Lisfranc Arthrodesis

Keywords

• Lisfranc • Tarsometatarsal • Arthrodesis • Fracture • Fusion

Anatomy

The tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint or Lisfranc joint comprises the articulation between the bases of the first, second, and third metatarsals with their respective cuneiforms and the bases of the fourth and fifth metatarsals with the distal aspect of the cuboid. The TMT joint complex is a plane-gliding type of synovial joint that is supported by a strong network of dorsal, plantar, and interosseous ligaments. The lateral tarsal artery of the dorsalis pedis provides blood supply. The deep peroneal, medial plantar, lateral plantar, and sural nerves provide nerve supply.1

The unique bony and ligamentous anatomy of the metatarsals, cuneiforms, and cuboid provide the architecture for the stable transverse and longitudinal arches of the foot. A cross section of the transverse arch reveals a structure similar to a Roman arch, which has inherent stability. A Roman, or centenary, arch has a central keystone that is bordered by voussoirs, or wedge-shaped bricks, that provide a locked structure. When examining the transverse arch of the foot, the second metatarsal and middle cuneiform joint act as the keystone and the wedge-shaped medial and lateral cuneiforms provide the struts that create a strong stable complex. The middle cuneiform is the smallest of the cuneiforms and is recessed approximately 8 mm relative to the medial cuneiform and 4 mm relative to the lateral cuneiform.2 This locks the second metatarsal within the complex, adding to the stability of the joint.

A complex network of dorsal, plantar, and interosseous ligaments provides additional stability to the TMT joint. The plantar ligaments are stronger than the dorsal ligaments, which accounts for a predisposition for dorsal dislocation with injury.3 The second metatarsal is anchored to the medial column by the strong Lisfranc ligament. The Lisfranc ligament is the strongest of the multiple ligaments within the complex measuring 1.0 cm in height and 0.5 cm in thickness.2,3

Mechanism of injury

Injuries to the TMT joint complex account for 0.2% of all fractures, with an incidence of 1 in 55,000 yearly.4,5 Injuries are usually indirect, caused by axial loading on a plantarflexed foot. These low-energy injuries tend to be missed because frank dislocation is not always present. Purely ligamentous injuries to the TMT joint complex are associated with longer recovery times and persistent symptoms at the area.6 Direct injury can result from a motor vehicle accident, fall, or crush injury. These types of injuries are higher energy and, if diagnosis is missed, can result in compartment syndrome because of the close proximity of the neurovascular bundle.

Classifications

Quenu and Kuss7 were the first to classify TMT injuries in 1909. Their classification divided injuries into homolateral, isolateral, and divergent. The classification described the direction of dislocation of the metatarsals with respect to the cuneiforms and cuboid.7 In 1982, Hardcastle and colleagues8 elaborated on the Quenu and Kuss classification, by dividing injuries into 3 categories: A, B, and C. Type A injuries were complete displacement of all metatarsals (total incongruity) in the sagittal or transverse plane. Type B injuries were partially incongruous, and type C injuries were divergent. In 1986, Myerson and colleagues9 further subdivided the Hardcastle classification. They described type B1 to be partially incongruous with medial dislocation with displacement of the first metatarsal in isolation or in combination with displacement of the lesser tarsus. Type B2 was partially incongruous with lateral dislocation with the first metatarsal unaffected. Type C1 was described as partially divergent with the first metatarsal displaced medially and a portion of the lateral complex displaced laterally in the sagittal and/or transverse planes. Type C2 was described as total divergent with the first metatarsal displace medially and the lateral complex displaced laterally.

Diagnosis/imaging

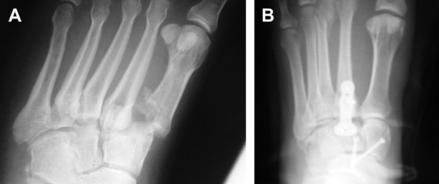

The diagnosis of a Lisfranc injury can be difficult. Often, a patient presents after an injury with midfoot swelling, ecchymosis, and sometimes frank dislocation of the medial and/or lateral column (Fig. 1). A subtle dislocation of the TMT joint or a purely ligamentous injury to the complex is more complicated to diagnose.

