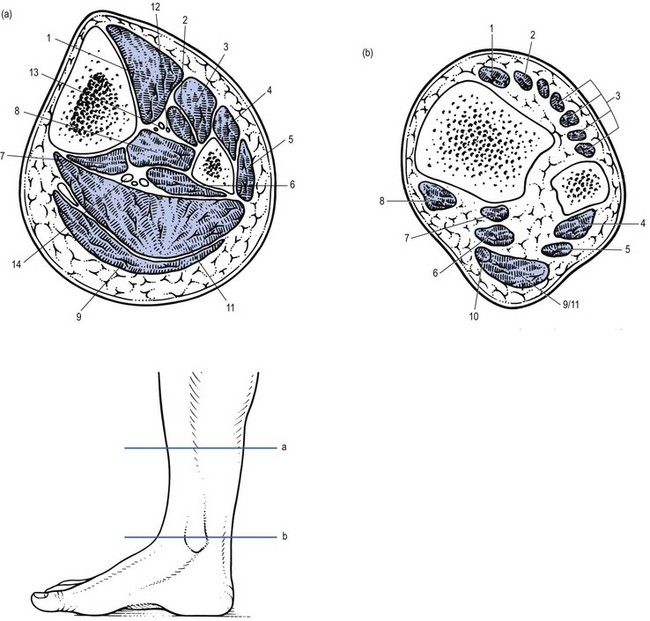

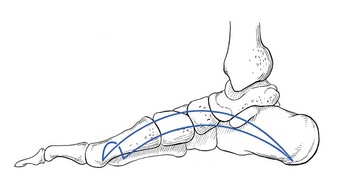

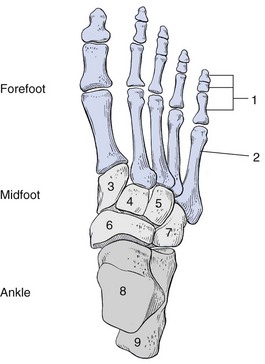

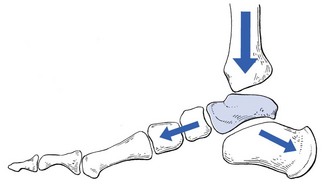

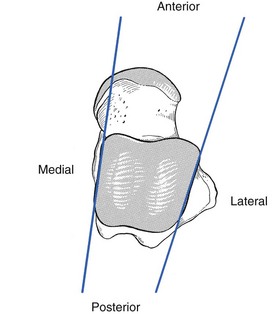

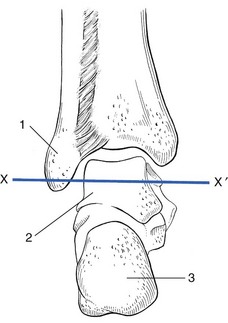

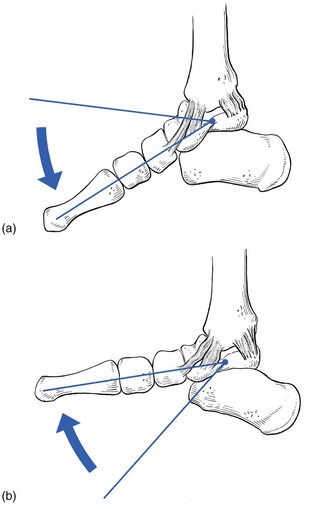

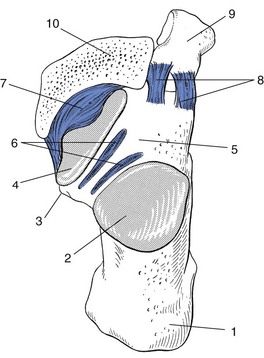

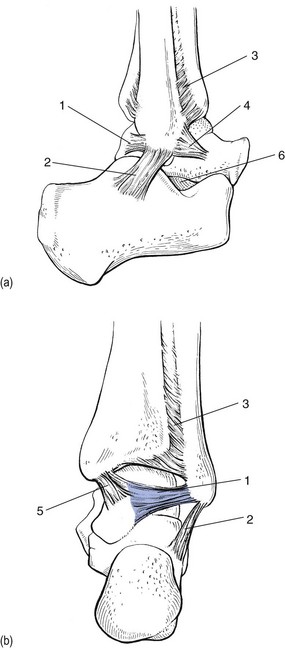

• Plantiflexion–dorsiflexion indicate movement at the ankle. Plantiflexion is movement downwards towards the ground, and dorsiflexion upwards towards the tibia. There is also a plantiflexion–dorsiflexion movement at the midtarsal joint. • Varus–valgus: these movements occur at the subtalar joint. In valgus, the calcaneus is rotated outwards on the talus; in varus, the calcaneus is rotated inwards on the talus. • Abduction–adduction: these take place at the midtarsal joints. Abduction moves the forefoot laterally and adduction moves the forefoot medially on the midfoot. • Pronation–supination are also movements at the midtarsal joints. In pronation, the forefoot is rotated big toe downwards and little toe upwards. In supination, the reverse happens: the big toe rotates upwards and the little toe downwards. Sometimes the terms internal rotation and external rotation are used to indicate supination or pronation. • Inversion–eversion: these are combinations of three movements. In inversion, the varus movement at the subtalar joint is combined with an adduction and supination movement at the midtarsal joint. During eversion, a valgus movement at the subtalar joint is combined with an abduction and pronation movement at the midtarsal joint. The muscles of the anterolateral compartment are the tibialis anterior, the extensor hallucis and the extensor digitorum, which are all dorsiflexors. The tibialis anterior, however, is also an invertor. The muscles lie in a strong osteofibrous envelope, consisting of tibia, fibula, interosseous membrane and superficial fascia. The anterior tibial artery (Fig. 1) is located at the anterior surface of the interosseous membrane. It supplies the muscles of the anterior compartment and continues at the dorsum of the foot as the dorsalis pedis artery. The nerve supply of the anterior compartment is from the deep peroneal nerve, a branch of the common peroneal nerve. The 26 bones of the foot create an architectural vault, supported by three arches and resting on the ground at three points, which lie at the corners of an equilateral triangle (Fig. 2). Ligaments bind the bones to provide the static stability of the foot. The dynamic stability of the vault is achieved by the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles. Three functional segments can be distinguished: forefoot, midfoot and ankle (Fig. 3). Each has its particular functions and specific disorders (see Standring, Fig. 84.8A). The posterior segment (ankle) is the connection between foot and leg. It lies directly under the tibia and fibula and is connected to them by strong ligaments. This segment contains the talus (in the mortice between the fibula and the tibia) and the calcaneus. The talus is the mechanical keystone at the ankle (Fig. 4). It distributes the body weight backwards towards the heel and forwards towards the midfoot (medial arch of the plantar vault). The talus has no muscular insertions but is entirely covered by articular surfaces and ligamentous reinforcements. It is also crossed by the tendons of the extrinsic muscles of the foot. The superior surface and the two sides of the body of the talus are gripped between fibular and tibial malleoli, forming the ankle mortice (see Standring, Fig. 84.16). Stability of this tibiofibular mortice is provided by the anterior and posterior tibiofibular ligaments and the interosseous ligament. Because the body of the talus is wedge shaped, with the wider portion anterior, no varus–valgus movement will be possible with an ankle held in dorsiflexion, unless the malleoli or the tibiofibular ligaments are damaged (Fig. 5). The normal movement of the ankle joint is plantiflexion–dorsiflexion, through an axis that passes transversely through the body of the talus. The lateral end of this axis goes through the lateral malleolus (Fig. 6). Hence, a normal plantiflexion–dorsiflexion movement does not influence the tightness of the calcaneofibular ligament. At the medial end, however, the axis is placed under the tip of the medial malleolus and thus under the malleolar point of attachment of the medial ligaments. Here, the posterior fibres of the deltoid ligament will become taut on dorsiflexion and the anterior fibres on plantiflexion (Fig. 7). The subtalar or talocalcaneal joint consists of two separate parts, divided by the tarsal canal (Fig. 8), which is funnel shaped with the wide portion at its lateral end. The lateral end of the canal is easily palpated in front of the fibular malleolus between talus and calcaneus, especially when the foot is inverted. The canal runs posteromedially, to have its medial opening just behind and above the sustentaculum tali. In the canal a strong ligament, the interosseous talocalcaneal ligament, binds the two bones (see Standring, Fig. 84.15). The anterior talofibular ligament is a triangular structure, its base attached to the anterior margin of the fibular malleolus and the smaller insertion at the neck of the talus (Fig. 9), just behind the mouth of the sinus tarsi.

Applied anatomy of the lower leg, ankle and foot

Definitions

The leg

Anterolateral compartment

The ankle and foot

The posterior segment

Ankle joint

Subtalar joint

Ligaments of ankle and subtalar joints (see Standring, Fig. 84.13)

Lateral ligaments

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree