Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction with Patellar Tendon Autograft: Surgical Technique

Bruce S. Miller MD

Edward M. Wojtys MD

History of the Technique

The natural history of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) insufficiency in an active individual has been well described and includes recurrent functional instability, failure of secondary restraints, meniscal and chondral injuries, and the subsequent development of arthrosis.1,2 Consequently, surgical treatment is frequently indicated in those who are physically active. Early efforts at anatomic repair of the injured ACL resulted in poor functional outcomes.3 As a result, direct repair is presently reserved primarily for distal tibial avulsion fractures. Several factors have led to the emergence and popularity of modern techniques for reconstruction of the ACL.

Numerous extra-articular reconstructive procedures have been described for ACL insufficiency. Unlike present intra-articular anatomic ACL reconstructive techniques, these extra-articular procedures were intended to address instability by tightening secondary restraints, most commonly on the lateral side of the knee. Tenodesis of the iliotibial band in some fashion was the most common extra-articular procedure. Presently, extra-articular techniques are rarely employed and are reserved primarily for supplementation of intra-articular reconstructions in the presence of severe laxity of secondary restraints.

The goal of intra-articular ACL reconstruction is to anatomically replace the torn ligament with a biologic graft. Many graft types, including autograft, allograft, and occasionally synthetic devices, are currently implanted using a similar arthroscopically assisted surgical technique.

Indications and Contraindications

Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is indicated in those individuals with symptomatic instability of the knee who wish to return to sporting or occupational activities that require jumping, cutting, or pivoting activities. A patient’s desired activity level, rather than chronologic age, should guide the decision-making process. Thus, ACL reconstruction is certainly a viable option in the older ACL-deficient individual who desires to remain active. ACL reconstruction in the skeletally immature patient is commonly performed safely but is beyond the scope of this chapter.

ACL reconstruction may be contraindicated in the acutely injured knee. In the acute setting, resolution of pain and effusion, return of full range of motion, and complete recovery of quadriceps function should be the goal prior to surgical intervention. Unfortunately, meniscal and chondral injuries can make the preoperative goals difficult or even unattainable, creating a dilemma for the surgeon. Although one procedure is usually the goal to address all pathology present, if preoperative range of motion and function has been severely compromised, thought should be given to addressing these chondral or meniscal issues prior to ACL reconstruction. ACL reconstruction requires a challenging postoperative rehabilitation regimen and should not be considered in an individual who is unwilling or unable to meet this challenge.

The patellar tendon autograft is an excellent graft option for most patients. However, a history of patellar tendonitis, chronic anterior knee pain, or the presence of significant patellofemoral degenerative disease in the injured extremity may be considered a relative contraindication to the use of this graft.

Surgical Technique

Anesthesia and Positioning

The patient is placed supine on the operating table, and a thigh tourniquet is applied as proximal as possible on the

operative extremity. The patient’s pelvis should be moved toward the edge of the table to allow flexion of the knee off the side of the table during the operative procedure. A lateral post is applied to the table about the level of the junction between the middle and distal thirds to facilitate arthroscopic evaluation of the medial compartment.

operative extremity. The patient’s pelvis should be moved toward the edge of the table to allow flexion of the knee off the side of the table during the operative procedure. A lateral post is applied to the table about the level of the junction between the middle and distal thirds to facilitate arthroscopic evaluation of the medial compartment.

General or regional anesthesia can be employed for ACL reconstruction. However, we do not routinely advocate the use of regional nerve blocks for postoperative pain control, as these are usually unnecessary and may interfere with the patient’s ability to protect the knee against inadvertent injury in the immediate postoperative period. The combination of ketorolac tromethamine (pre- and postoperatively) along with intra-articular morphine and parenteral-local anesthetics appears to provide excellent pain relief when used in combination with oral analgesics.

A careful examination under anesthesia is a critical component of the surgical decision-making process. A side-to-side comparison of range of motion and ligamentous stability is imperative. Lachman, anterior and posterior drawer, varus-valgus stress maneuvers, rotation and patellar tests should be performed and recorded. The pivot shift test, which is often difficult to assess in the office setting, can be performed consistently in the operating room.

Surface Anatomy

Relevant anatomic landmarks include the patella, patellar tendon, tibial tubercle, and joint line. These landmarks can be marked at the beginning of the procedure to facilitate the graft harvest. In addition, sites of arthroscopic portals and incisions for possible meniscus repairs should be delineated.

Skin Incision

Use of the tourniquet is optional. Although its use may delay return of muscle function postoperatively, it can decrease operating time by facilitating visualization. The leg is exsanguinated and the tourniquet elevated prior to incision to facilitate visualization during graft harvest. The skin incision can be placed in several positions for patella tendon harvest. A medially based incision at the edge of the tendon may yield more cosmetic results. A central incision extending longitudinally from the inferior pole of the patella at midline to the medial aspect of the tibial tubercle is also acceptable (Fig. 35-1). The obliquity of the incision allows for adequate exposure for both graft harvest and tibial tunnel placement. If the patient’s occupation requires frequent kneeling, then the incision can be moved more medially to avoid potential irritation over the midline and tibial tubercle. The incision may disrupt fibers of the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve. As a result, the patient must be counseled to expect a small area of numbness lateral to the incision, which usually diminishes with time.

Graft Harvest and Preparation

The skin incision is carried sharply to the level of the peritenon. Transverse fibers can often be visualized in this layer and can help distinguish this layer from the longitudinal fibers of the patellar tendon below. The peritenon is divided longitudinally at midline and carefully dissected to reveal the medial and lateral aspects of the underlying patellar tendon. A ruler is then used to identify the central 10 mm of the tendon and a no. 11 scalpel is then employed to divide the tendon longitudinally in line with its fibers. A 10-mm wide by 20- to 30-mm bone plug (depending on patient size) is measured and marked at the tibial tubercle, with a similar plug marked on the distal pole of the patella. An oscillating saw is utilized with care to create the medial and lateral borders of a trapezoidal bone block from the tibial tubercle. The saw blade can be marked with tape at 10 mm to prevent deep cuts with the saw. The distal aspect of the bone block is also cut with the saw or prepared by multiple fenestrations with a drill bit. A straight, narrow osteotome is used to ensure completion of the osteotomy on all sides of the bone block, and the block is gently elevated off its tibial bed. With the knee in full extension to facilitate exposure of the patella, the oscillating saw is used to penetrate the dorsal cortex of the two sides of the proximal bone plug. The saw or drill is used to define the superior margin of the graft, and, with great care, an osteotome is used to complete the patellar harvest. Great care must always be taken in excising patellar tendon grafts. The fibers of the patella tendon frequently converge distally. Incisions across fibers render those fibers useless and decrease the functional width of the tendon. A poorly excised 10-mm graft can yield 6 or 7 mm of functional width. Narrowed grafts may leave the patient at risk for graft failure. Excess medial or lateral patella pressure, deep saw penetration, inappropriate use of osteotomes, and failure to bone graft defects can increase the likelihood of patella fracture. Most of these situations are avoidable and should be a central focus of each surgeon’s technique.

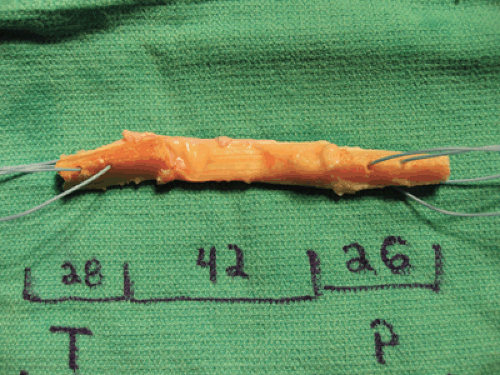

The graft can be prepared near the surgical site or on the back table. Caution should be exercised in either preparation site to avoid accidental mishandling or contamination of the graft. The bone plugs are usually fashioned to fit through 10-mm spacers, and no. 5 nonabsorbable sutures are passed through drill holes in the bone plugs to facilitate later graft passage (Fig. 35-2). The graft is wrapped in moistened sponges until implantation.

Arthroscopy

Standard arthroscopy portals are utilized for a thorough diagnostic evaluation of the knee. The menisci and chondral surfaces are inspected with great care, and all pathology is treated appropriately.

Excellent notch exposure is essential to proper graft placement. The tibial stump should be mostly, if not completely, removed. Stump remnants contain mechanoreceptors that may be of importance to the implanted graft. Consequently, efforts to preserve these fibers closest to the insertion may be worthwhile. The ACL remnant is cleared from the lateral intercondylar wall of the femur with a curette and shaving debrider to allow clear visualization of the over-the-top position. This position is identified by a veil of capsular tissue at the posterior aspect of the superior-lateral notch. This posterior position is often confused with a long ridge at the junction of the anterior two thirds and posterior one third referred to as the resident ridge. This ridge may function as a deflector for the ACL, providing a buttress to keep the ligament away from the lateral femoral condyle. Visualization posterior to the landmark is needed to properly position the graft, but complete removal of this ridge may be unwanted because of its suspected function. If the graft can be adequately positioned in this tunnel notch without bone resection, this approach is preferred. However, if there is evidence of notch stenosis, a formal notchplasty should be performed to improve visualization of the notch and protect the graft against impingement against the lateral wall or roof of the intercondylar notch.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree