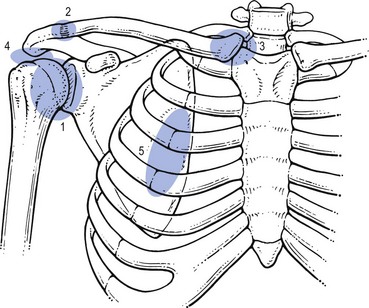

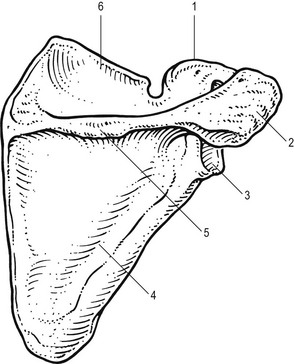

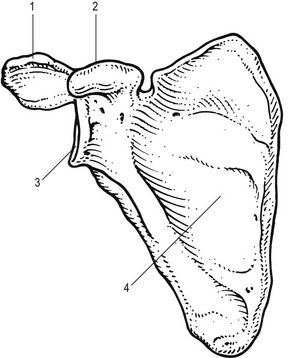

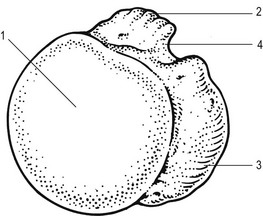

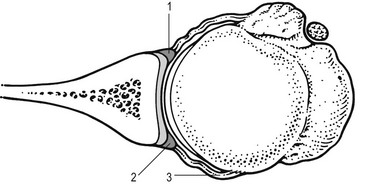

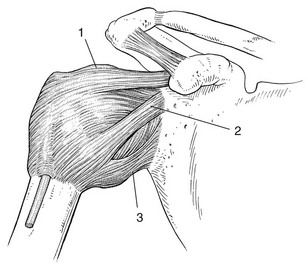

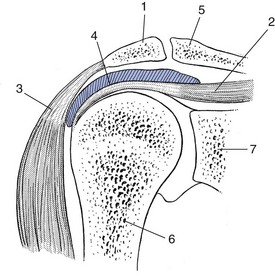

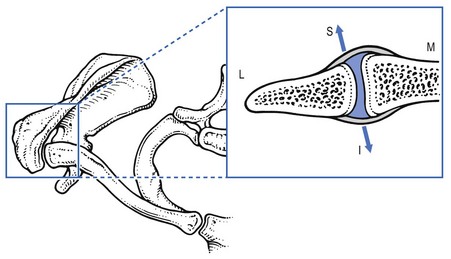

The main function of the joints of the shoulder girdle (Fig. 1) is to move the arm and hand into almost any position in relation to the body. As a consequence the shoulder joint is highly mobile, where stability takes second place to mobility, as is evident from the shape of the osseous structures: a large humeral head lying on an almost flat scapular surface. Stability is provided mainly by ligaments, tendons and muscles; the bones and capsule are of secondary importance. The function of the shoulder girdle requires an optimal and integrated motion of several joints. In fact five ‘joints’ of importance to ‘shoulder’ function can be distinguished:1 • The acromioclavicular joint (2) • The sternoclavicular joint (3) • The subacromial joint or subacromial gliding mechanism (4): the space between the coracoacromial roof and the humeral head, including both tubercles. This is the location of the deep portion of the subdeltoid bursa • The scapulothoracic gliding mechanism (5): this functional joint is formed by the anterior aspect of the scapula gliding on the posterior thoracic wall. Optimal mobility also requires an intact neurological and muscular system. The scapula is a thin sheet of bone that functions mainly as a site of muscle attachment (Figs 2–3, see Putz, Figs. 286, 287, 288). Its medial border is parallel to the spine, the lateral and superior borders are oblique. It has a superior, a lateral and an inferior angle. The inferior angle corresponds to the interspinal level between the spinous processes of T7 and T8. When the arm is hanging down the side with its anterior aspect facing the body, the greater tuberosity lies laterally and the lesser tuberosity anteriorly. They are separated from each other by the bicipital sulcus (Fig. 4). The glenohumeral joint (Fig. 5) is a ball-and-socket between humeral head and glenoid fossa. There is a remarkable geometrical relationship between glenoid and head which is responsible for the considerable mobility of the joint but is also an important predisposing factor to glenohumeral instability. First, the large spherical head of the humerus articulates against the small shallow glenoid fossa of the scapula (only 25–30% of the humeral head is covered by the glenoid surface). Second, the bony surfaces of the joint are largely incongruent (flat glenoid and round humerus). However, the congruence is greatly restored by the difference in cartilage thickness: glenoid cartilage is found to be the thickest at the periphery and thinnest centrally, whereas humeral articular cartilage is thickest centrally and thinnest peripherally. This leads to a uniform contact between humeral head and glenoid surface throughout shoulder motion. The labrum is a fibrous structure that forms a ring around the periphery of the glenoid (see Putz, Fig. 298). It acts as an anchor point for the capsuloligamentous structures and for the long head of the biceps. It further contributes to stability of the joint by increasing the depth of the glenoid socket, enlarging the surface area and acting as a load-bearing structure for the humeral head. At the anterior portion of the capsule three local reinforcements are present: the superior, medial and inferior glenohumeral ligaments (Fig. 6). These contribute, together with the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor muscles, to the stability of the joint. The suprahumeral gliding mechanism consists of the coracoacromial arch (see below) on one side and the proximal part of the humerus, covered by the rotator cuff and the biceps tendon on the other. Both parts are separated by the subacromial bursa that acts as a joint space (Fig. 7). Investigators point to the importance of contact and load transfer between the rotator cuff and the coracoacromial arch in the function of the normal shoulder. Normally there is no communication between the bursa and the glenohumeral joint space but it may be established by rupture of the rotator cuff. The acromioclavicular joint (Fig. 8) is the only articulation between the clavicle and the scapula. It contains a disc which usually has a large perforation in its centre. The capsule is thicker on its superior, anterior and posterior surfaces than on the inferior surface. The anteroposterior stability of the acromioclavicular joint is controlled by the acromioclavicular ligaments and the vertical stability is controlled by coracoclavicular ligaments (conoid and trapezoid). The only osseous connection between the skeleton of the trunk and the upper limb is formed by the clavicle. Its medial end lies in contact with the superolateral angle of the sternal manubrium and with the medial part of the cartilage of the first rib to form the sternoclavicular joint (Fig. 9, see Putz, Fig. 285). In both the vertical and anteroposterior dimensions, the clavicular portion is larger than the opposing manubrium and extends superiorly and posteriorly relative to the sternum. The prominence of the clavicle enables its palpation. The sternoclavicular joint is mobile along all axes and almost every movement of the scapula and the arm is associated with some movement at this joint.

Applied anatomy of the shoulder

Introduction

Bones

Scapula

Humerus

Joints and intracapsular ligaments

Glenohumeral joint

Subacromial space

Acromioclavicular joint

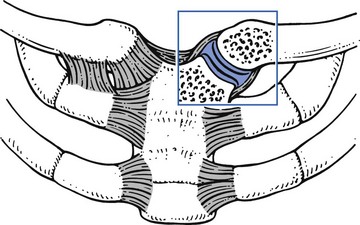

Sternoclavicular joint

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine