Sorush Batmangelich

![]()

4: Application of Principles of Professional Education for Physicians

![]()

GOALS

Demonstrate knowledge and application of principles to the practice of professional education in the physician teaching and learning enterprise.

OBJECTIVES

1. Discuss the principles and practice of adult education in the context of physician professional development.

2. Describe Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)’s new accreditation system (NAS), milestones, competencies, clinical competency committee (CCC), clinical learning environment review (CLER), and residency review committee (RRC) roles.

3. Discuss/demonstrate effective techniques for enhancing didactic, clinical, case presentation, psychomotor, and bedside teaching skills.

4. Demonstrate/practice/role-play delivery of constructive feedback.

5. Examine various models of supervision.

6. Review the qualities and characteristics of mentorship.

The continuum of physician education embodies undergraduate medical education (4 years), graduate medical education (another 4 years), and continuing medical education/continuing professional development (up to 40+ years). Although the focus of this chapter and book is on professional development of faculty, residents, and fellows, as well as graduate medical education spanning residency and fellowship training and development, the application and practice of professional education principles applies to the entire spectrum of physician education.

Professional education has evolved into a complex system. Health care is transforming itself and undergoing reengineering of how to best address health care through interprofessional teams. Educating health care professionals should keep up with this transformation. Medical education is about patient-centered care that should exist within the realm of learner-centered education. The objectives for this chapter are to provide tools and strategies for professional development, as well as recommend practical and relevant applications and “how to” guides and tips to complement your clinician educator’s portfolio and armamentarium. You should be able to apply many of these skills immediately to enhance and improve your proficiency and techniques as educators. By the end of this chapter, we expect that you will improve your skills as educators and become sensitive to providing, recognizing, sensing, and seizing opportunities for teachable moments and learning moments. Teachable and learning moments are brief episodes characterized by intentional and/or unplanned signals and opportunities for bridging resident/fellow education gaps by the clinician educator.

Content areas covered include competencies, milestones, teaching and feedback, evaluation, supervision, and mentorship.

COMPETENCIES

The Oxford dictionary defines the noun competence as “the ability to do something successfully or efficiently.” The Merriam Webster dictionary defines competence as “an ability or skill” with synonyms such as capability, capableness, capacity, ability, and faculty. Competency is the composite of knowledge, skills, and attitudes/values to allow the individual to effectively perform in one’s practice setting and meet the profession’s standards. Knowledge, skills, and attitudes/values are the classical three-legged pillars of professional education that shape the judgments essential for interprofessional collaborative practice.

The continuum of physician education is driven by the six core competencies embedded in all residency and fellowship program requirements. These competencies are patient care/procedural skills, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice. Residency and fellowship programs focus on building and demonstrating proficiency in the six core competencies.

The core competencies are core values that constitute the basic foundation for physician development, defined not only by clinical skills but also, equally important, by the skills of the heart, values, and cultivating habits of lifetime practice that is immersed in self-assessment, inquiry, innovation, and discovery. Competence is defined as “the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individuals and communities being served”(1).

Physicians are trained to be clinicians and expected to be teachers. The six domains of competencies were articulated and adopted by the ACGME and the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) in the late 1990s and became the essential requirements of organized medicine and physician education across undergraduate, graduate, and continuing medical/professional education development.

Residents must learn and integrate the six competencies into their daily professional conduct. This cannot happen unless faculty members serve as role models for these competencies. You cannot teach competencies and quality care if you are not doing it.

These core competencies inform the culture of continuous improvement and accountability, and have become the common currency and expected standard measures and markers in improvement of quality, safety, and efficiency (triple aim) of the U.S. health care system. In addition to accrediting organizations, insurers, hospitals, and organizations representing quality, credentialing, and the federal government have embodied these core competency values.

The six core competencies, expectations of each competency, and content guide defining each competency is represented by Appendix 1.

ACGME’S NAS AND EDUCATIONAL MILESTONES

Beginning in 2009, the ACGME began to articulate and reorganize its accreditation system to the commonly known NAS, heralded by “milestones” and “levels” as fundamental underpinnings (2). The NAS transitions the ACGME’s accreditation system from a “process” orientation to that of “educational outcomes.” The NAS has two major objectives: (a) assessment of trainees to determine if the resident/fellow is competent and (b) accreditation of the residency/fellowship program. The milestones support a framework for the assessment of the development of the physician in key dimensions of the elements of physician competency in the given specialty. The milestones for each specialty have been crafted by a working group made up of members of the respective RRC, the ABMS certifying board, program directors, and residents.

The educational milestones are observable developmental steps, organized under the 6 competency areas, that describe a trajectory of progress on the competencies from novice (entering resident) to proficient (graduating resident) and, ultimately, to expert/master.

The new educational milestones are “developmentally based, specialty specific achievements that residents are expected to demonstrate at established intervals as they progress through training. Residency programs in the NAS will submit composite milestone data on their residents every six months synchronized with residents’ semiannual evaluations”(2).

Milestones are shared understanding of expectations that map learning experiences to the six core competencies. Milestones serve as metrics across the learning continuum from student to practitioner, providing a rich source of longitudinal tracking and monitoring of important quality indicators that define the educational outcomes of the residency program.

Milestones also match competencies with developmental readiness. In the NAS, programs are expected to document annual evaluation trends and continuing program progress assessment. The six core competencies will remain as anchors for the NAS milestones. The NAS levels comprise five stages of physician professional development, from novice to expert/master, hence Levels 1 to 5, described as follows:

Level 1—Novice: Expected competencies of a graduating medical student

Level 2—Advanced Beginner: Expected competencies of end of physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R) postgraduate year (PGY) 1 resident

Level 3—Competent: Expected competencies of end of PM&R PGY 2-year resident

Level 4—Proficient: Expected competencies of end of PM&R PGY 3 graduating resident prepared for unsupervised practice

Level 5—Expert: Expected competencies of advanced resident fellow specialist and practicing physician

The foundation and origins of the five progressive levels of medical education and physician professional development endorsed and adopted by ACGME’s NAS were adapted from and first described in the literature by the Dreyfus brothers in 1980 (3), as illustrated below.

Novice—Follows rules (knows right from wrong): Don’t know what they don’t know—Level 1

![]()

Advanced Beginner—Rules + situation: Know what they don’t know—Level 2

![]()

Competent—Rules + selected contexts + accountable: Able to perform tasks and roles of the discipline—restricted breadth and depth—Level 3

![]()

Proficient—Accountable + beginning intuitive; immediately sees what: Consistent and efficient in performance of task and roles of discipline—know what they know and don’t know—Level 4

![]()

Expert—Immediately sees how; has seen many patterns: In-depth knowledge of discipline—know what they know—Level 5

![]()

The process of learning any new skill can be divided into four stages, illustrated as follows, described in 1990 by Neil Whitman (4). These descriptions of learning stages were initially adapted from Noel Burch in the 1970s describing the four stages for learning any new skill. The literature also attributed this model to the founder of humanistic psychology Abraham Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs” in the 1940s (5).

Unconscious Incompetence (Novice): Don’t know that they don’t know—Level 1

![]()

Conscious Incompetence: Know that they don’t know—Level 2

![]()

Conscious Competence: Know what they know and don’t know—Level 3/4

![]()

Unconscious Competence (Expert): Know what they know and don’t know that they know—Level 5

MILESTONE EXPECTATIONS AND REPORTING

Milestones consist of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and other attributes for each of the ACGME competencies organized in a developmental framework from less to more advanced. As a resident progresses from entry into residency through graduation, milestones serve as descriptors or markers and targets for performance expectations.

The NAS expects every residency program to establish a CCC whose responsibility is to assess the milestones. The CCC’s role is to establish guidelines and thresholds to ascertain whether a resident is competent, and provide supporting information and evidence as to competency. The key characteristic of the CCC is that the member group collectively makes competency decisions through multiple broad consensus, not relying on just the program director or rotation supervisor’s judgments. Decisions relating to competency and progressive advancement will be based on dashboards of collective and summative data, and through group conversations and wisdom. Also, if a resident is judged to be deficient in competencies and not achieving the milestones requirements, the remediation strategy is relegated to the CCC. Warnings, probation, repeating rotation, or counseling to consider another specialty or profession’s decisions might be options available to the CCC.

Historically, there has been a disconnect between graduate medical education (GME) and chief executive officers of medical centers. ACGME’s NAS attempts to address this issue. Academic Institutional Reviews by ACGME of residency sponsoring bodies will now be conducted through the new NAS’s CLER, authorized to implement continuous workplace monitoring and assessment. It is estimated that 80% of medical errors are systems based. CLER visits are scheduled every 18 months by a team of visitors, and these engage a different site each visit. CLER will focus on the six domains of (a) quality improvement, (b) patient safety, (c) supervision, (d) transitions of care, (e) duty hours/fatigue management, and (f) professionalism (6,7).

Institutional procedures and outcomes will be reviewed. CLERs will observe and evaluate daily operations by conducting “walk-arounds” of the institution and interview residents, faculty, administrators, quality and safety point persons, nurses and other allied health members, and executives. Significantly, CLERs will engage and interact with and survey chief executive officers, deans, designated institutional officials (DIOs), chief financial officers, chief medical officers, and chief nursing officers, commonly referred to as the “C and D suites.”

Milestones are organized into 5 numbered levels. Tracking and monitoring residents from Level 1 to Level 5 coincides with moving from novice (Level 1) to expert (Level 5). These five levels do not correspond with PGY of education, as residents nationally are exposed to clinical experiences during different residency years. Also, milestones are just one source of information for graduation decision making. Ultimately, the program director will have to make a judgment, based on CCC’s input, whether the resident “has demonstrated sufficient competency to enter practice without direct supervision.”

Residency programs will use milestones as a reporting mechanism for each period. Such a process is designed for programs to use in semiannual review of resident performance and reporting to ACGME. Upon a program’s submission of milestones assessments, the ACGME generates a milestones evaluation report for the program. In the initial years of milestones implementation, the RRC will examine milestone performance data for each program’s residents as one element in the next accreditation system (NAS) to ascertain whether residents overall are progressing as expected. For a given program, the review committees will compare aggregate program-level data and de-identified milestone data for resident performance against cohorts longitudinally.

Programs will have to review and report for each semiannual period the selection of milestone levels that best describe each resident’s current performance and attributes. Selection of a level connotes that the resident substantially demonstrates the milestones in that level, as well as those in lower levels; in other words, a hierarchical structure. For example, a resident demonstrating Level 3 competency is also expected to have demonstrated Levels 1 and 2.

Descriptions of the Milestones Levels (8) are as follows:

Level 1: The resident demonstrates milestones expected of an incoming resident.

Level 2: The resident is advancing and demonstrates additional milestones, but is not yet performing at a mid-residency level.

Level 3: The resident continues to advance and demonstrates additional milestones consistently, including the majority of milestones targeted for residency.

Level 4: The resident has advanced so that he or she now substantially demonstrates the milestones targeted for residency. This level is designed as the graduation target, but does not represent a graduation requirement. Making decisions about preparedness for graduation is the purview of the residency program director. Over time, study of milestones performance data will be necessary before the ACGME and its partners will be able to determine whether milestones in the first four levels appropriately represent the developmental framework, and whether milestone data are of sufficient quality and rigor to be used for high-stakes decisions.

Level 5: The resident has advanced beyond performance targets set for residency and is demonstrating “Aspirational” goals, which might describe the performance of someone who has been in practice for several years. It is expected that only a few exceptional residents will reach this level.

Progressive implementation of the NAS for ACGME/RRC reviews is being phased in between July 2013 and July 2014 for all 26 ACGME-accredited core specialties. The NAS for PM&R will be phased in beginning July 2014. With respect to the reliability and validity of the milestones—which were developed by working groups of ABMS board members representing major stakeholders—construct, criterion, and predictive validity will be established over time with accumulation of national data (9).

The ACGME/RRC’s NAS is characterized by compliance requirements for ongoing annual data collection, tracking and monitoring of evaluation and assessment trends of residents, programs in key performance, and learning outcomes measurement markers. An expected prominent feature of the NAS is to facilitate opportunities for early identification of suboptimal performance. Residency programs will be expected to report aggregated milestone data for their residents every 6 months, synchronized with residents’ semiannual evaluations.

The milestones and levels of resident learning outcomes are being defined by each specialty and developed by expert panels. Graduates of all residency programs will have to demonstrate achievement of the required milestones before graduation and entry to unsupervised practice, documented by the programs as the final graduation milestones.

As of this writing, the PM&R RRC has drafted 27 sets of milestones across the 6 domains of core competencies, distributed as follows: patient care (7), medical knowledge (9), professionalism (3), interpersonal and communication skills (2), practice-based learning and improvement (3), and systems-based practice (3).

TEACHING AND FEEDBACK

Multigenerational Workforce

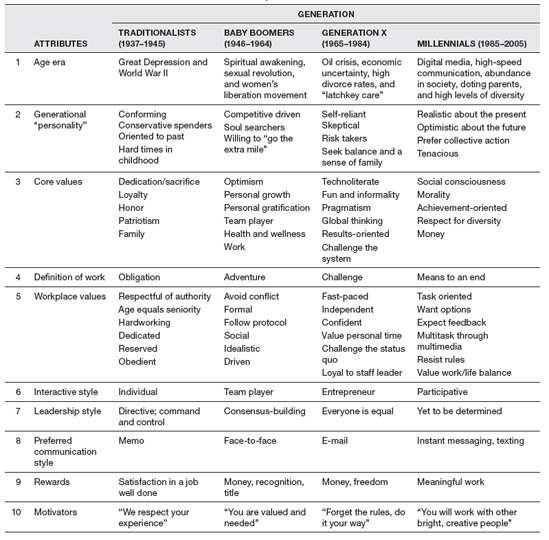

In today’s workplace landscape, working effectively together across generations requires sensitivity to, and understanding and appreciation of, the typical attributes of each generation. Generational characteristics such as preferred communication style, leadership styles, rewards, motivators, interaction styles, workplace values, core values, definitions of work, and generational “personalities” have profound implications for learning and teaching outcomes across generations. Unless we are aware and prepared to adapt to these generational differences, we will have missed teaching/learning opportunities and will not do our jobs effectively as educators.

Attendings and residents encompass four age eras: (a) Traditionalists (born between 1937 and 1945), (b) Baby Boomers (born between 1946 and 1964), (c) Generation X (born between 1965 and 1984), and (d) Millennials or Generation Y (born between 1985 and 2005). Table 4.1 describes the top 10 multigenerational attributes (10).

What Does It Mean to Teach?

In the age of NAS, teaching and assessing the core competencies is a priority and should be seamlessly integrated with all teaching methods, didactics, journal clubs, mortality and morbidity conferences, seminars, hands-on procedural instruction, and so on.

Think back and remember an exemplary teacher. What qualities and characteristics demonstrated by the teacher influenced your learning? Some of these memorable qualities might be skills in inspiring and “igniting the learning fires,” motivating and challenging students, and having the ability to engage and excite the learner and evoke enthusiasm about the content being taught. In fact, these are the same qualities of an effective teacher.

The effective teacher displays skills in creating a “want and need to know” environment. These educators “don’t tell” or “don’t spoon feed” information, but rather “guide the learner to answers.” This is typically known as the Socratic teaching method. Socrates, the Greek philosopher and teacher, was exemplary in pioneering teaching techniques through effective questioning skills, rather than “telling.”

The term doctor is derived from the Latin word docer meaning “to teach.” The 4th-century Hippocratic Oath enjoins the physician to teach the craft of healing to younger colleagues. Demonstrating effective teaching skills and the art of teaching draws upon the science of education and is process oriented.

Scholarship is a pillar of professional development. Boyer and Glassick articulated the meaning of scholarship and remind us that physicians must demonstrate competency and commitment to scholarship, including the scholarship of teaching (11–13). The ACGME has adopted Ernest Boyer’s definition of the three types of scholarship (11): (a) the scholarship of discovery (peerreviewed funding, peer-reviewed publication of original research), (b) the scholarship of dissemination (review articles or chapters in textbooks), and (c) the scholarship of application (publication or presentation of case reports, clinical series, lectures, workshops at local, regional, or national meetings; or leadership roles in professional or academic societies). For clarification, being scholarly means “improving on others and self,” while doing scholarship is to advance the field.

Effective teaching components consist of the content to be taught, the learner’s attributes and characteristics, and the context within which teaching takes place. The ultimate goal of effective teaching is “delivering the right learning, to the right learner at the right time!” The role of the effective teacher is to take a complex body of knowledge (content) and communicate that at the appropriate learner development stage and level of understanding (learner—Dreyfus Levels 1–5, novice to expert), learner’s preferred learning styles (learner), within the particular teaching context, such as didactics, seminars, clinical venue, bedside, journal clubs, or hands-on procedure practicum (context).

Clearly, residency and fellowship programs have an obligation for commitment to education and teaching. Teaching is an expectation and a competency in physician education, and monitored by accreditation bodies such as ACGME (responsible for residency, fellowship, and institutional accreditation) and Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME; responsible for medical school accreditation). The residents and fellows are student learners first and foremost, and the faculty member’s teaching mission must be to create and protect space and environment for teaching and learning. The resident/fellow learner must engage in an iterative cycle throughout the residency, reflecting on the following 3 questions: (a) What am I doing? (b) How am I doing? and (c) How can I improve? In fact, this quality improvement cycle is repetitive throughout the continuing professional development of the physician beyond training well into the Maintenance of Certification (MOC) and Maintenance of Licensure (MOL) phases.

TABLE 4.1 Characteristics of the Four Generations Currently in the Workforce

The ACGME is very sensitive to the balance between teaching/learning/education and service rendered by the resident. Despite the importance given to teaching by ACGME and the RRCs, protected teaching time and creating incentives for teaching remain challenges. DaRosa (14) cited major barriers to effective teaching by faculty members, such as lack of faculty development opportunities, attitudes and values faculty might have toward teaching, competition with clinical revenue generation, and limited commitments.

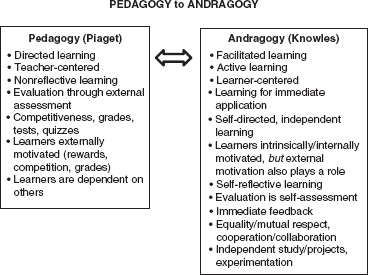

Adult Learning Principles and Practice

The foundation of physician learning is embedded in adult education principles and practices, or andragogy (15). The life span of learning is a continuum that moves from pedagogy [how children learn, as articulated by Jean Piaget (16), renowned cognitive child developmental psychologist) to andragogy (how adults learn, as described by Malcolm Knowles (17,18), father of adult education, and Cyril Houle (19)], each with distinct characteristics illustrated in Figure 4.1.

As reflected in Figure 4.1, adults learn best when:

They are enabled to be actively involved in the teaching/learning activity.

They are enabled to be actively involved in the teaching/learning activity.

Their personal model of reality is acknowledged and respected, allowing them to pursue their own learning goals, self-reflection, and fostering and supporting self-directed learning.

Their personal model of reality is acknowledged and respected, allowing them to pursue their own learning goals, self-reflection, and fostering and supporting self-directed learning.

Learning that matters is relevant, practical, meaningful, and relates to current tasks, experiences, actual problems, or issues, with immediate direct application.

Learning that matters is relevant, practical, meaningful, and relates to current tasks, experiences, actual problems, or issues, with immediate direct application.

Immediate feedback is provided; adults want to know how they are doing.

Immediate feedback is provided; adults want to know how they are doing.

Learners’ past experience, knowledge, skills, values, and motives are deployed to their existing roles, responsibilities, and resources for learning.

Learners’ past experience, knowledge, skills, values, and motives are deployed to their existing roles, responsibilities, and resources for learning.

FIGURE 4.1 Learning Continuum Over a Life Span

Learners treated according to their professional stage identities, developmental readiness, roles/responsibilities, who they are, and their capabilities.

Learners treated according to their professional stage identities, developmental readiness, roles/responsibilities, who they are, and their capabilities.

Learners are clear about where they are going, how they will get there, and how they will know when they got there and have succeeded.

Learners are clear about where they are going, how they will get there, and how they will know when they got there and have succeeded.

Practice-based learning and improvement (PBLI), one of the six core competencies, is the cornerstone of adult learning and self-directed learning. Lifelong learning (LLL) and self-assessment are hallmarks of adult learning and continuous professional development (CPD). LLL reinforces, expands, and improves core competencies. CPD is the “chronic” habit of looking at your own practice over time longitudinally and comparing it to peers and to acceptable national standards. ABMS’s Maintenance of Competency (MOC) and FSMB’s (Federation of State Medical Boards) MOL are embedded in a culture of continuous learning, practice improvement, and opportunities for self-directed learning and self-assessment. Competencies for LLL address what you are doing, how you are doing, and how you can improve. Specifically, LLL habits include (a) drawing upon high-quality unbiased evidence-based health care literature and critical thinking; (b) application of clinical and educational information; (c) literature search and retrieval strategies; (d) PBLI methods; (e) self-reflection (developing analogies and new mental models, and improving practice from moving from old to new ways of practicing) and assessment; and (f) skill sets for learning management, drawing upon one’s own resource for learning and knowledge management (learning-how-to-learn).

Effective Teaching and Teaching Competencies Strategies

Some common teaching methods and environments during residency include lectures and seminars (didactics); journal clubs; grand rounds; inpatient; outpatient; consultations; bedside teaching; case conferences (case-based learning); handson procedures such as electromyography (EMG) and injections (psychomotor); clinics; objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs); standardized patients (SPs), simulations, actors; and problem-based learning (PBL).

We were brought up in a didactic education world and U.S. medical education is no exception, characterized by predominately being lectured to, referred to as “passive learning.” As educators, we know that we should promote a variety of modes of instructional delivery. David Davis’s (20) study informs us that highimpact instructional formats that are more likely to result in desired behavior/attitude change when compared to traditional didactic lectures have the following characteristics in common: learner-centered, interactive, meaningful/relevant/personal, reinforcing, successive or repeated, and mixed methods teaching. Foley and Smilansky (21) over 30 years ago informed us that 80% of information delivered by lectures is forgotten within 8 weeks, and that after 20 minutes of lecture, the learner’s attention drops dramatically. The lecture is the weakest method for changing behavior.

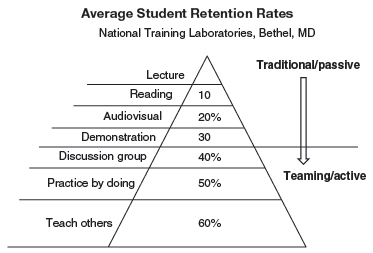

“Tell me and I’ll forget; Show me and I may remember; Involve me and I’ll understand.” This Chinese proverb reminds us that learning is dramatically improved when the learner actively does a task, discusses what is taking place, practices, and teaches others, referred to as “active learning.” As illustrated in the Learning Retention Pyramid (22), Figure 4.2, retention rate improves progressively as you more actively involve and engage the learner as when you move from passive to active learning. Figure 4.2 demonstrates that we remember only 10% of what we read, 20% of what we hear, 30% of what we see, 50% of what we hear and see (as when we engage in discussion), 70% of what we practice by doing, and 90% of what we teach others.

FIGURE 4.2 Learning Retention Pyramid

Teaching is as much an art as it is a science. Artful teachers have the ability to leverage subtle manipulations of emotion, in addition to being content experts. Proficient teachers invariably display the following qualities: (a) establish rapport with learner, be supportive, be accessible, be compassionate, and be organized; (b) create optimal student–teacher dynamics and relationships with frequent exchanges that enlist mutual trust and respect and individual consideration; (c) have passion for teaching; ability to excite, motivate, generate enthusiasm, and emotionally activate learners; (d) early on set up goals, directions, and expectations, and target teaching to learners’ level of knowledge and developmental preparedness; (e) give feedback and expect feedback in return; engage in self-evaluation and reflect on one’s own teaching; and (f) demonstrate mastery and competence in subject matter being taught.

Learning Styles

As previously stated, the effective teacher considers a learner’s preferred learning styles. Educators have known for many years that learning styles affect the way we learn. Highlighted are three well-known assessments used in medical education to identify preferred learning styles and personality indicators: (a) Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) (23). MBTI is one of the most commonly used psychological personality tests that maps individuals across four sets of coordinates across a continuum: Extroversion (E) ↔ Introversion (I), Sensing (S) ↔ Intuition (I), Thinking (T) ↔ Feeling (F), and Judgment (J) ↔ Perception (P). This excellent instrument can be used to identify and, if desired, intentionally match personalities among residents or faculty, or between faculty supervisor and resident. (b) Kolb’s Learning Style Inventory (24): This indicator identifies individuals across four dimensions—Convergers, Divergers, Assimilators, and Accommodators. (c) The third inventory tool well validated in the health professions is the Rezler Learning Preference Inventory (RLPI) (21): This is useful in identifying conditions and situations that facilitate individual learning and types of learning situations preferred by the learner. This instrument describes how you learn best, but does not evaluate your learning abilities. Scores reflect how you learn across three sets of continuum: Abstract (AB) ↔ Concrete (CO), Teacher-Structured (TS) ↔ Student-Structured (SS), and Interpersonal (IP) ↔ Individual (IN). AB learners prefer learning theories, general principles, and concepts, as well as generating hypotheses. CO learners prefer learning tangible, specific, practical tasks and skills. TS learners prefer well-organized, teacher-directed objectives, with clear expectations, assignments, and goals defined by the teacher. SS learners prefer learner-generated tasks, are autonomous, and are self-directed. IP learners prefer learning or working with others; emphasis is on harmonious relations between students and teacher and among peer learners. IN learners prefer learning or working alone, with emphasis on self-reliance and tasks that are solitary, such as reading or interacting with computers.

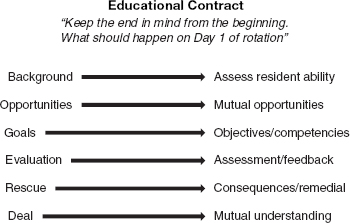

Feedback and Educational Contract

The practice of drawing up an “educational contract” between the resident learner and attending supervisor and in providing feedback is extremely useful and important in order to lay out mutual expectations, avoid setting up learners for failure further into the rotation, and ensure a “win–win” situation. “BOGERD” is an acronym for a six-step process described by Bulstrode and Hunt (25) that establishes a teacher–learner education contract that keeps the end in mind from the beginning, as in Day 1 or beginning of the rotation, and is explicit about mutual obligations.

B represents Background assessment of a resident’s abilities. Invest the time upfront to assess the resident during the first several days or week of the rotation to observe and determine individual strengths and limitations. Begin with a comprehensive assessment of the resident’s capabilities and competencies (baseline data) when beginning a rotation, using tools such as knowledge tests, direct observation of skills, Resident Observation and Competency Assessment (RO&CA), Global evaluations, Resident Self-Assessment, and Summative Competency-based evaluation, to name a few. Based on these results, aim teaching to address training needs during the rotation, considering the resident’s strengths and weaknesses.

O stands for disclosing and sharing expected Opportunities during the rotation, and seeking feedback on opportunities that the resident might be expecting.

G, or Goals, is formally articulating on Day 1 or at the beginning of rotation what the rotation covers, such as learning objectives, Dreyfus resident level-specific competencies, and milestones.

E is Evaluation informing the resident as to how (e.g., global evaluations, RO&CAs, knowledge tests, multisource 360° evaluations, formative and summative evaluations) and how frequently they will be evaluated, as well as feedback expectations.

R, Remediation/Rescue, is to let the resident know what the consequences of not meeting rotation expectations will be and the remediation process, when necessary. And,

D is the contract Deal; validate to make sure the resident has fully heard and understands the BOGERD process you articulated and ask him or her to sign off on the learning contract or deal indicating approval by both resident and attending supervisor. This process is illustrated Figure 4.3.

Competency-Based Journal Club

A novel method for teaching core competencies while conducting Journal Clubs in a seamless fashion is described as follows.

1. Residents choose two journal club articles on the topic assigned, of their own choosing, or those designated by their supervisor.

2. The articles must have been from within the past 5 years, unless they are considered classical articles and are still meaningful and relevant.

3. These articles must be chosen at least 4 weeks prior to the journal club and approved by the faculty supervisor.

4. After the attending supervisor approves the articles, residents prepare their presentations.

5. Articles are distributed to all residents and faculty in advance of the journal club date.

6. Presentations may be informal or formal using PowerPoint, although not required.

7. It is expected that all the residents and faculty attending the educational activity will have read the articles.

8. Presentations are expected to be a brief overview of the key elements of the paper, which will then be followed by a discussion.

The following questions should be answered in the journal club (recommend 25–30 min per article, with the suggested time breakdowns as follows):

1. What questions is the article trying to answer (hypotheses)? (1–2 min)

FIGURE 4.3 BOGERD Process

2. Why are the authors trying to answer this question (relevance)? (1–2 min)

3. What is the study design (design)? (2 min)

4. What are their methods (methods)? Include a brief description of the statistical approach (5 min).

5. What did they find (findings)? (5 min)

6. Critique of methods and conclusions (5–10 min)

7. Is this applicable and relevant? Implications for further investigation? Why? (5 min)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree