Anterior Cervical Approaches

John Heflin

John M. Rhee

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Anterior Approach (Smith-Robinson)

The approach chosen depends on a number of factors, including the spinal segments that must be exposed, the nature of the procedure to be performed, and the patient’s body habitus.

In general, the Smith-Robinson approach allows access from C2 down to T1 in most patients. However, local variations in patient morphology may either limit or increase the extent of available exposure.

Ease of access to the C2-C3 disc depends on the location of the mandible and can be assessed on the preoperative lateral radiograph.

Nasal intubation is preferable when approaching this level as it allows the mandible to be maximally closed, away from the line of sight of the disc.

Depending on the location of the mandible with respect to C3-C4, nasal intubation may be preferable in certain instances of C3-C4 access as well.

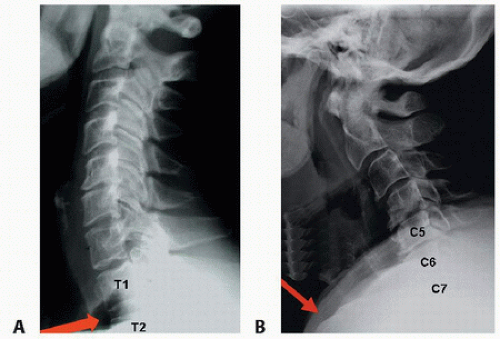

For pathology at C7-T1 or distal, careful scrutiny of the disc space with respect to the sternal notch on lateral radiographs will help to assess whether a sternal-splitting approach may be necessary.

In some patients with long necks, access to T2 or even T3 may be possible with a standard Smith-Robinson approach.

In those with short or stocky necks, even getting to C7 may be a challenge (FIG 1).

Imaging studies should be evaluated for anatomic variations such as medial aberrancy of the vertebral artery.

Considerable debate exists whether the “sidedness” of approach affects the rate of postoperative recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy. The literature is not conclusive but suggests higher rates with right-sided approaches.

If a patient has had prior neck surgery and it is desirable to approach the spine from the opposite side to avoid scar, a preoperative indirect laryngoscopy should be performed by ear, nose, and throat (ENT) consultation to rule out a recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy.

If one exists, the spine must be approached from the side of the injury to avoid the possibility of bilateral vocal cord palsy. If one does not exist, the spine can be approached from either side.

Lateral Retropharyngeal Approach (Whitesides)

This approach can be used for anterior access to the upper cervical spine but not the basiocciput.

It is often used for high cervical bony lesions, including tumors or infections for which a posterior approach is not possible, unstable fractures or dislocations with deficient or incompetent posterior elements, or posterior nonunions (particularly for fusions of C1-C2).

It is also useful for access to high cervical ventral or ventrolateral intradural lesions such as neurofibromas or meningiomas.

It allows unilateral access from C1 to C3. Access to the far contralateral side requires a second approach.

Potential complications include injury to the spinal accessory nerve and the vertebral artery. The jugular vein also lies within the operative field and can be a site of significant bleeding if inadvertently injured.

Significant retropharyngeal swelling has occurred and can result in prolongation of intubation if the patient’s airway becomes obstructed.

Anterior Approach to the Cervicothoracic Junction (Transmanubrial-Transclavicular Approach)

There are several different approaches for exposing the cervicothoracic junction, including the transmanubrial-transclavicular and the sternal-splitting (median sternotomy) approaches.

The sternal-splitting (median sternotomy) approach may be useful in providing improved distal access to the upper thoracic spine.

Deep dissection is essentially the same for the two approaches.

Cranial to caudal dissection is recommended to avoid injury to the major crossing vessels distally (eg, the left brachiocephalic vein).

With a left-sided approach, the thoracic duct is at greater risk. It passes into the left venous angle between the subclavian artery and the common carotid artery.

With a right-sided approach, the recurrent laryngeal nerve is at greater risk because of its greater variability versus the left side where the nerve is more constant in its location in the tracheoesophageal groove.

POSITIONING

Anterior Approach (Smith-Robinson)

The patient is positioned supine with the neck slightly extended.

The amount of extension tolerated by the patient without developing neurologic symptoms should be assessed preoperatively and not exceeded during positioning (FIG 2).

A bump (eg, rolled sheets) under the shoulders facilitates gentle extension of the spine.

A halter or Gardner-Wells tongs is optional but not routinely necessary for anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) surgery.

A foam doughnut is placed behind the occiput to prevent pressure necrosis.

The head is placed in neutral rotation. Doing so provides landmarks (the nose and the sternal notch) that are in line with the longitudinal axis of the spine for orientation during decompression and instrumentation.

Depending on the relationship of the mandible to the upper cervical spine, proximal approaches to C2-C3 may be easier if the head is gently rotated away from the side of the approach.

The amount of rotation should be kept in mind to prevent disorientation during surgery.

The shoulders are gently taped down to facilitate intraoperative radiographic visualization.

Excessive force should be avoided when taping down the shoulders to avoid brachial plexus injuries.

Spinal cord monitoring (eg, somatosensory evoked potentials [SSEP] and motor evoked potentials [MEP]) can be used to help prevent positioning-related nerve injuries, but it is not completely sensitive in detecting injury.

Lateral Retropharyngeal Approach (Whitesides)

The patient is placed supine with the head turned away from the side from which the approach will be performed unless the patient is constrained in a halo for instability.

If this is the case, the exposure will be more challenging but still possible.

Nasotracheal intubation opposite the side of the approach is desirable as it allows the jaw to be fully closed, offering the least inhibited exposure.

The pinna (earlobe) can be retracted forward and sewn anteriorly to allow better access to the styloid process and posterior ear area.

The entire cervical region and lower face is prepared and draped.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Anterior Approach (Smith-Robinson)

Incision and Superficial Dissection

A transverse incision placed in a skin crease is more cosmetic and suffices for accessing three or more disc levels in most instances.

A longitudinal incision, although less cosmetic, allows for a more extensile approach (C2-thoracic spine) and may be considered when three or more discs require access or if the patient has a very thick, muscular neck.

The incision is made using palpable anterior structures as a guide (ie, C3 hyoid bone, C4-C5 thyroid cartilage, C6 carotid tubercle, C7 cricoid cartilage) (TECH FIG 1A).

The preoperative lateral radiograph can also be used to determine roughly where to make the incision to allow optimal access to the desired disc(s).

The surgeon should try to make the incision such that it will be in line with the “line of sight” of the intended disc space (TECH FIG 1B).

Transverse incisions may extend from the anterior twothirds of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) to the midline.

Longer incisions and greater tissue mobilization facilitate multilevel procedures and will heal with a nearly imperceptible scar if placed within a natural skin crease.

Vertical incisions, if used, are placed along the medial border of the SCM.

The incision is continued through the subcutaneous fat to the platysma (TECH FIG 1C).

After dividing the platysma, blunt dissection with scissors undermines the edges of the platysma.

This allows for greater mobilization of the soft tissues, which is helpful in accessing multiple disc levels and getting enough exposure to place plates and screws.

Superficial veins crossing the field of dissection may need to be ligated to facilitate exposure (TECH FIG 1D).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree