Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the reliability and functional acceptability of the “Synthetic Autonomous Majordomo” (SAM) robotic aid system (a mobile Neobotix base equipped with a semi-automatic vision interface and a Manus robotic arm).

Materials and methods

An open, multicentre, controlled study. We included 29 tetraplegic patients (23 patients with spinal cord injuries, 3 with locked-in syndrome and 4 with other disorders; mean ± SD age: 37.83 ± 13.3) and 34 control participants (mean ± SD age: 32.44 ± 11.2). The reliability of the user interface was evaluated in three multi-step scenarios: selection of the room in which the object to be retrieved was located (in the presence or absence of visual control by the user), selection of the object to be retrieved, the grasping of the object itself and the robot’s return to the user with the object. A questionnaire was used to assess the robot’s user acceptability.

Results

The SAM system was stable and reliable: both patients and control participants experienced few failures when completing the various stages of the scenarios. The graphic interface was effective for selecting and grasping the object – even in the absence of visual control. Users and carers were generally satisfied with SAM, although only a quarter of patients said that they would consider using the robot in their activities of daily living.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluation de la fiabilité et de l’acceptabilité de l’usage d’un robot mobile d’assistance, Synthetic Autonomous Majordomo (SAM) composé d’une base mobile Néobotix avec bras télémanipulateur Manus, doté d’une interface de saisie automatique d’objet.

Patients et méthodes

Étude multicentrique ouverte contrôlée sous l’égide de l’association APPROCHE. Vingt-neuf patients tétraplégiques d’âge moyen 37,83 ± 13,3 : 23 blessés médullaires, 2 Locked In Syndrome, 4 autres pathologies. Trente-quatre sujets témoins d’âge moyen 32,44 ± 11,2. La fiabilité de l’interface graphique du système de commande a été évaluée à travers 3 scénarii comportant différentes étapes : désignation de la pièce où se trouve l’objet, déplacement de SAM vers l’objet, désignation de l’objet à saisir avec ou sans contrôle visuel, saisie automatique de l’objet, déclenchement du retour de SAM. L’usage du robot et son acceptabilité ont été évalués par un questionnaire.

Résultats

Le système est stable et fiable : il y a peu d’échec dans la réalisation des différentes étapes des scénarii aussi bien pour les patients que pour les témoins. L’interface graphique est efficace pour la désignation et la saisie de l’objet. SAM a été bien accueilli par tous les utilisateurs patients et thérapeutes. Mais seuls les patients envisageraient un transfert de l’utilisation du robot en vie quotidienne.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

People with a severe motor impairment require assistance with their activities of daily living. The prevalence of severe motor impairments is difficult to estimate, since many different diseases and conditions give rise to this type of handicap: spinal cord injury, neuromuscular diseases, demyelinising diseases, neurological paralysis, strokes, locked-in syndrome, etc. Affected patients have no other choice than to depend on human carers for their activities of daily living. The development of new technologies has given rise to assistive devices that provide patients with personal independence in some areas, such as moving around and controlling their immediate environment. According to Brochard et al., the degree of handicap is one of the factors that most strongly influences the need for (and acquisition of) assistive devices . It has also been emphasized that people with the need to compensate for severe motor impairment adopt computerized devices more readily than the general population does. Literature data evidence high levels of use and a fair level of satisfaction after the acquisition of technical aids – especially when the device is expensive or hard to obtain. Since 1979 (with the publication of the Spartacus project’s results on telemanipulator control by tetraplegic patients), research in the field of assistive robotics has focused on providing solutions for more complex acts (such as grasping objects) . We have detailed the history of assistive robotics in a previous article on the AVISO project . Although hi-tech assistive solutions have become increasingly sophisticated, few have been industrialized and bought by or supplied to patients. In fact, there are a number of technical, financial and human obstacles to more widespread use. In view of these difficulties, it is essential to expose prototypes to the end user as soon as possible and thus meet the latter’s criteria for efficiency and acceptability.

The European-Union-funded “Autonomic Networks for the Small Office and Home Office” (ANSO) project followed on from the AVISO project. Both projects have been run by the “Association pour la promotion des nouvelles technologies en faveur des personnes en perte d’autonomie” (APPROACH) network, in collaboration with French Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) . The AVISO study validated a graphic interface that enabled patients with motor handicap to control a robotic arm. The study results showed that interface was effective, with relatively few differences between patients and controls (given the severity of the handicap) and, above all, high levels of satisfaction. As an extension of the AVISO study, the ANSO project was designed to evaluate the device installed on a mobile base so that it could be used in a domestic environment (both close by the user and remotely). In the present study, patients and control participants evaluated the reliability of the SAM robot’s graphic interface in a domestic environment. Firstly, we checked that objects could be reliably grasped even when they were outside the patient’s and/or the camera’s field of view. Secondly, we compared performance levels in patients and controls. Thirdly, we evaluated the impact of the user’s familiarity with computer technology on the performance levels. Lastly, we evaluated the device’s use and acceptability via a questionnaire.

1.2

Materials and methods

1.2.1

Population

We performed an open, controlled study at two centres: the physical medicine and rehabilitation service at the Hopale Foundation in Berck-sur-Mer (France) and the Kerpape Rehabilitation Centre in Ploemeur (France) (both of which are institutional members of the APPROACH network). The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients aged 18 or over, normal cognitive function, and tetraplegia (with severe impairments of the arms limiting activities of daily living). The patients were being monitored on a regular basis by the physical medicine and rehabilitation services and were recruited into the study by telephone some time after their neurological injury. The patients’ results were compared with those of control participants (16 carers, together with 18 non-carers with no experience of robotics, technical aids or handicap).

1.2.2

Materials

The Synthetic Autonomous Majordomo (SAM) robot ( Fig. 1 ) consists of a mobile base (the MP470 from Neobotix, Heilbronn, Germany) and a Manus robot manipulator arm (Exact Dynamics, The Netherlands) equipped with an interface for automated object handling. Via an intuitive interface, SAM can move around in a known domestic environment, grasp an object and to take it to a designated location (i.e., back to the user or placed on a table). The robot’s sensors enable it to detect obstacles and choose the best path to its objective. It is also able to implement its own movement strategies.

1.2.2.1

Method

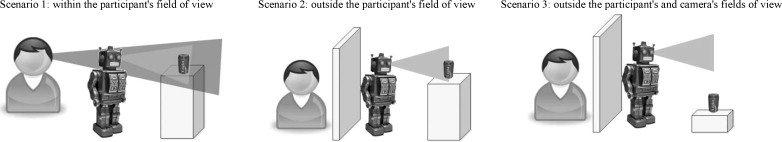

Use of the robot in a domestic environment (an apartment) was evaluated in three different scenarios ( Fig. 2 ). In the first scenario, the user had to instruct SAM to grasp an object situated in the same room. The object was set at a height that placed it directly within the camera’s field of view. In the second scenario, the user had to instruct SAM to go and retrieve an object located in a different room in the apartment, again at a height that placed it directly in the camera’s field of view. In the third scenario, the user had to ask SAM to go and retrieve an object located in a different room but placed outside the camera’s field of view. Each scenario comprised five steps:

- •

selection of the room in which the object was located;

- •

movement of the mobile base within or to the selected room;

- •

selection of the object to be retrieved;

- •

grasping of the object and;

- •

the mobile base’s return to its starting location.

For each user, the experimental procedure included a presentation of the apartment, preparation of the participant and the equipment (including choice of the control interface for pointing and validation and a presentation of the graphic interface), a practice session and the consecutive performance of the three scenarios. After the scenarios had been completed, the user rated the session qualitatively by completing a questionnaire. The control interfaces were personalized for the each participant’s functional impairments and corresponded to their usual interface for computer use or environmental control.

1.2.2.2

Evaluation criteria

We analyzed the room and object selection steps as a gauge of the quality of the graphic interface. These two steps were qualified in terms of the selection time (defined as the time between the task’s “start” command and the room/object selection click) and the number of failures (i.e., the number of attempts needed to accomplish the task minus one). We did not analyze the movement of the mobile base or the automated grasping movements. The evaluation criteria were as follows: the system’s ability to grasp an object within the user’s visual field or outside the user’s visual field (i.e. a comparison between scenarios 1 and 2), the system’s ability to grasp an object outside the user’s visual field or outside the camera’s field of view (i.e. a comparison between scenarios 2 and 3), the impact of the user’s familiarity with computerized equipment (novice/occasional/regular/expert user) and the impairment (patients vs. controls).

A qualitative questionnaire evaluated the participant’s satisfaction with technical aspects of the robot (the graphic interface, movement and control) and the participant’s overall satisfaction: learnability, confidence in the system, fatigue and acceptability of use in activities of daily living. Each question was scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not satisfied at all and 5 = very satisfied).

1.2.2.3

Statistical analysis

We used Student’s t test to compare mean values for the different scenarios and for patient vs. controls because we anticipated that the number of participants in each group would yield a normal data distribution. We used an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess the impact of the “experience of computer use” variable.

1.3

Results

Twenty-nine tetraplegic patients (mean ± SD age: 37.83 ± 13.3; 23 individuals with spinal cord injuries, 2 with post-stroke locked-in syndrome, one with arthrogryposis, one quadruple amputee, one with cerebral palsy and one with spinal muscular atrophy) were included in the study, as were 34 control participants (mean ± SD age: 32.44 ± 11.2; 16 carers, together with 18 non-carers with no experience of robotics, technical aids or handicap).

A mouse was used as the pointing interface by all the control participants and by 17% of the patients ( n = 5). The other interfaces used were (in decreasing frequency of use): a trackball ( n = 13 participants), IR tracking ( n = 5), a trackpad, an EasyMouse, a trackball plus stylus, a joystick and a numeric keypad. A mouse was used as the validation interface by all the control participants and by 17% of the patients ( n = 5). The other interfaces used were (in decreasing frequency of use) a trackball ( n = 12), a switch ( n = 5), a sip and puff switch ( n = 3), AutoClick, an EasyMouse, a trackball plus stylus and trackpad ( Fig. 3 ).

The data on patients and control participants are summarized in Table 1 .

| Patients ( n = 29) | Controls ( n = 34) | Patients vs. controls | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard deviation | Standard error of the mean | Mean | Standard deviation | Standard error of the mean | X (difference between the two means) | t test | P | < 0.05 = * | |

| Room selection time | ||||||||||

| Scenario 1 | 12.2710 | 11.24038 | 2.08729 | 5.5879 | 3.80460 | 0.65248 | −6.68309 | −3.259 | 0.002 | * |

| Scenario 2 | 14.7617 | 32.28269 | 5.99474 | 4.3844 | 3.26964 | 0.56074 | −10.37731 | −1.866 | 0.067 | NS |

| Scenario 3 | 5.1541 | 4.09603 | 0.76061 | 3.0253 | 3.60881 | 0.61891 | −2.12884 | −2.193 | 0.032 | * |

| Object selection-validation time | ||||||||||

| Scenario 1 | 102.2024 | 68.14146 | 12.65355 | 65.8697 | 23.96174 | 4.10940 | −36.33271 | −2.909 | 0.005 | * |

| Scenario 2 | 96.8821 | 35.18294 | 6.53331 | 59.2103 | 25.27448 | 4.33454 | −37.67177 | −4.930 | 0.000 | * |

| Scenario 3 | 139.3634 | 69.83106 | 12.96730 | 102.7403 | 48.50708 | 8.44400 | −36.62315 | −2.422 | 0.018 | * |

| Number of failures during selection of the room | ||||||||||

| Scenario 1 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.03 | 0.171 | 0.029 | 0.029 | 0.922 | 0.360 | NS |

| Scenario 2 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0 | – | – | nd |

| Scenario 3 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.03 | 0.171 | 0.029 | 0.029 | 0.922 | 0.360 | NS |

| Number of failures during selection-validation of the object | ||||||||||

| Scenario 1 | 0.03 | 0.186 | 0.034 | 0.06 | 0.239 | 0.041 | 0.024 | 0.446 | 0.657 | NS |

| Scenario 2 | 0.07 | 0.258 | 0.048 | 0.03 | 0.171 | 0.029 | −0.040 | −0.726 | 0.471 | NS |

| Scenario 3 | 0.17 | 0.602 | 0.112 | 0.12 | 0.327 | 0.056 | −0.055 | −0.458 | 0.649 | NS |

A comparison of scenarios 1 and 2 revealed the absence of a significant difference (for both patients and control participants) in the room/object selection and validation times and the number of failures. These results suggest that the graphic interface enabled the execution of command steps in both the presence and absence of visual control ( Table 2 ).

| Group | Scenarios compared | Parameter in the scenario | X (difference between the two means) | t test | Dep. value | Statistical significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Scenarios 1 and 2 | Room selection time | −2.49069 | −0.393 | 0.697 | NS |

| Object selection time | 5.32034 | 0.461 | 0.649 | NS | ||

| Number of room selection failures | 0 | – | – | nd | ||

| Number of object selection failures | −0.034 | −0.571 | 0.573 | NS | ||

| Scenarios 2 and 3 | Room selection time | 9.60759 | 1.656 | 0.109 | NS | |

| Object selection time | −42.48138 | – | 0.003 | P < 0.05 | ||

| Number of room selection failures | 0 | – | – | nd | ||

| Number of object selection failures | −0.103 | −0.828 | 0.415 | NS | ||

| Controls | Scenarios 1 and 2 | Room selection time | 1.20353 | 1.552 | 0.130 | NS |

| Object selection time | 6.65941 | 1.012 | 0.319 | NS | ||

| Number of room selection failures | 0.029 | 1.000 | 0.325 | NS | ||

| Number of object selection failures | 0.029 | 0.572 | 0.571 | NS | ||

| Scenarios 2 and 3 | Room selection time | 1.35912 | 1.701 | 0.098 | NS | |

| Object selection time | −43,12970 | –5.555 | 0.000 | P < 0.05 | ||

| Number of room selection failures | −0.029 | –1.000 | 0.325 | NS | ||

| Number of object selection failures | −0.088 | –1.358 | 0.184 | NS | ||

A comparison of scenarios 2 and 3 revealed a statistically significant difference (for both patients and control participants) in the object selection time in scenario 3 (in which the participant did not have visual control and the object was outside the camera’s field of view). The time spent searching for the object with the camera was longer in scenario 3. In contrast, there was no significant difference in the number of object selection failures; hence, the operation took longer but was performed effectively ( Table 2 ).

Experience of computer use had an influence on the speed of task performance by both patients and controls and in all scenarios ( Table 3 ).

| Group | Parameter in the scenario | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Room selection time | NS | NS | P < 0.05 |

| Object selection/validation time | NS | NS | NS | |

| Room selection failures | NS | NS | NS | |

| Object selection/validation failures | NS | NS | NS | |

| Controls | Room selection time | P < 0.05 | NS | NS |

| Object selection/validation time | NS | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| Room selection failures | NS | NS | NS | |

| Object selection/validation failures | P < 0.05 | NS | NS | |

A comparison of the results for patients and controls showed that patients took significantly longer to select the room and the object than the controls did (for room selection in scenarios 1 and 3 and for object selection in all three scenarios). In contrast, there were no significant patient vs. control differences in the number of failures ( Table 1 ).

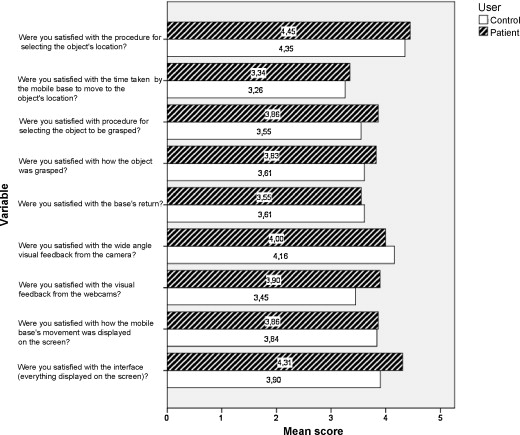

An analysis of the questionnaire data on the technical aspects ( Fig. 4 ) showed that controls and the patients had similar levels of satisfaction regarding the selection mode, the base’s speed of movement, object-grasping and the vision interface. Items concerning the graphic interface in general (selection mode and visual feedback from the camera) were given with higher scores than those concerning the robot’s performance, object-grasping and movement of the base.

Overall, the robot was found to be acceptable ( Fig. 5 ) by both patients and control participants. Both groups stated that it was easy to learn how to use SAM and that use was not fatiguing. However, patients were more confident than controls about using the robot to grasp fragile objects. In response to the question “Do you think that this robot could have practical uses at home?”, 60% of the patients and 40% of the controls answered “yes”. In response to the question “Do you think that use of SAM would reduce the amount of preparation or intervention by a carer at your home?”, 25% of the patients answered “yes” and most of the controls answered “no”. Likewise, a quarter of the patients (and none of the controls) stated that they would be ready to purchase the robot if it became commercially available (if cost was not an issue).

1.4

Discussion

To date, most of the published clinical evaluations of assistive robotics have been performed with robotised arms attached to a fixed base (i.e., the MASTER, RAIDMASTER and AVISO projects) or to the user’s electric wheelchair (i.e., the MANUS project) . The AVISO project enabled us to validate a graphic interface for the automated manipulation of objects. Use of a mobile base has been described in the ARPH project . The ANSO project combined these two aspects: the robot can move around freely in a known apartment, without being restricted to a working environment under visual control, and enables the automation of certain tasks, such as moving from the starting point to a preselected point in the apartment and the automatic grasping of objects after selection via the graphic interface. The webcams placed on the robot’s gripper arm enables the operator to view the object to be grasped. The grasping task is simplified by use of an automatic grasping system. The observed difference between patients and controls in terms of selection is probably related to the user interfaces; patients were slower. This underlines the importance of automating certain manipulation steps. However, the low failure rate observed with both patients and controls attests to the system’s reliability.

We noted a number of technical limitations during the present study: the infrared and laser sensors for obstacle detection did not locate all the objects present – particularly if the latter were less than 14 cm in height (i.e., below the level of the laser beam). When moving, the base could avoid obstacles but did not correctly evaluate its own volume. The base’s small wheels prevent it from crossing minor obstacles (a door threshold or the edge of a carpet). Some objects could not be grasped securely with the two-finger gripper and the robot could not pick up objects off the floor.

Despite the availability of financial assistance in some circumstances, cost is an obstacle to the acquisition of hi-tech assistance devices. Brochard et al.’s study of a population of tetraplegic patients showed that 74% of the participants did not acquire the technical aid because of the absence of financial assistance; 23% cited a lack of information and 21% had trouble obtaining a trial of the equipment. Furthermore, one must not underestimate psychosocial and cultural obstacles to the widespread uptake of this type of technology. This is why the APPROACH network has long been evaluating the acceptability and psychosocial impact of prototype robotic assistance devices (notably through the MASTER and AVISO projects). SAM constitutes a significant advance in assistive systems, by combining a mobile base, independent operation and assistance with grasping objects. The results of the user satisfaction questionnaire showed that the patients are more inclined than able-bodied participants to acquire this type of device. In contrast to the controls, the patients considered that the robot could have practical uses and could modify third-party care activities. These differences of opinion emphasize the importance of evaluating the psychosocial dimension with methodologies adapted from the social sciences. .

1.5

Conclusion

This clinical trial of a prototype assistive robot enabled us to validate certain technical aspects and (in particular) its graphic interface for grasping remote objects outside the patient’s field of view – an essential functional objective for people with reduced mobility. Use of the device in a real-life situation showed that patients with functional impairments had a more favourable opinion of the robot and would be ready to trust it in their activities of daily living. These findings underline the importance of:

- •

validating prototypes with the end user early on in the development process;

- •

gathering information on needs and uses and;

- •

performing pilot clinical studies.

Close collaboration between researchers and clinical networks (such as APPROACH) is a prerequisite for the initiation of industrial-scale developments.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Les personnes présentant une déficience motrice sévère ont besoin d’assistance pour les actes courants de la vie quotidienne. Le nombre de personnes concernées est difficile à estimer, les pathologies à l’origine de ce type de handicap étant très diverses : traumatismes vertébromédullaires, pathologies neuromusculaires, pathologie démyélinisante, paralysie cérébrale, accidents vasculaires cérébraux responsable de locked in syndrome… Ces patients sont dépendants pour les actes de la vie quotidienne et n’ont d’autre choix que le recours à une assistance humaine. Le développement des nouvelles technologies donne l’accès à des aide techniques permettant une autonomie dans certains actes tels que les déplacements et le contrôle de l’environnement. D’après Brochard et al., l’un des facteurs influençant les acquisitions et les besoins de matériel est l’importance du handicap . Il était également souligné l’utilisation plus importante de l’outil informatique que dans la population générale montrant une meilleure capacité des personnes présentant un handicap moteur sévère à accueillir les technologies dans la vie quotidienne en vue de la compensation de leurs déficiences. Les études montrent un taux d’utilisation très élevé de même qu’un bon niveau de satisfaction après acquisition de l’aide technique surtout lorsque leur acquisition n’est pas aisée . Depuis une trentaine d’années, la recherche dans le domaine de la robotique d’assistance tente d’apporter des solutions pour des actes plus complexes comme la saisie d’objets avec dès 1979 la publication de l’expérimentation d’un robot manipulateur auprès de patients tétraplégiques dans le projet Spartacus . Nous ne revenons pas ici sur l’historique de la robotique d’assistance que nous avons pu détailler dans notre précédent article sur le projet AVISO . Les réponses technologiques n’ont cessé de progresser, mais très peu sont allées jusqu’à la phase de l’industrialisation et leur diffusion auprès de patients est restée confidentielle. Les verrous à cette diffusion sont multiples : techniques, financiers, humains. Compte tenu de ces difficultés, il apparaît essentiel de pouvoir confronter les prototypes à l’utilisateur final dès les premières phases de développement afin d’être au plus proche de leurs besoins tant en termes d’efficience que d’acceptabilité.

Le projet européen ANSO-Autonomic Networks for SOHO (Small Office and Home Office) fait suite au projet AVISO. Ces projets ont été conduits sous l’égide de l’association APPROCHE (Association pour la promotion des nouvelles technologies en faveur des personnes en perte d’autonomie) en partenariat avec le CEA-List (Commissariat à l’Énergie Atomique) . L’étude AVISO avait permis de valider l’efficacité d’une interface graphique de commande d’un bras manipulateur robotisé auprès de patients présentant une déficience motrice. Les résultats montraient une bonne efficacité de l’interface avec des différences entre patients et témoins minimes compte tenu de l’importance du handicap et surtout un haut niveau de satisfaction. Dans la continuité de l’étude AVISO, l’objectif du projet ANSO était d’évaluer le dispositif installé sur une base mobile permettant l’utilisation en environnement domestique à proximité ou à distance de l’opérateur. L’étude évalue la fiabilité de l’interface graphique du robot en environnement domestique par des patients et des témoins. Dans un premier temps, nous avons vérifié si les opérations de saisie d’objet à distance sont fiables même pour des objets situés en dehors du champ visuel du patient et/ou de la caméra. Dans un deuxième temps, nous avons comparé les performances des patients et des témoins. Ensuite, nous avons évalué l’impact de l’expérience en informatique sur les résultats. Enfin, l’usage du robot et son acceptabilité ont été évalués par un questionnaire.

2.2

Matériel et méthode

2.2.1

Population

Nous avons conduit une étude ouverte contrôlée bicentrique dans le service de médecine physique et de réadaptation du groupe Hopale de Berck-sur-mer et du CMRRF de Kerpape à Ploemeur, établissements membres de l’association APPROCHE. Les critères d’inclusion étaient : patients âgés de plus de 18 ans, avec des fonctions cognitives intègres, tétraplégiques avec des déficiences sévères des membres supérieurs rendant compte de limitations d’activités dans la vie quotidienne. Les patients suivis régulièrement par les services de médecine physique et de réadaptation et à distance de leur événement neurologique ont été recrutés par téléphone. Les résultats obtenus étaient comparés à ceux de sujets témoins : 16 soignants et 18 sujets non soignants n’ayant aucune expérience en robotique, ni dans les aides techniques et le handicap.

2.2.2

Matériel

SAM-synthetic Autonomous Majordomo ( Fig. 1 ) est composé d’une base mobile MP470 (Néobotix) et d’un bras télémanipulateur Manus (Exact Dynamics, Neederland), doté d’une interface de saisie automatique d’objet. Piloté par l’intermédiaire d’une interface intuitive, SAM est capable de se déplacer dans un environnement domestique connu, de saisir un objet et de le ramener à l’endroit désiré (auprès de la personne, sur une table). Grâce à ses capteurs, la base mobile est capable de détecter un obstacle et de choisir la meilleure trajectoire pour atteindre son but. Il est également capable de mettre en place ses propres stratégies de déplacement.