Aphalangia and Amniotic Band Syndrome

CASE PRESENTATION

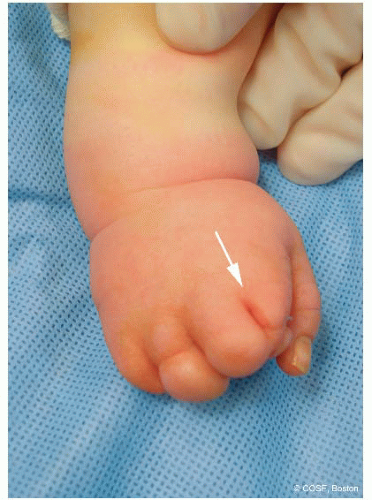

A 1-month-old infant presents for evaluation of a “hand defect.” At birth, the child was noted to have congenital differences of the hand, including “extra skin creases” and the absence of the digital tips (Figure 9-1). Despite the abnormal appearance, the digital tips have always appeared pink. No obvious abnormalities have been noted in the proximal hand or remainder of the affected upper limb. The other three limbs are normal by exam as is a complete organ system exam by the pediatrician.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

What is amniotic band syndrome (ABS)?

What is the etiology of ABS?

What are the clinical features of ABS, and how is it distinguished from symbrachydactyly?

How is ABS classified?

What are the treatment principles?

What are the surgical techniques utilized for aphalangia?

What are the treatment principles for congenital below-elbow amputations?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

Etiology and Epidemiology

Also known as constriction band syndrome, constriction ring syndrome, Streeter dysplasia, and limb-body wall malformation complex, ABS is thought to affect 1:1,200 to 1:15,000 live births.1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 Males and females are equally affected. In some series, up to 60% of cases have an associated identifiable event during pregnancy.3 No hereditary predisposition has been identified.

There are two theories regarding etiology. Streeter first proposed the intrinsic theory, suggesting that ABS results from an abnormality in the germplasm differentiation and development.6 Accordingly, a defect in differentiation —perhaps from teratogenic exposure, viral infection, or vascular disruption—causes necrosis and band formation.7, 8 and 9 Torpin was among the first to advocate an extrinsic cause of ABS.10 In this theory, the amnion ruptures and free-floating strands of membrane entangle, constrict, deform, and/or amputate affected parts. At the same time, the exposed chorion absorbs the amnionic fluid and induces a transient oligohydramnios, resulting in even further external compression on the developing limb. (This may in part explain the association of ABS with other “packing” disorders, such as congenital clubfoot.) Experimental studies have demonstrated the ability to reproduce similar phenotypes, supporting the extrinsic theory.3,11, 12, 13 and 14 We, like most authorities, subscribe to the extrinsic theory of causation.

Clinical Evaluation

Patients with ABS may present with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. Hand findings range from subtle dimpling or indentations of the skin, constriction bands with distal lymphedema, and acrosyndactyly to absence of distal amputations. Despite the range of findings, a number of clinical features are characteristic.3,15,16 First, the bands typically lie transversely, orthogonal to the longitudinal axis of the digit or limb. Second, central digits tend to be more affected than border digits due to their natural increased length. Third, the majority of constriction bands affect the digits; forearm or brachium involvement is much less common. Level of involvement may depend upon the timing of amnionic disruption and entrapment.13 These clinical findings are consistent with the extrinsic theory of causation.

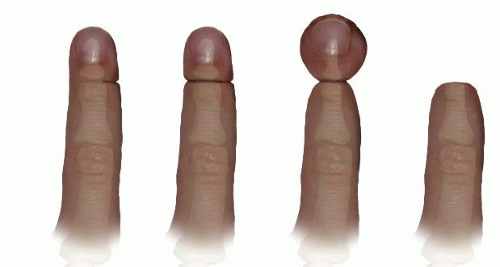

In cases of ABS where the band is severe enough to cause “autofusion” of adjacent digits but not so deep as to result in amputation of distal parts, acrosyndactyly may occur.17 While the exact mechanism is unknown, distal hemorrhage, superficial tissue loss, and scarring and fusion of distal segments have been theorized.12 Unlike complex syndactyly due to failure of differentiation, the acrosyndactly of ABS usually occurs without bony fusion and typically exhibits a sinus tract at the base of the affected digits that passes from dorsal to volar (Figure 9-2). This sinus tract lies distal to the level of the normal web commissure. Often the digital tips are closely apposed and collectively resemble a “bunch of grapes.” In these situations, the orientation of the digits is confusing, and it is often difficult to ascertain which digital tip belongs with each digit. In cases like these, the long finger tip is usually most palmar.18,19

FIGURE 9-2 Illustration of the interdigital sinus tract typical of the acrosyndactyly seen in amniotic band syndrome. |

Although ABS is thought to represent a deformation of a normal digit with therefore normal underlying anatomy, there may be distal nerve dysfunction and/or vascular insufficiency. Nerve dysfunction and distal sensory defects may be due to neurapraxia. Furthermore, in some cases, a temperature gradient may be noted across the band, with the distal segment having lower temperature, diminished capillary refill, and edema. This is due to vascular insufficiency related to the band. There are rare situations in which the band is still present at birth and causes acute vascular compromise. These bands should be removed or incised in the nursery.

Associated conditions have been noted in up to 80% of patients. Concomitant congenital hand differences include syndactyly, hypoplastic digits, camptodactyly, and brachydactyly. Other congenital differences, including cleft lip, cleft palate, clubfoot, and craniofacial defects, are similarly seen in patients with ABS.10,20

While a number of classification systems have been utilized, that of Patterson is the most descriptive and commonly utilized7 (Figure 9-3). Type 1 denotes simple amnionic bands with superficial skin involvement only. Type 2 refers to bands with distal deformity or lymphedema. Type 3 ABS is associated with acrosyndactyly. Type 4 is the most severe and denotes congenital amputations.

Surgical Indications

Learn to differentiate between what is truly important and what can be dealt with at another time.

—Mia Hamm

Given the broad spectrum of clinical findings and/or associated conditions, the treatment of ABS remains highly individualized from patient to patient. However, a number of guiding treatment principles are proposed. Superficial bands with aesthetic differences but no functional impact may be treated electively with band release using skin and soft tissue rearrangement (e.g., Z-plasties). Deeper bands resulting with lymphedema or distal deformity are treated accordingly with similar soft tissue techniques, though this is often pursued when the patient is younger, to maximize function and eliminate distal changes. Syndactyly or acrosyndactyly is treated with surgical releases with web-space reconstitution, skin rearrangement, and/or skin grafting. Finally, patients with distal ischemia due to the tourniquet-like effect of a very deep amnionic band are treated emergently to avoid tissue loss and secondary complications such as infection. Interestingly, Flatt19 has reported that the effect of bands may not be static, as the underlying granulation tissue may cause progressive constriction and late vascular insufficiency.

Similar to the principles of syndactyly release, caution is advised whenever both sides of the digit are operated upon in a single setting. While single-stage circumferential releases may be considered for superficial bands,

two-staged releases (50% band release at first procedure, followed by completion of the release 6 weeks to 3 months later) may be more judicious in patients with deep bands to avoid vascular embarrassment.16,19,21,22

two-staged releases (50% band release at first procedure, followed by completion of the release 6 weeks to 3 months later) may be more judicious in patients with deep bands to avoid vascular embarrassment.16,19,21,22

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

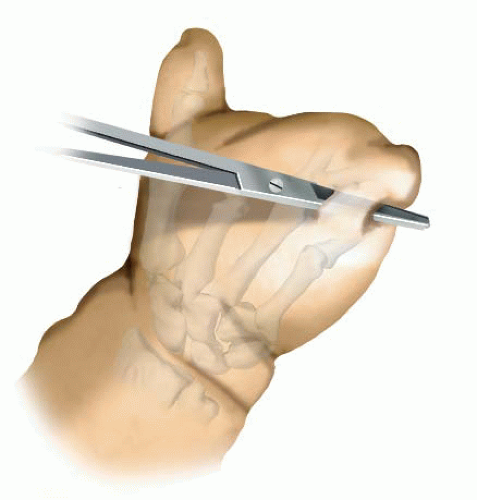

Removal of Band in Office or Nursery

The only potential emergency in infancy is vascular compromise from an amnionic band acting like a venous tourniquet. In this situation, the band will be a darkened ring around the finger. It can be teased off the digit(s) with a surgical pickup. Alternatively, a longitudinal incision may be made through the constriction, releasing the tourniquet-like effect of the amnionic band. This situation is rare but important. The procedure may be performed in the nursery without anesthesia and can lead to immediate improvement in vascularity if performed early enough.

Acrosyndactyly can be due to bands that forced the connection of all digits. These are usually associated with congenital amputations. Early in infancy, separation back to the sinus tracts of all digits is not a risk for vascular compromise. The result can be very dramatic, especially with liberation of the thumb. Release from each sinus tract distally will mobilize the first, second, and fourth web spaces. Often the long and ring fingers need to stay initially conjoined. Later reconstruction is usually necessary, but this procedure in the first few months of life allows for more refined active use of the hand.

▪ Simple Band Excision and Z-Plasties or Rotation Flaps

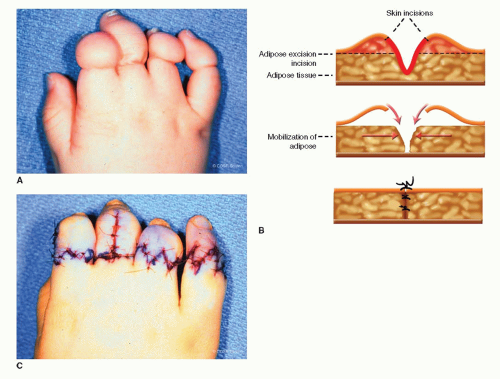

Under general anesthesia, tourniquet control, and loupe magnification, simple bands may be excised with 60-degree Z-plasty flaps to confer soft tissue coverage without inducing secondary scar contractures. Z-plasties in series or excision of constriction band with careful elevation of skin flaps is performed (Figure 9-4). While the subcutaneous fat is kept on the flaps in an effort to preserve vascularity, any identifiable deep veins or superficial nerves are longitudinally preserved during the initial, careful dissection. This is especially critical for deep bands on the volar aspect of the digit, as the neurovascular bundles may be closely apposed to the constriction band and underlying bone and difficult to visualize. Plans should also be made to excise the constriction band, rather than incorporating this abnormal tissue into the rotating flaps. To restore a smooth, more normal contour to the affected digit, subcutaneous fat is mobilized to provide adequate soft tissue coverage, and excess tissue at the leading edge of the flaps is judiciously debulked.23 Simple band excision and circumferential skin closure is not recommended as it will result in subsequent scar contracture and “recurrence.”

♦ Nonvascularized Toe Phalangeal Transfer

Hit the shot you know you can hit, not the one you think you should.

—Dr. Bob Rotella

In cases of aphalangia—due to ABS, symbrachydactyly, or transverse deficiency—nonvascularized toe transfers may be considered. In these situations, a toe phalanx with its surrounding periosteum is taken from the foot and transferred to the soft tissue “nubbin” or pocket of the affected digit(s). By increasing the length of the affected digit, function of the hand may be improved. This procedure takes advantage of the general principles that all sensate digits will be utilized by the child, more digits provide better function than fewer digits, and digital length is important for digital function.

Indications for nonvascularized toe transfers include (1) aphalangia of the thumb with absent digits at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) level, (2) bilateral hand/finger involvement, or (3) intercalary bone defects, particularly of the thumb. Relative contraindications include absence of the metacarpals and single digital involvement. A soft tissue “nubbin” of adequate size that can accommodate the transferred bone is a prerequisite to surgery. Furthermore,

early surgery is advocated, preferably before 12 months of age; multiple studies have demonstrated higher rates of physeal growth in transplanted phalanges when surgery is performed in younger patients.24,25

early surgery is advocated, preferably before 12 months of age; multiple studies have demonstrated higher rates of physeal growth in transplanted phalanges when surgery is performed in younger patients.24,25

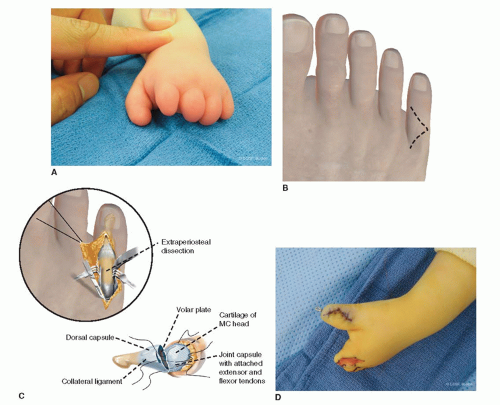

Surgery is performed under general anesthesia and tourniquet control (Figure 9-5).26,27 Dorsal zigzag or chevron incisions are created on the affected digit. Soft tissue dissection is performed down to the level of the extensor mechanism, which is incised longitudinally. Usually, the extensor and flexor tendons may be conjoined and confluent. Care is made to preserve the soft tissue “cap” at the distal aspect of the nubbin, to avoid devascularizing the digital tip. Blunt dissection is then performed via gentle longitudinal spreading, creating a soft tissue pocket or cavity to accept the toe phalanx. The dimensions of this recipient site are then measured.

Direction is then turned to the foot. Typically, the proximal, less commonly middle, phalanges of the second, third, and/or fourth toe(s) are harvested depending on how many phalangeal transfers are planned. Bilateral foot harvesting can occur for later symmetry of appearance. Ultimately, the choice of the extraperiosteal bone(s) to be transferred is based upon parental preference, careful preoperative planning, and intraoperative measurements of the recipient soft tissue pocket. (It is helpful to measure the length and width of the toe phalanges on a preoperative foot radiograph and have these measurements readily available during surgery.) A dorsal chevron incision is created over the desired toe phalanx. The toe extensor mechanism is also split longitudinally. With care being made to preserve the periosteum, the collateral ligaments are released, preserving length proximally for transfer and revascularization. Once the distal articular surface is liberated, distal-to-proximal extraperiosteal dissection is performed. The plantar plate and then pulleys must be released, with preservation of the underlying flexor tendons and neurovascular bundles of the toe. The toe phalanx is then released from the more proximal joint, allowing for transfer. The collateral ligaments and plantar plate attachments are preserved at the proximal end of the phalanx for attachment to the metacarpal during transfer. In the donor toe, the extensor may be sewn to the flexor tendon to close the defect and preserve length and alignment prior to wound closure.28

FIGURE 9-5 Technique of nonvascularized toe phalanx transfer. A: Clinical photograph of a patient with aphalangia depicting the structural deficiencies. Note the substantial soft tissue nubbins at the end of the digits, which are prerequisites for this technique. B: Schematic diagrams depicting incisions over the hand and foot. Usually the middle toes (2nd, 3rd, 4th) are used for non-vascularized phalangeal transfer. C:

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|