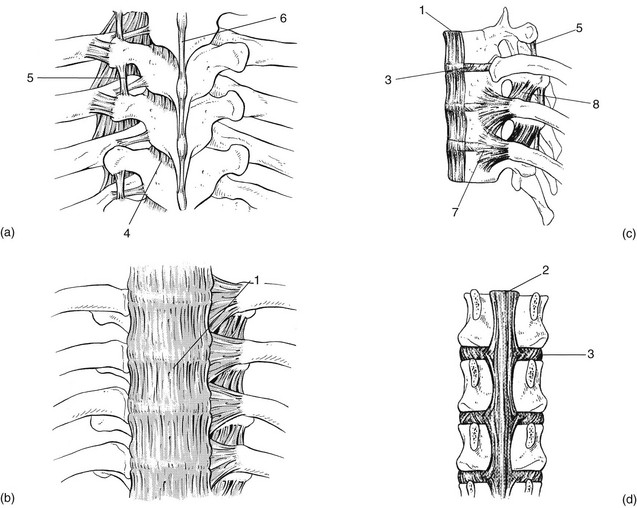

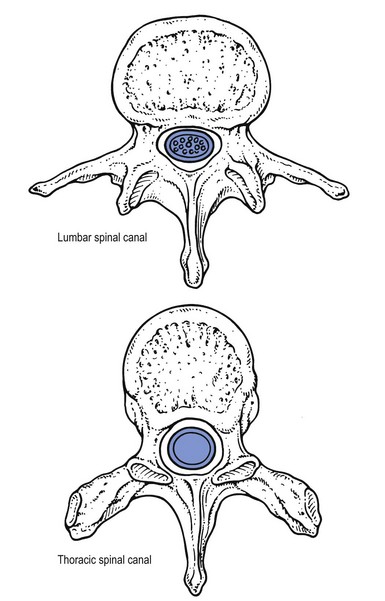

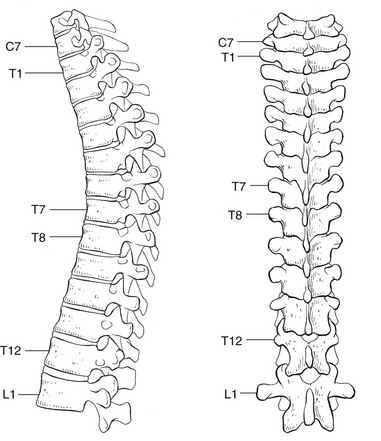

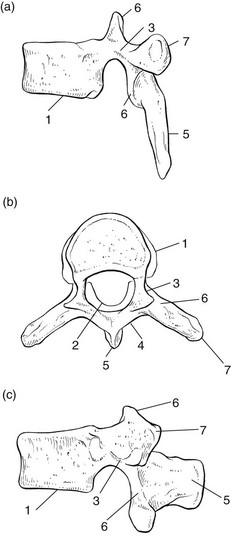

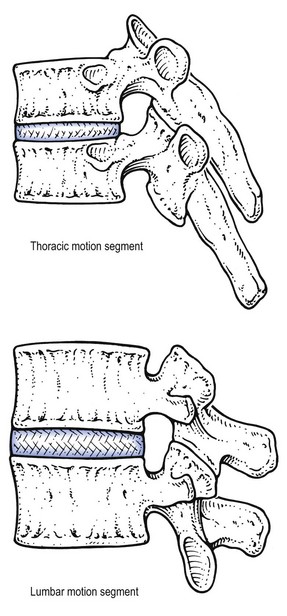

The thoracic spine has a primary dorsal convexity (Fig. 1) associated with intrauterine life – a phylogenetic kyphosis – whereas the cervical and lumbar spine have a compensatory lordosis. The 12 thoracic vertebrae are intermediate in size between those in the cervical and lumbar regions. They are composed of a vertebral body – a cylindrical ventral mass of bone – continuing posteriorly into a vertebral arch (Fig. 2). The typical thoracic vertebral body is heart-shaped in cross-section and has on each of its lateral aspects a superior and inferior costal facet for articulations with the ribs (costovertebral joints). The arch is constructed out of two pedicles and two short laminae, the latter uniting posteriorly to form the spinous process. Laminae and spinous processes lie obliquely covering each other like the tiles of a roof, so protecting the posterior cord posteriorly. The pedicles carry the articular and transverse processes. The oval intervertebral foramina are located behind the vertebral bodies and between the pedicles of the adjacent vertebrae and contain the segmental nerve roots. In the thoracic spine, these are situated mainly behind the inferoposterior aspect of the upper vertebral body and not just behind the disc. This makes a nerve root compression by a posterolateral displacement less likely at the thoracic level, whereas at the lumbar level nerve root compressions by posterolateral disc protrusions are quite common (Fig. 3, see Standring, Fig. 42.27). A fibrocartilaginous disc forms the articulation between two vertebral bodies. The anatomy and behaviour of discs are discussed in Chapter 31, Applied anatomy of the lumbar spine. However, it is worth noting here that thoracic discs are narrower and flatter than those in the cervical and lumbar spine. Disc size gradually increases from superior to inferior. The nucleus is rather small in the thorax. Therefore protrusions are usually of the annular type, and a nuclear protrusion is very rare in the thoracic spine. The longitudinal ligaments run anteriorly and posteriorly on the vertebral bodies (Fig. 4, see Standring, Fig. 54.10). The anterior ligament covers the whole of the vertebral bodies’ anterior aspect and some of their lateral aspect. It is firmly connected to the periosteum but only loosely to the discs. The posterior longitudinal ligament is strongly developed at the thoracic level and is wider than in the lumbar region, although it covers only a part of the posterior aspect of each vertebral body. It has some lateral expansions, which are firmly attached to the discs. The ligamentum flavum, interposed between the laminae, extends laterally as far as the medial part of the inferior articular process. At each level the ligamentum flavum has lateral extensions to both sides to form the capsules of the facet joints (see Standring, Fig. 42.42). The transverse processes are connected to each other by the intertransverse ligaments. The supra- and interspinal ligaments bridge the gap between the spinous processes. The spinal canal is formed by the vertebral foraminae of the successive vertebrae, the posterior aspects of the discs, the posterior longitudinal ligament, the ligamenta flava and the anterior capsules of the facet joints. In contrast to the cervical and lumbar regions, where the canal is triangular in cross-section and offers a large lateral extension to the nerve roots, the thoracic spinal canal is small and circular. It can be divided into three zones: the upper (T1–T3), and lower (T10–T12) zones are transitional, respectively, the cervical and the thoracic spine, and the thoracic and the lumbar spine. Between these is the mid-thoracic zone (T4–T9), where the spinal canal is at its narrowest (Fig. 5). The spinal canal contains the dural tube, within which are the spinal cord, the spinal nerves and the epidural tissue (see Standring, Fig. 43.3).

Applied anatomy of the thorax and abdomen

The thoracic spine

The vertebra

The intervertebral disc

The ligaments

Content of the spinal canal

anatomy of the thorax and abdomen

levels.

levels.