Myerson and colleagues9 described a pathognomonic sign called the fleck sign that represents an avulsion of the second metatarsal-middle cuneiform ligament. This sign is not always present when the TMT joint complex is injured but is a definite indicator of a diastasis when it is seen on radiographs. If no fleck sign is seen, radiographs should be inspected for displacement of more than 2 mm between the first and second metatarsal bases, which is indicates a Lisfranc injury.10

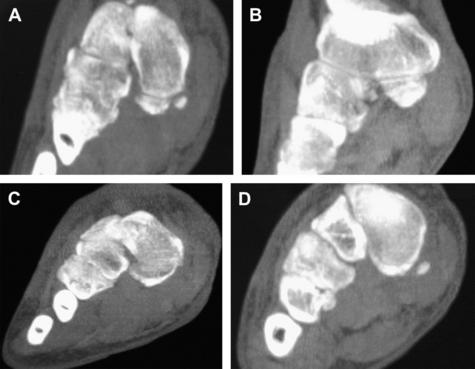

Advanced imaging is recommended when operative treatment is going to be performed or when a purely ligamentous Lisfranc injury is suspected. Computed tomography (CT) evaluation can aid in surgical planning and assessing the extent of articular involvement of any associated fracture. Three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction CT imaging is often performed at our facility to better visualize the disorder (see Fig. 1B–E). Stress radiographs are useful but difficult to perform because of patient discomfort. We routinely perform these during surgery. MR imaging is useful for subtle injuries to diagnose purely ligamentous injuries.

Open reduction internal fixation indications

Lisfranc injuries are rare, and most are unrecognized, misdiagnosed, or there is a delay in the diagnosis. They are severe injuries that, if untreated, have negative sequelae on the patient’s function and overall quality of life. Myerson and colleagues9 stated that there is no place for conservative treatment of fractures or fracture-dislocation of the Lisfranc joint. We strongly agree. Although most foot and ankle surgeons agree that surgical intervention is necessary for injuries of this complex joint structure, there is controversy about how to manage it. Some investigators advocate open reduction internal fixation (ORIF), whereas others recommend performing an arthrodesis. Most of the current literature supports ORIF of Lisfranc injuries as the primary treatment. The mainstay of surgical treatment of Lisfranc injuries, which all investigators agree on, is achieving a good anatomic reduction, which has been shown to be associated with a good functional outcome.10,11 This article discusses the controversies of surgical management of the Lisfranc joint in the literature and our indications for surgical management. Our indications for ORIF of the Lisfranc joint complex are as follows:

Myerson and Cerrato10 discussed the treatment of Lisfranc fractures10 in high-performance athletes. They concluded that primary arthrodesis is a difficult operation and the resulting stiffness may not be desirable compared with the outcome in a patient who recovers well from ORIF or closed reduction and internal fixation. Primary arthrodesis is not recommended for athletes, regardless of the potential for a rapid return to activity. They think that maintenance of motion in the medial column as well as the limited motion in the middle column is necessary to restore full function in these patients.10 Vertullo and Nunley13 also stated that treatment of subtle Lisfranc injuries with primary arthrodesis can be done, but is controversial in athletes. The risk of nonunion is difficult to accept, and return to professional sport after primary Lisfranc arthrodesis is rare.12,13 We agree with all the investigators that Lisfranc arthrodesis in an athlete should be reserved only if significant chondral injury is present at the time of open reduction. A semiprofessional wrestler sustained a Lisfranc fracture-dislocation and was treated with ORIF (Fig. 2). It has been 2 years since the ORIF and the patient has returned to his normal level of activity without any pain or limitations.

Fusion Indications

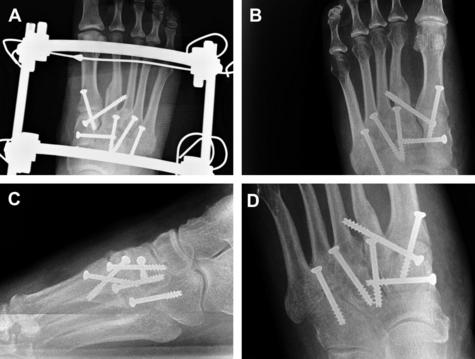

In 2006, Coetzee and Ly14 described their selective indications for a primary fusion of the Lisfranc joints. They performed primary fusions when major ligamentous disruptions and multidirectional instability of the Lisfranc joints, comminuted intra-articular fractures at the bases of the first or second metatarsal, and crush injuries of the midfoot with an intra-articular fracture-dislocation are present. Their contraindications for primary fusion are Lisfranc injuries in children with open physis, subtle Lisfranc injuries with minimal or no displacement, unidirectional Lisfranc instability, and unstable extra-articular fractures of the metatarsal bases with unknown amounts of ligamentous disruption.14 The investigators agree with Coetzee and Ly’s14 indications and contraindications for arthrodesis of the Lisfranc joint, but they only include the most common indications that are trauma related. Chronic pain and deformity can occur with ignored Lisfranc injuries (Fig. 3). In such cases, an arthrodesis is indicated (Fig. 4).

A controversy exists as to whether the Lisfranc joint complex should be fused primarily or reserved strictly for a salvage procedure. According to the literature, primary arthrodesis is not recommended for Lisfranc complex injuries.15,16 Instead, arthrodesis has been reserved as a salvage procedure after failed ORIF, for a delayed or missed diagnosis, and for severely comminuted intra-articular fractures of the TMT joints.14,16 However, in the more recent literature, a strong indication for primary arthrodesis of the TMT joints has been discussed. Granberry and colleagues17 recommended primary fusion in any unstable injury requiring open reduction because of the high incidence of these injuries that went on to arthrodesis. Sangeorzan and colleagues18 found a positive correlation between early arthrodesis following failed primary treatment with positive results. A primary arthrodesis potentially prevents a patient from developing a painful, deformed foot and decreases or prevents the need for further surgery and further disability. Henning and colleagues19 concluded that primary arthrodesis resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the number of follow-up surgeries performed compared with primary ORIF if hardware removal is routinely performed. Patients treated with primary arthrodesis for primarily ligamentous joint injuries function as well as those patients treated with primary ORIF.

Kuo and colleagues20 suggested that there is a subgroup of patients with a purely ligamentous Lisfranc injury who may better treated with primary fusion. They found that purely ligamentous Lisfranc injuries do not always heal following ORIF and that there was a tendency for this type of injury to result in osteoarthritis.14,20 In 2006, Coetzee and Ly14 published their results comparing ORIF and primary arthrodesis of the Lisfranc joint consisting of purely ligamentous injuries. They enrolled 41 patients with an isolated acute or subacute primary ligamentous Lisfranc joint injury in a prospective randomized study. Twenty patients were treated with ORIF and 21 with primary arthrodesis of the medial 2 or 3 rays. At 2 years after surgery, the mean American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) midfoot score was 68.6 in the ORIF group and 88 points in the arthrodesis group. Of the 20 patients in the ORIF group, 16 underwent a secondary surgery to remove prominent or painful hardware. Follow-up radiographs showed evidence of loss of correction, increasing deformity, and degenerative joint disease in 15 patients. Five of these patients in the ORIF group had persistent pain and developed osteoarthritis, and were eventually treated with arthrodesis. The patients in the arthrodesis group stated that their postoperative level of activity was 92% of their preinjury level compared with only 65% for the patients who had ORIF. Coetzee and Ly14 study concluded that primary stable arthrodesis of the Lisfranc joint complex has a better short-term and medium-term outcome than ORIF. Kuo and colleagues20 found that the mean AOFAS score for midfoot ORIF was 78.8 compared with the 57.1 found by Coetzee and Ly,14 but Coetzee and Ly’s14 mean AOFAS score for their arthrodesis group was higher at 86.9 points. They concluded that, in primarily ligamentous injuries, healing of the ligaments and capsules provided insufficient strength to maintain the initial reduction.14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree