wall or elevate the arms against resistance (Fig. 31-2). Radiographs are helpful to find subscapular bone prominences (Fig. 31-3) and include the following views: Most scapulothoracic problems in athletes are not treated surgically. Rehabilitation focused on pectoralis minor stretching, serratus and lower trapezius strengthening, posterior capsule stretching, and core strengthening will treat the SICK scapula and scapular dyskinesis.4 Patients with scapular bursitis and milder forms of crepitus will often respond to similar rehabilitation and the judicious use of corticosteroid injections. With the mixing of steroid and local anesthetic, injections can be therapeutic and diagnostic, perhaps giving an indication of potential postsurgical results. Athletes with long thoracic nerve injury can be monitored for many months with serial electromyography as the nerve typically recovers spontaneously, occasionally taking up to 2 years. Bracing may help with symptom relief while the nerve recovers. When nonoperative approaches fail, surgery may be considered for these conditions.

Arthroscopic and Open Management of Scapulothoracic Disorders

Preoperative Considerations

Physical Examination

Imaging

Indications and Contraindications

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine