Ankle Fracture Malunion and Late Syndesmosis Reconstruction

Gregory A. Lundeen

Lex A. Simpson

Timothy J. Bray

Fracture and soft tissue injuries to the ankle are among the most common musculoskeletal injuries (1). Improvements in our understanding of the mechanism of injury and surgical techniques for anatomic repair have improved the outcomes. These techniques focus on preservation of the soft tissue envelope and distraction methods to regain fibular length and orientation. However, ankle fractures remain difficult in cases with comminuted fractures and high-energy injuries where anatomic orientation may not be possible and also may involve the tibiofibular ligament complex (the syndesmosis). It is well understood that anatomic reduction of ankle fractures is imperative to decrease the potential for posttraumatic arthritis and altered ankle mechanics.

The orientation of the fibula dictates the ankle mortise anatomy and the position of the talus under the tibial plafond. Malalignment of the mortise is characterized by fibular shortening, lateral shift, and/or malrotation leading to displacement of the talus under the tibial plafond. This displacement of the talus and the mortise can be defined by the talus lateralized relative to the medial malleolus increasing the medial clear space, the weight-bearing surface of the talus angulated to the tibial plafond, or the fibula lateralized from the talus as in a syndesmosis disruption. The distal tibiofibular joint is a relatively stable joint as long as the fibula is positioned anatomically in the incisura of the distal tibia. The ankle is a very precise joint where room for error is measured within a couple of millimeters. When the mortise is compromised, models under physiologic loads have demonstrated contact pressures on the tibiotalar joint are increased in the mid-lateral and posterior-lateral compartments. If left untreated, the risk of pain and degenerative changes are significant. The goal of surgical correction for fibular malalignment is to restore this sensitive weight-bearing area to normal anatomic relationships (2, 3, 4, 5 and 6). Because small abnormalities can result in larger long-term consequences, the surgeon evaluating these patients should do so with a critical eye.

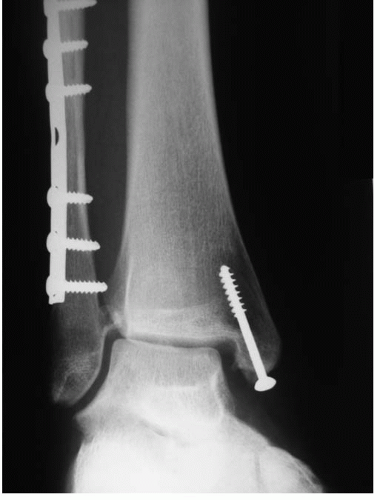

There are many reasons a patient may present late with a nonanatomic ankle mortise. It is most common that the fibula was not anatomically placed during the initial open reduction and internal fixation, leaving the fibula to heal shortened, malrotated, and/or angulated. It is also possible that the patient with an ankle malunion was never treated with surgery or did not seek medical attention. Finally, there are those patients who had a Maisonneuve fracture or purely soft tissue disruption to the syndesmosis with widening of the distal tibiofibular joint after internal fixation was removed or broken. This is oftentimes a result of the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL) becoming impinged between the tibia and fibula, which does not allow for satisfactory healing resulting in persistent instability.

Abnormalities of talar position within the ankle mortise are typically visible on plain film radiographs. Using the involved ankle radiographs, the surgeon can measure widening of the medial joint

space, talar tilt, and fibular shortening compared with the opposite, normal ankle radiographs. Because rotational malalignment of the distal fibula is more difficult to visualize, it can be assessed with computed tomography (CT) scanning. With the absence of metal implants at the joint, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can have the added advantage of evaluating the ankle ligaments and joint cartilage assessment. This may be helpful when discussing surgical outcomes during preoperative planning.

space, talar tilt, and fibular shortening compared with the opposite, normal ankle radiographs. Because rotational malalignment of the distal fibula is more difficult to visualize, it can be assessed with computed tomography (CT) scanning. With the absence of metal implants at the joint, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can have the added advantage of evaluating the ankle ligaments and joint cartilage assessment. This may be helpful when discussing surgical outcomes during preoperative planning.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

In addition to determining the degree of pain and disability associated with the ankle malalignment, the severity of degenerative joint disease must be assessed. If only mild or moderate, the surgeon can proceed with realignment based on the experience that symptoms will often improve and the progression of posttraumatic arthritis can be slowed or stopped. If, however, there is advanced arthritis, then realignment alone may not provide long-term pain relief to the patient. The patient may benefit from a realignment procedure in conjunction with an ankle distraction arthroplasty. It should also be considered in the patient who may be a candidate for a total ankle arthroplasty (TAA) in the future as an incongruent joint is a relative contraindication for TAA. The patient may also be best served with a well-aligned ankle arthrodesis. The appropriate direction to proceed in the patient with significant arthritis and ankle malposition is based upon patient factors such as age, health, and activity level and surgeon experience and preference.

The involved extremity is assessed for acceptable vascularity and soft tissue viability. Infection is always possible and must be excluded with appropriate testing. Peripheral neuropathy caused by diabetes mellitus or other disorders are relative contraindications, and one should proceed with caution with operative treatment. The physician must ensure that the patient is of appropriate age, is in reasonably good health, and understands that complete relief of symptoms may not ensue. The surgeon should explain the possible need for subsequent procedures, such as ankle arthrodesis, to treat symptoms not resolved by the initial realignment operation.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Preoperative planning begins with the history and physical examination, attempting to confirm the ankle as the source of symptoms and eliminating other causes of lower extremity pain. Pain and tenderness should be localized to a specific area and correlated, if possible, to documented areas of malalignment. If uncertain, differential injections with anesthetic agents such as lidocaine can be helpful. The examiner records the pain level, gait, activity restrictions, and range of motion of the ankle, subtalar, and transverse tarsal joints. The same evaluation technique is used in the late followup period to assess the overall results and presence or absence of late degenerative change. Several foot and ankle functional scoring systems are available for quantitating the results.

The surgeon scrutinizes weight-bearing plain film radiographs, including anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and mortise (internally rotated 20°) views of the involved and uninvolved ankles. Where applicable, AP and lateral views of the tibia and fibula may be beneficial, particularly in those patients with Maisonneuve or high fibular shaft fractures. The mortise view demonstrates at least five characteristics between the normal and involved ankle.

The first characteristic is an equidistant and parallel joint space with no medial widening. Lateral displacement of the talus within the mortise due to fibular shortening or medial tissue interposition is noted. Any increase in medial widening, even subtle, compared with the joint space laterally is considered abnormal. The reported upper limit of normal is 4 mm (Fig. 32.1).

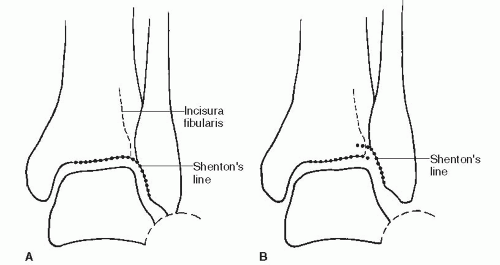

The second characteristic demonstrates a Shenton line of the ankle. The dense subchondral bone supporting the bone of the tibia creates a radiographic line that can be followed over the syndesmotic space to the fibula, where a small spike points to the tibial subchondral bone (Fig. 32.2).

The third characteristic is an unbroken curve between the lateral part of the articular surface of the talar lateral process and the distal fibular recess (Fig. 32.2).

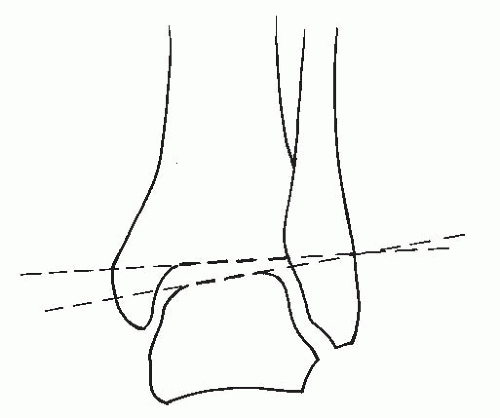

The fourth characteristic is talar tilt. This is a measured by lines drawn along the dome surface of the talus and the tibial plafond. In neutral, weight-bearing stress and the ankle at 90°, these lines should be parallel or within three degrees of parallel (Fig. 32.3).

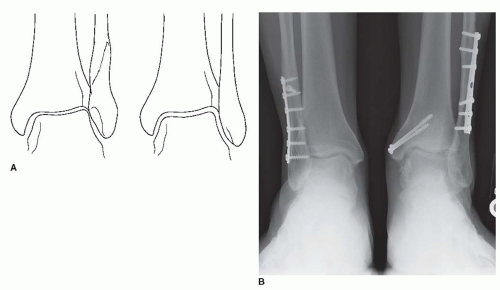

The final radiographic consideration on the mortise view is to evaluate the degree of malrotation. This can be assessed by evaluating the origin of the calcaneofibular ligament, which is the radiographic fossa at the distal anterior aspect of the lateral malleolus. Malrotation is noted when the radiographic shadows of this area are asymmetric (Fig. 32.4).

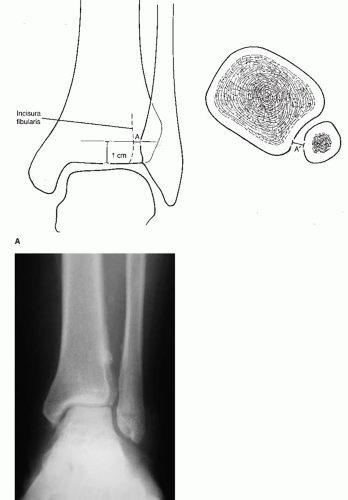

The surgeon should look for evidence of abnormal seating of the fibula in the incisura fibularis of the tibia representing the tibiofibular or syndesmotic interval. Two parameters involving this tibiofibular

interval are diminished overlap of the distal fibula and anterior tibial tubercle and an increase in the tibiofibular clear space. Of these, the latter appears to be more reliable, with the normal width being less than 6 mm as measured 1 cm above the plafond (Fig. 32.5). Because the clear space represents the posterior aspect of the tibiofibular interval, its width can also vary with rotational deformity of the fibula. Internal fibular rotation, for instance, may contribute to an increase in this distance, and external fibular rotation is possible in association with this interval appearing normal or diminished.

interval are diminished overlap of the distal fibula and anterior tibial tubercle and an increase in the tibiofibular clear space. Of these, the latter appears to be more reliable, with the normal width being less than 6 mm as measured 1 cm above the plafond (Fig. 32.5). Because the clear space represents the posterior aspect of the tibiofibular interval, its width can also vary with rotational deformity of the fibula. Internal fibular rotation, for instance, may contribute to an increase in this distance, and external fibular rotation is possible in association with this interval appearing normal or diminished.

FIGURE 32.1 Medial joint space widening is associated with a lateral shift of the talus and syndesmosis instability. |

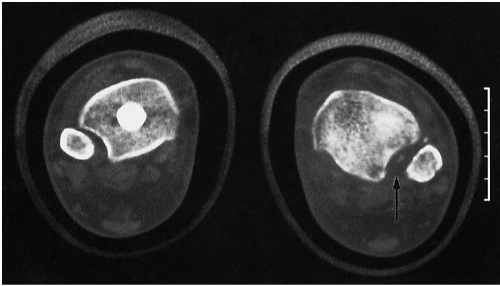

Although plain film radiographs usually provide useful information about the nature of the malunion, the definitive study is the CT scan or MRI, or both. Axial cuts across the tibiofibular interval and ankle mortise with comparison views of the normal ankle can accurately determine the amount of talar shift as well as the position of the fibula relative to the tibia. Malrotation of the fibula with internal and external rotation being encountered can be assessed by noting the width of the tibiofibular interval at the anterior and posterior aspects of the syndesmosis. External rotation of the relatively oval-shaped fibula manifests as asymmetric widening anteriorly and as versus internal rotation, which appears as asymmetric widening posteriorly (Fig. 32.6). Sagittal and coronal cuts are helpful for assessing the posterior malleolus component to the fracture if present as well as defining the malunion of the fibula in degrees of varus, valgus, and angulation with the apex anterior or posterior (Fig. 32.7). Anatomically, the fibula is a straight bone on AP and lateral views. CT can also be helpful to assess bony or soft tissue debris that may interfere with satisfactory reduction of the tibiofibular interval (Fig. 32.8). Finally, three-dimensional reconstructions may be helpful as well to understand the malunion to develop the correct preoperative surgical plan. It is of the utmost importance that the surgeon completely understands the deformity and the mechanism of injury before performing any surgical realignment procedures.