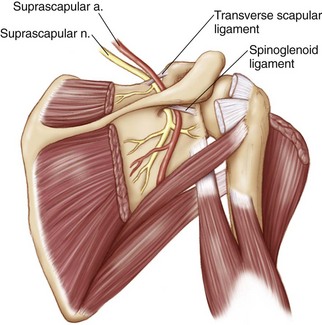

Chapter 27 Suprascapular neuropathy is thought to result from compression or tethering of the nerve as it courses under the suprascapular notch (Fig. 27-1). Compression of the suprascapular nerve (SSN) can result from a variety of causes that narrow the notch: supraglenoid cysts, fracture of the scapular notch with resultant callus formation,1 an enlarged or thickened transverse scapular ligament, hardware from prior surgical interventions, or any space-occupying lesion in the region of the notch.1–4 Tethering of the nerve results from more dynamic mechanisms: retraction as the result of massive rotator cuff tears, repetitive traction injuries in overhead athletes such as volleyball players and pitchers, and traumatic stretch injuries associated with glenohumeral dislocations or proximal humerus fractures.5–10 Injuries to the nerve can result in inflammation and swelling of the nerve, causing further compression at the suprascapular notch. The diagnosis of suprascapular neuropathy can be challenging, as the presenting symptoms are generally nonspecific. Patients most often describe a deep or dull aching pain in the posterolateral aspect of the dominant shoulder or directly above the supraspinatus fossa.11 Patients may also report weakness, particularly in abduction and external rotation. Symptoms may start immediately after a traumatic injury or may develop slowly over time.11,12 Chronic conditions may be more common in individuals with substantial overhead demands, whether athletic or work related. On physical examination it is important to completely visualize the shoulders from posteriorly to detect associated atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus fossa. Isolated infraspinatus fossa atrophy suggests that the nerve injury is at the level of the spinoglenoid notch. Weakness in abduction and external rotation may also be evident. Maneuvers attempting to place the SSN under tension may reproduce the patient’s symptoms. Lafosse and colleagues suggest a stretch test that laterally rotates the head away from the involved shoulder while also retracting the shoulder posteriorly.13 Cross-body adduction and internal rotation may also reproduce pain by tensioning the spinoglenoid ligament and further tethering the nerve.14 Imaging is used primarily to assess for the commonly associated conditions mentioned previously, but also to evaluate for space-occupying lesions near the suprascapular or spinoglenoid notch. The degree of atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles can also be determined with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Additional diagnostic studies include electromyography and nerve conduction velocity tests.9,15 The reliability of these tests is unclear. If the surgeon has a high degree of suspicion for SSN pathology, a fluoroscopically guided injection of anesthetic and cortisone into the suprascapular notch can be performed. • Patients with a space-occupying lesion at the suprascapular notch with pain and weakness • Patients with electromyographic evidence of suprascapular neuropathy • Patients with a negative electromyogram (EMG) who experience substantial relief of their symptoms with fluoroscopically guided injection of anesthetic and cortisone • Patients with massive rotator cuff tears with either a positive EMG or relief of their symptoms with fluoroscopically guided injection of anesthetic and cortisone • Patients with cervical radiculopathy (address underlying spine pathology first) • Patients with brachial plexitis (follow conservatively until resolution of general inflammation) • Patients who do not experience any relief of symptoms after fluoroscopically guided injection of anesthetic and cortisone, in the absence of a space-occupying lesion

Arthroscopic and Open Decompression of the Suprascapular Nerve

Preoperative Considerations

Indications

Contraindications

Arthroscopic and Open Decompression of the Suprascapular Nerve